Abstract

Bacillus Calmette-Guërin (BCG) has been traditionally used as a vaccine against tuberculosis. Further, intravesical administration of BCG has been shown to be effective in treating bladder cancer. Although BCG contains a live attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis, complications such as M. bovis BCG infection caused by BCG administration are extremely rare. Here, we report a case of BCG infection occurring after intravesical BCG therapy. A 67-yr-old man presented with azotemia and weight loss. He had been diagnosed with bladder cancer 4 yr back, and had undergone transurethral resection of the bladder tumor and intravesical BCG (Tice strain) therapy at that time. An acid-fast bacterial strain was isolated from his urine sample. We did not detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein 64 (MPT-64) antigen in the isolates obtained from his sample, and multiplex PCR and PCR-reverse blot hybridization assay indicated that the isolate was a member of the M. tuberculosis complex, but was not M. tuberculosis. Finally, sequence analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA and DNA gyrase, subunit B (gyrB) suggested that the organism was M. bovis or M. bovis BCG. Although we could not confirm that M. bovis BCG was the causative agent, the results of the 3 molecular methods and the MPT-64 antigen assay suggest this finding. This is an important finding, especially because M. bovis BCG cannot be identified using common commercial molecular genetics tools.

Bacillus Calmette-Guërin (BCG) has been traditionally used as a vaccine against tuberculosis. Further, intravesical administration of BCG has been shown to be effective in treating bladder cancer [1]. BCG contains a live attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis BCG); however, complications after bladder instillation of BCG are extreme-ly rare [2]. The few complications reported to date include high temperature followed by hematuria or granulomatous prostatitis, epididymo-orchitis, urethral obstruction, and systemic disease followed by dissemination of bacteria into other organs [3-5]. Here, we report a case of a M. bovis BCG infection that occurred after intravesical BCG therapy for bladder cancer.

A 67-yr-old male patient presented at our institution with azotemia. Three months before consulting our institute, he had visited a local clinic because he had been experiencing general weakness and poor oral intake. Biochemical and ultrasonographic examinations performed at the clinic, revealed elevated serum creatinine and obstruction of the left ureter, respectively. Other than a weight loss of 10 kg, the patient did not show any clinical features associated with M. bovis BCG infection, such as fever, chills, and night sweats. Right antegrade pyelography showed mild hydroureteronephrosis with focal stenosis in the ureteropelvic junction. The patient's history included diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure for which he had received intermittent hemodialysis. He had been diagnosed with bladder cancer 4 yr back, and he had undergone transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TUR-B), which was immediately followed by intravesical BCG therapy (Tice strain BCG; 12.5 mg of intravesical BCG was injected through a catheter into the bladder once every week for 6 weeks). A year later, another TUR-B was performed because atypical cells were observed in his urine, and a histological examination of his bladder indicated chronic granulomatous inflammation. Although, a diagnostic work-up for mycobacterial infections was not performed at that time, mycobacterial infection was suggested and the patient was administered isoniazid (300 mg/day), rifampicin (600 mg/day), ethambutol (800 mg/day), pyrazinamide (1 g/day), and pyridoxine (50 mg/day) for 3 months.

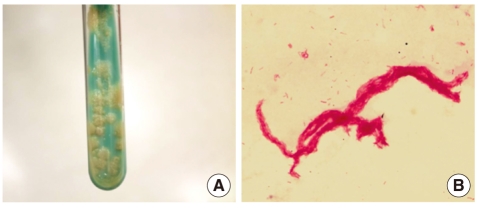

Laboratory testing performed upon admission at our institute yielded the following findings: proteinuria and pyuria in urinalysis, no microorganisms in Gram's staining of the urine sample, and acid-fast bacteria (AFB) in AFB staining of the voided urine. Mycobacteria were isolated by inoculating the patient's urine in Ogawa medium (solid egg-based medium) and by using the BACTEC MGIT 960 mycobacterial detection system (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The colony morphology and staining results of the isolated microorganism are shown in Fig. 1.

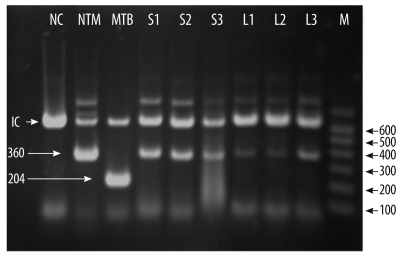

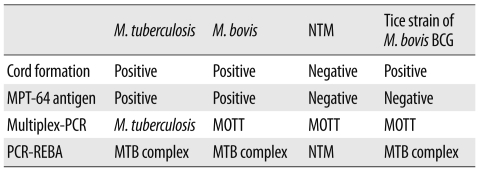

To identify the mycobacterial species present in the patient's samples, the Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein 64 (MPT-64) antigen assay, multiplex-PCR, and PCR-reverse blot hybridization assay (REBA) were performed. The MPT-64 antigen detection assay was performed using samples obtained from liquid cultures by using the TB Ag MPT64 Rapid kit (SD, Yongin, Korea). Multiplex-PCR and PCR-REBA were performed using the MTB-ID® V3 assay system (M&D, Wonju, Korea) and the REBA Myco-ID® assay system (M&D), respectively. The MPT-64 antigen is typically detected in specimens containing members of the M. tuberculosis (MTB) complex, which includes M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, Mycobacterium microti, Mycobacterium africanum, and other mycobacterial species. However, we did not detect this antigen in specimens from this patient. Multiplex-PCR allows differentiation of M. tuberculosis and mycobacterium other than tuberculosis (MOTT) on the basis of the band sizes (204 bp and 360 bp, respectively). In this study, we observed a band of 360 bp (Fig. 2). PCR-REBA allows differentiation of the MTB complex and non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) on the basis of the band position on a gel strip (refer to http://www.mndkorea.co.kr for details). In this case, the band pattern obtained after PCR-REBA suggested that the isolate belongs to the MTB complex. Thus, on the basis of the results obtained after performing multiplex-PCR and PCR-REBA, the microorganism isolated from the patient's samples was suspected to be a member of the MTB complex, but not M. tuberculosis. However, the 2 PCR methods and the assay for MPT-64 antigen yielded different results.

Hence, in order to identify the causative agent we performed sequence analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) and DNA gyrase, subunit B (gyrB). For sequence analysis, DNA was isolated using the MagNa Pure LC Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) as per the manufacturer's instructions. PCR for 16S rRNA and gyrB gene was performed in an ABI 9700 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the appropriate primer sets suggested by the CLSI [6] and Nakajima et al. [7]. Bi-directional sequence analysis was performed using the ABI Pri-sm BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI Prism 3730 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequence analysis showed that the 16S rRNA (696 bp) of the isolate had 100% similarity with that of M. bovis BCG (GenBank accession no. GU142938), M. tuberculosis (GenBank accession no. GU142936), M. caprae (GenBank accession no. NR028879), M. africanum (GenBank accession no. NR-025238), M. microti (GenBank accession no. NR025234), and M. bovis (GenBank accession no. BX248338). The analysis of the gyrB gene (479 bp) revealed a 100% similarity between the sequence of the isolate and the sequence of M. bovis BCG (GenBank accession no. AM408590, AP010918) and M. bovis (GenBank accession no. BX248334).

Complications caused by M. bovis BCG administration have been rarely reported. A retrospective study by Lamm et al. [2] suggests that local adverse effects, including cystitis, fever, hematuria, and prostatitis, are the most frequent complications, whereas extravesical complications are rare. Other local adverse effects include bladder contractures, epididymo-orchitis, ureteral obstruction, and renal abscesses with or without fistula formation. Although this patient did not show any significant symptoms, the laboratory findings indicated renal dysfunction and the results of right antegrade pyelography indicated mild ureteral stenosis. Mycobacterial infections occurring after intravesical administration of BCG have been rarely reported from Korea. Most of the cases reported to date were based on the pathological findings, and to our knowledge, there are no reports of cases in which the causative species of mycobacterium has been identified. To diagnose a mycobacterial infection, Nam et al. [8] and Jeon et al. [9] examined infected tissue showing chronic granulomatous inflammation with caseous necrosis. Lee et al. [10] and Kim et al. [11] used AFB staining to determine whether an infection was mycobacterial in nature. Son et al. [12] used PCR to determine whether an infection was caused by a mycobacterium but they were unsuccessful. Recently, Kim et al. [13] reported that a molecular method using multiplex PCR for the region of difference 1 (RD1), RD8, and RD14 can be used to confirm BCG infection. We hypothesized that M. bovis BCG was the causative agent in this case and attempted to identify this organism by mycobacterial cultivation, MPT-64 antigen assay, and other molecular methods.

MPT-64 is a 26-kDa secretory protein produced by M. tuberculosis, and the initially purified protein was a homolog from M. bovis BCG, MPB-64 [14, 15]. The MPT-64 antigen assay can specifically detect the MPT-64 antigen secreted by the tuberculosis-causing bacteria. Usually, detection of MPT-64 antigen in this assay is suggestive of the presence of an organism of the MTB complex, which includes M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. microti, and M. africanum. However, some strains of M. bovis BCG, such as Copenhagen, Glaxo, Pasteur, and Tice, do not express the MPB-64 gene [16, 17]. The absence of the MPT-64 antigen in our patient can be explained by the fact that the Tice BCG strain was injected into the patient's bladder. The multiplex-PCR and PCR-REBA methods used were not helpful in confirming whether the causative agent was M. bovis because these methods could not distinguish M. bovis from other members of the MTB complexes (Table 1). The sequence analysis of 16S rRNA and gyrB gene was useful in distinguishing the members of the MTB complex, but this method had a limited ability in clearly distinguishing between the M. bovis and M. bovis BCG strains.

Although we could not confirm that M. bovis BCG was the causative agent in this case, the methods employed, which included detection of MPT-64 antigen, PCR, and sequence analysis of 16S rRNA and gyrB gene, suggest that the causative agent is the Tice strain of M. bovis BCG. This is an important finding since M. bovis BCG cannot be identified using common commercial molecular genetics tools. The patient was treated with anti-mycobacterial agents for 3 months. Subsequently, AFB staining and mycobacterial culture were performed to detect any residual mycobacterial infection, but no mycobacteria were seen in both assessments.

References

1. Bellmunt J, Orsola A, Maldonado X, Kataja V. Bladder cancer: ESMO practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010; 21(S5):S134–S136.

2. Lamm DL, van der Meijden PM, Morales A, Brosman SA, Catalona WJ, Herr HW, et al. Incidence and treatment of complications of bacillus Calmette-Guérin intravesical therapy in superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 1992; 147:596–600. PMID: 1538436.

3. Harving SS, Asmussen L, Roosen JU, Hermann G. Granulomatous epididymo-orchitis, a rare complication of intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy for urothelial cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009; 43:331–333. PMID: 19396724.

4. Ilgan S, Koca G, Gundogdu S. Incidental detection of granulomatous prostatitis by F-18 FDG PET/CT in a patient with bladder cancer: a rare complication of BCG instillation therapy. Clin Nucl Med. 2009; 34:613–614. PMID: 19692827.

5. Korac M, Milosevic B, Lavadinovic L, Janjic A, Brmbolic B. Disseminated BCG infection in patients with urinary bladder carcinoma. Med Pregl. 2009; 62:592–595. PMID: 20491388.

6. CLSI. CLSI document MM18-A. Interpretive criteria for identification of bacteria and fungi by DNA target sequencing; approved guideline. 2008. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

7. Nakajima C, Rahim Z, Fukushima Y, Sugawara I, van der Zanden AG, Tamaru A, et al. Identification of mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates in Bangladesh by a species distinguishable multiplex PCR. BMC Infect Dis. 2010; 10:118. PMID: 20470432.

8. Nam SB, Park JS, Kim JJ, Park JT, Nam SK. Ureteral obstruction caused by periureteral tuberculous granuloma after intravesical BCG therapy for superficial bladder tumors. Korean J Urol. 2006; 47:436–439.

9. Jeon HJ, Ham WS, Lee SH, Kim WY, Kim JH, Cho SY, et al. Renal tuberculous granuloma after intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin instillation for bladder tumor. Korean J Urol. 2002; 43:1104–1106.

10. Lee GS, Lee GY, Yoon JC, Na DJ, Jeong SS, Sul CK, et al. Two cases of pulmonary complications following intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy in patients with superficial bladder cancer. Tuberc Respir Dis. 1999; 46:869–878.

11. Kim SH, Kim HW, Lee HJ, Bae WJ, Cho SY. Tuberculous prostatic abscess following intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin instillation. Korean J Urol. 2009; 50:186–187.

12. Son JI, Chung JP, Paek SS, Lee JI, Kim JH, Moon BS, et al. A case of granulomatous hepatitis developed after intravesical BCG instillation for bladder cancer. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2002; 39:375–378.

13. Kim SH, Kim SY, Eun BW, Yoo WJ, Park KU, Choi EH, et al. BCG osteomyelitis caused by the BCG Tokyo strain and confirmed by molecular method. Vaccine. 2008; 26:4379–4381. PMID: 18603342.

14. Nagai S, Wiker HG, Harboe M, Kinomoto M. Isolation and partial characterization of major protein antigens in the culture fluid of mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1991; 59:372–382. PMID: 1898899.

15. Harboe M, Nagai S, Patarroyo ME, Torres ML, Ramirez C, Cruz N. Properties of proteins MPB64, MPB70, and MPB80 of mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun. 1986; 52:293–302. PMID: 3514457.

16. Li H, Ulstrup JC, Jonassen TO, Melby K, Nagai S, Harboe M. Evidence for absence of the MPB64 gene in some substrains of mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun. 1993; 61:1730–1734. PMID: 8478061.

17. Behr MA, Small PM. A historical and molecular phylogeny of BCG strains. Vaccine. 1999; 17:915–922. PMID: 10067698.

Fig. 1

Colony morphology on solid medium (A) and cord formation by acid-fast bacillus (B) (Ziehl-Neelsen stain, ×1,000). The presence of cords is known to be a criterion for presumptive identification of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex.

Fig. 2

Multiplex-PCR to identify the isolate. Products of the multiplex-PCR performed using DNA from the isolates were separated on a 2.0% agarose gel using electrophoresis, and the gel was stained with ethidium bromide. The bands for the isolates (S1-S3 and L1-L3) corresponded to that for NTM. IC, internal control (660 bp); NC, negative control; NTM, control non-tuberculous mycobacteria; MTB, control Mycobacterium tuberculosis; S1-S3, isolates from solid media; L1-L3, isolates from liquid media; M, molecular markers.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download