Abstract

The chromosome band 11q23 is a common target region of chromosomal translocation in different types of leukemia, including infantile leukemia and therapy-related leukemia. The target gene at 11q23, MLL, is disrupted by the translocation and becomes fused to various translocation partners. We report a case of AML with a rare 3-way translocation involving chromosomes 1, 9, and 11: t(1;9;11)(p34.2;p22;q23). A 3-yr-old Korean girl presented with a 5-day history of fever. A diagnosis of AML was made on the basis of the morphological evaluation and immunophenotyping of bone marrow specimens. Flow cytometric immunophenotyping showed blasts positive for myeloid lineage markers and aberrant CD19 expression. Karyotypic analysis showed 46,XX,t(1;9;11)(p34.2;p22;q23) in 19 of the 20 cells analyzed. This abnormality was involved in MLL/MLLT3 rearrangement, which was confirmed by qualitative multiplex reverse transcription-PCR and interphase FISH. She achieved morphological and cytogenetic remission after 1 month of chemotherapy and remained event-free for 6 months. Four cases of t(1;9;11)(v;p22;q23) have been reported previously in a series that included cases with other 11q23 abnormalities, making it difficult to determine the distinctive clinical features associated with this abnormality. To our knowledge, this is the first description of t(1;9;11) with clinical and laboratory data, including the data for the involved genes, MLL/MLLT3.

Chromosomal 11q23 aberrations are frequently observed in infantile as well as therapy-related leukemias [1, 2]. The target gene at 11q23, MLL, is disrupted by the translocation and becomes fused to various translocation partner genes, which encode leukemia-specific chimeric proteins. Among cases involving 11q23 as an acquired abnormality in hematopoietic malignancies, the translocation between 9p22 and 11q23, t(9;11), is the second-most common translocation, and it usually occurs in French-American-British (FAB) types with a substantial monocytic element (M4 and M5, but particularly M5a) [1, 3]. The associated gene on 9p22 is known as MLLT3 and is predicted to encode a 63-kDa protein, which is a transcription activator [2]. The prognosis of patients with MLL/MLLT3 may not be as poor as in other MLL leukemias in de novo cases, but it is very poor in cases of secondary AML.

In particular, a complex 3-way translocation, t(9;11;v), involving a variable third chromosome has been described in many cases. However, the involvement of chromosome 1 is rare. Four cases with t(1;9;11)(v;p22;q23) have been reported in a series that included cases with other abnormalities of 11q23, making it difficult to determine the distinctive clinical features associated with this abnormality [3-5]. Here, we report a case of AML with t(1;9;11).

A 3-yr-old girl presented with a 5-day history of fever. On physical examination, it was found that she had anemic conjunctiva without organomegaly. Initial laboratory evaluation of peripheral blood revealed leukocytosis, anemia and thrombocytopenia: a white blood cell (WBC) count of 76.54×109/L with 86% abnormal myeloid cells, hemoglobin level of 5.6 g/dL, and a platelet count of 22×109/L.

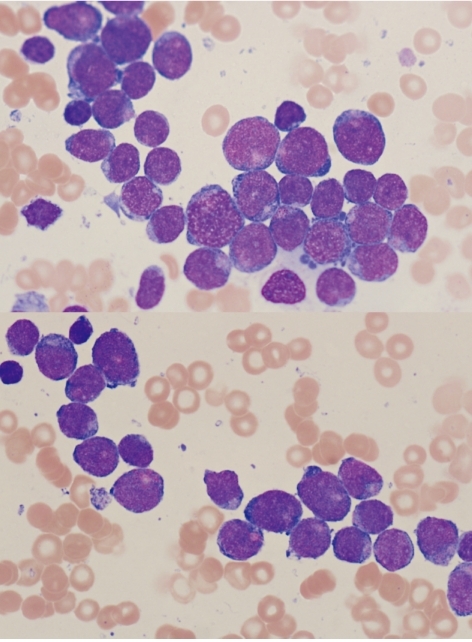

Bone marrow and peripheral blood smears were stained with Wright-Giemsa stain. The bone marrow specimens were immunophenotyped using a Cytomics FC 500 with CXP software (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Bone marrow biopsy revealed markedly hypercellular marrow with infiltration of leukemic blasts. In the bone marrow aspirate, 85.6% of nucleated cells were blasts, which were small- to medium-sized cells with coarse nuclear chromatin, distinct nucleoli, and basophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 1). In flow cytometric immunophenotyping, the population of blasts was positive for CD13, CD19, CD33, CD34, CD117, and MPO but negative for CD2, CD3, CD5, CD7, CD10, CD14, CD20, CD22, and CD56. Therefore, a diagnosis of AML with aberrant CD19 expression was made. The patient did not show central nervous system (CNS) involvement.

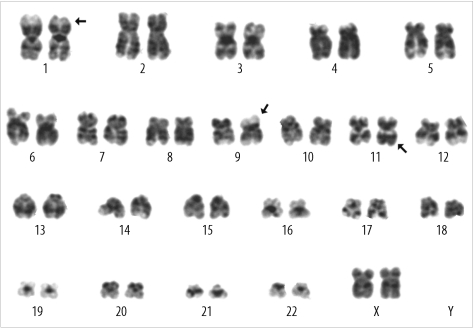

Cytogenetic and FISH analyses were performed on unstimulated 24-hr and 48-hr cultures of bone marrow cells according to standard techniques. The G-banded metaphases were prepared with trypsin/Wright stain. For qualitative multiplex reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), RNA was extracted from bone marrow specimens with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The multiplex gene rearrangement test was performed using a Hemavision™ kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) to detect 28 types of fusion transcripts. Karyotypic analysis showed a karyotype of 46, XX,t(1;9;11)(p34.2;p22;q23) in 19 of the 20 cells analyzed: 46,XX,t(1;9;11)(p34.2;p22;q23)[19]/46,XX[1] (Fig. 2). Using qualitative multiplex RT-PCR, we found that this abnormal karyotypic clone had an MLL/MLLT3 rearrangement. This rearrangement was confirmed by interphase FISH using the LSI MLL Dual-Color, Break Apart Rearrangement Probe (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA). Cells with MLL rearrangement comprised 92% of the 200 cells observed at diagnosis.

The patient received induction chemotherapy with cytarabine, daunorubicin, and etoposide, which was followed by consolidation chemotherapy. At the end of the first induction chemotherapy, bone marrow examination and cytogenetic analysis demonstrated no evidence of leukemic blasts or abnormal karyotypic clones, but FISH analysis showed that 11% of the leukemic clones had persisted. A follow-up FISH study at 2 months after diagnosis showed that MLL rearrangement was not present. After the first remission, she remained event-free for 6 months.

The study of a large series of patients with 11q23 rearrangement showed that patients with 11q23 rearrangement should not be homogeneous [3-6]. The partner chromosome, age, diagnosis, WBC, CNS involvement, and the presence of other karyotypic abnormalities had significant effects on the clinical presentation and treatment outcome [3, 6]. In particular, t(9;11)(p22;q23) has a better prognosis than translocations between 11q23 and other chromosomes. Cases of complex three-way translocations including chromosome 1, such as t(1;9;11), are rare and their prognostic significance is unclear.

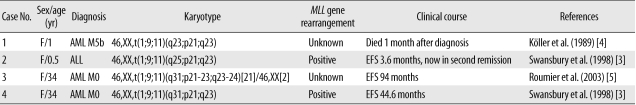

There are 4 case reports regarding t(1;9;11)(v;p21-22;q23) in the literature; these reports describe the findings for an infant with AML M5b, an infant with ALL, and 2 female adults with AML M0 (Table 1) [3-5]. They have been included in a series of cases showing 11q23 abnormality with different partner chromosomes, making it difficult to determine the distinctive clinical features associated with t(1;9;11). In these previous studies, the patients did not have any additional chromosomal abnormalities except t(1;9;11). Despite their shared cytogenetic abnormalities, there were differences in morphological diagnosis and clinical progress. These clinical differences may appear to reflect the age at diagnosis, i.e., one infant died 1 month after diagnosis and the other had an event-free survival of 3.6 months in second remission, but the 2 adults had relatively long event-free survivals (44.6 and 94 months). In our patient, a 3-yr-old girl with a diagnosis of AML M1, cytogenetic study also indicated t(1;9;11) as the sole abnormality. She achieved morphological and cytogenetic remission after 1 month of chemotherapy and was event-free for 6 months. Taken together, these observations suggested that patients with t(1;9;11) in de novo leukemia have different clinical courses depending on age. The prognosis of patients with the t(1;9;11) MLL/MLLT3 variant may not be as poor as that of other child or adult MLL leukemia cases, but it is very poor in cases of infants. However, it is possible that there are other causes such as unknown involved gene(s) on chromosome 1, CNS involvement, and treatment protocol, but we cannot find any description in their literatures [3-5]. Further studies are needed.

Here, we report a case of AML with t(1;9;11). To our knowledge, this is the first description of t(1;9;11) with clinical and laboratory characteristics, including detection of the involved genes, MLL/MLLT3.

References

1. Sandoval C, Head DR, Mirro J Jr, Behm FG, Ayers GD, Raimondi SC. Translocation t(9;11)(p21;q23) in pediatric de novo and secondary acute myeloblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1992; 6:513–519. PMID: 1602790.

2. Joh T, Kagami Y, Yamamoto K, Segawa T, Takizawa J, Takahashi T, et al. Identification of MLL and chimeric MLL gene products involved in 11q23 translocation and possible mechanisms of leukemogenesis by MLL truncation. Oncogene. 1996; 13:1945–1953. PMID: 8934541.

3. Swansbury GJ, Slater R, Bain BJ, Moorman AV, Secker-Walker LM. Hematological malignancies with t(9;11)(p21-22;q23)--a laboratory and clinical study of 125 cases. European 11q23 Workshop participants. Leukemia. 1998; 12:792–800. PMID: 9593283.

4. Köller U, Haas OA, Ludwig WD, Bartram CR, Harbott J, Panzer-Grümayer R, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity in infant acute leukemia. II. Acute nonlymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 1989; 3:708–714. PMID: 2779287.

5. Roumier C, Eclache V, Imbert M, Davi F, MacIntyre E, Garand R, et al. M0 AML, clinical and biologic features of the disease, including AML1 gene mutations: a report of 59 cases by the Groupe Français d'Hématologie Cellulaire (GFHC) and the Groupe Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique (GFCH). Blood. 2003; 101:1277–1283. PMID: 12393381.

6. Mrózek K, Heinonen K, Lawrence D, Carroll AJ, Koduru PR, Rao KW, et al. Adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia and t(9;11)(p22;q23) have a superior outcome to patients with other translocations involving band 11q23: a cancer and leukemia group B study. Blood. 1997; 90:4532–4538. PMID: 9373264.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download