Abstract

A 42-yr-old man with hepatitis B virus associated liver cirrhosis was admitted to the emergency room because of multiple seizures, a history of chills and myalgia over the previous 2 weeks, and 3 days of melena. He was febrile with a temperature of 38.0℃. There were no symptoms and signs related to the genitourinary system, skin, or joints. Three sets of blood cultures were obtained and oxidase-positive, gram-negative diplococci were detected after 25.9-26.9 hr of incubation in all aerobic vials. The organism was positive for catalase and oxidase, and was identified as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, using a Vitek Neisseria-Haemophilus Identification card (bioMérieux Vitek, Inc., USA). Further, 16S rRNA sequencing of this isolate revealed a 99.9% homology with the published sequence of N. gonorrhoeae strain NCTC 83785 (GenBank Accession No. NR_026079.1). Acute bleeding by variceal rupture seems to be a likely route of introduction of N. gonorrhoeae from the mucosa into the blood. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of gonococcal bacteremia in Korea.

Go to :

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a well-known cause of sexually transmitted diseases such as genital, pharyngeal, and anorectal infections [1]. Bloodstream invasion, however, occurs only in 0.5-3% of the infections and results in disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) [1]. Only one case of DGI has been reported previously in Korea [2]. Here, we report a patient with N. gonorrhoeae bacteremia in whom massive variceal hemorrhage occurs coincidently.

Go to :

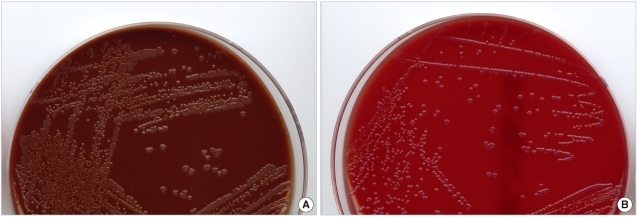

On June 5th, 2010, a 42-yr-old man was admitted to the hospital via the emergency room due to multiple seizures, a history of chills, myalgia over the previous 2 weeks, and 3 days of melena. Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-associated liver cirrhosis was diagnosed 2 yr ago. The patient was treated in a primary clinic and his cough improved; however, myalgia and melena continued and worsened after 4 days. At admission, he was pale and febrile with a temperature of 38.0℃. Intermittent fever of 37.8-38.0℃ continued until hospital day 3. The patient had a blood pressure of 108/64 mmHg, a pulse of 86/min, and a respiratory rate of 20/min. There were no signs and symptoms related to the genitourinary systems, skin, and joints. L-tube irrigation was performed, and the aspirate was bloody and had old clots. Laboratory investigations showed a Hb of 4.6 g/dL, a leukocyte count of 19.4×103/mm3, a platelet count of 51×103/mm3, a C-reactive protein level of 10.56 mg/dL, prothrombin time (international normalized ratio) of 1.58, AST/ALT of 56/55 IU/L, ALP of 102 IU/L, BUN/creatinine of 37/1.1 mg/dL, and total protein/albumin of 3.5/1.5 g/dL. Three sets of blood cultures were taken and gram-variable cocci in clusters were detected after a 25.9- to 26.9-hr incubation in aerobic vials. Initially, cocci were reported as gram-positive. In 5% CO2 at 35℃, tiny, glistening, and raised colonies grew after overnight incubation. The colonies grew to 1-2 mm in diameter after a 2-day incubation on both blood agar and chocolate agar plates (Fig. 1). No growth was observed on MacConkey agar. The bacterium was positive for catalase, oxidase, and acid production from glucose but not maltose. It was identified, with 98% probability, as N. gonorrhoeae (bionumber 464001) by the Vitek Neisseria-Haemo-philus Identification (NHI) card (bioMérieux Vitek, Inc., Hazelwood, MO, USA). Gram staining of the colonies revealed gram-negative diplococci. Sequencing of 16S rRNA covering nucleotides 30-1,370 of this isolate showed the greatest homology (99.9%) to the published sequence of N. gonorrhoeae strain NCTC 83785 (GenBank Accession No. NR_026079.1), followed by 98.6% homology to Neisseria meningitidis 8013 (GenBank Accession No. FM 999788.1). The isolate was penicillinase-positive on an NHI card. It was resistant to penicillin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline; and susceptible to cefuroxime, cefotaxime, and cefepime by disk diffusion on GC agar plates after a 20- to 24-hr incubation at 35℃ and 5% CO2 [1]. The patient received endoscopic variceal ligation to control hemorrhage of esophageal varices. Cefotaxime was started empirically in the emergency room, and vancomycin was added after the report of positive blood cultures of gram-positive cocci on day 2. On day 3, fever was no longer present, and follow-up blood cultures were negative. The patient was discharged on day 8. He received variceal ligation twice more: 1 and 2 months later. Urine and throat swabs were obtained when he visited the outpatient clinic on September 28th, and were cultured on modified Thayer-Martin agar plates and blood agar plates. All were negative for N. gonorrhoeae. At that time, he reported that he had not had sexual contact with his wife for several months, and that he had traveled to China during the previous April. He has a son.

Go to :

N. gonorrhoeae is a pathogenic Neisseria species that mainly causes genital infections, and, less frequently, also causes pharyngeal and anorectal infections [2, 3]. Dissemination occurs in only 0.5-3% of the gonococcal infections [2, 3]. Disseminated infections typically present with low-grade fever, skin lesions, tenosinovitis, and migratory polyarthralgias [2, 3]. Only one case of DGI with polyarthralgias and skin lesions has been previously reported in Korea [4]. This is the second case of DGI, and, to the best of our knowledge, the first culture-proven bacteremia of N. gonorrhoeae in Korea [4]. DGI is often preceded by asymptomatic mucosal infections. Predisposing risk factors for dissemination include being a female, a homosexual or bisexual male, recent menstruation, pregnancy, immediate postpartum states, gonococcal pharyngitis, complement deficiencies, and systemic lupus erythematosus [2, 3, 5]. Because this patient had HBV-associated liver cirrhosis, he may have had a complement deficiency [6, 7]. Liver cirrhosis patients are susceptible to immune and nutritional deficiencies, including vitamin, protein, immunoglobulin, and complement deficiencies [6-8], which cause increased morbidity and mortality of infectious diseases [9, 10]. Although the patient's medical history and physical examinations related to other risk factors were not taken initially in this case, he had neither female-related risk factors nor exhibited homosexual behavior.

Because the patient had no symptoms related to the skin or joints, DGI was hardly suspected, even when N. gonorrhoeae was identified from blood cultures. In this case, intermittent fever, a leukocyte count of 19.4×103/mm3, and a C-reactive protein level of 10.56 mg/dL indicated a stage of acute inflammation. Therefore, there was on acute onset of dissemination of N. gonorrhoeae at admission without time enough to involve skin and the joints. Gonococcal bacteremia is often intermittent and only half of the patients with DGI have positive cultures from blood or synovial fluid [3]. Positive results, with practically the same time to positivity in all three sets of blood cultures, suggested direct introduction of N. gonorrhoeae into the blood stream, or endocarditis, a rare, life-threatening condition of DGI. However, no signs or symptoms of endocarditis were observed during a 6-month follow-up. Esophageal variceal rupture was the only mucosal breakage in this case. Therefore, it was speculated that asymptomatic gonococcal pharyngitis preceded dissemination, and that ruptured vessels on the esophageal mucosa were a likely route of N. gonorrhoeae dissemination.

The N. gonorrhoeae isolated from this patient was penicillinase-positive, resistant to penicillin, ciproflocxacin, and tetracycline, but sensitive to cefuroxime, cefotaxime, and cefepime. This resistance pattern was consistent with the previous report of resistance rates of Korean gonococcal isolates against penicillin, quinolone, tetracycline, and ceftriaxone (55.4%, 95.7%, 10-34%, and 0%, respectively, in 2008) [11]. For treatment of DGI, intramuscular or intrave-nous injection of 1 g ceftriaxone every 24 hr is recommend-ed and it should be continued for 24-48 hr after an improvement of symptoms is observed [12]. Initial 7-day empirical therapy of cefotaxime should be sufficient to provide a bacteriological cure, and prevent progression of DGI in this case [12].

Biochemical testing of this organism indicated N. gonorrhoeae; however, fair growth of the bacteria on blood agar as well as on chocolate agar made that identification more suspicious because it is known that some N. gonorrhoeae strains can grow, but more slowly, and less well, on commercially available sheep blood agar [13]. The pathogens were detected from all vials between 25.9 and 26.9 hr. This is longer than the average detection time for common gram-negative pathogens isolated from blood cultures [14]. Severe liver cirrhosis complicated with variceal hemorrhage is clearly associated with an increased risk of bacteremia by opportunistic pathogens that live in the gastrointestinal tract, such as Enterobacteriaceae and Staphylococcus aureus [15-17]. Bacterial infections have been reported among 35-66% of patients with cirrhosis who have variceal hemorrhage [17, 18]. Thus, 16S rRNA sequencing was required to confirm the identification. Certain strains such as Por1A serovar and AHU auxotype are alleged to be prone to dissemination; however, this assumption has been challenged [3] and these strains are rare in Korea [19]. Further phenotypic or serologic characterization of this isolate was not performed.

In this case, unusual clinical conditions of the patient, combined with the microbiological characteristics of the isolates, postponed the identification of N. gonorrhoeae. Hemorrhage of esophageal varices should be considered as a risk factor for DGI in patients in which N. gonorrhoeae grows from blood cultures.

Go to :

References

1. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. Twentieth informational supplement, M100-S20. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 2010. Wayne, PA: Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute;p. 84–86.

2. Winn WC, Allen SD, editors. Koneman's color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology. 2006. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;p. 574–578.

3. Marrazzo JM. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, editors. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 2005. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;p. 2762–2765.

4. Kim GC, Lee CH, Lee JS, Chung MH, Choi JH, Moon YS. A case of concomitant disseminated gonococcal infection with acute viral hepatitis C. Infect Chemother. 2004; 36:175–180.

5. Ellison RT 3rd, Curd JG, Kohler PF, Reller LB, Judson FN. Underlying complement deficiency in patients with disseminated gonococcal infection. Sex Transm Dis. 1987; 14:201–204. PMID: 2830678.

6. Kourilsky O, Leroy C, Peltier AP. Complement and liver cell function in 53 patients with liver disease. Am J Med. 1973; 55:783–790. PMID: 4796289.

7. Homann C, Varming K, Høgåsen K, Mollnes TE, Graudal N, Thomsen AC, et al. Acquired C3 deficiency in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis predisposes to infection and increased mortality. Gut. 1997; 40:544–549. PMID: 9176087.

8. Sobhonslidsuk A, Roongpisuthipong C, Nantiruj K, Kulapongse S, Songchitsomboon S, Sumalnop K, et al. Impact of liver cirrhosis on nutritional and immunological status. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001; 84:982–988. PMID: 11759979.

9. Ashare A, Stanford C, Hancock P, Stark D, Lilli K, Birrer E, et al. Chronic liver disease impairs bacterial clearance in a human mo-del of induced bacteremia. Clin Transl Sci. 2009; 2:199–205. PMID: 20443893.

10. Cho JH, Park KH, Kim SH, Bang JH, Park WB, Kim HB, et al. Bacteremia is a prognostic factor for poor outcome in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007; 39:697–702. PMID: 17654346.

11. Tapsall JW, Limnios EA, Abu Bakar HM, Darussalam B, Ping YY, Buadromo EM, et al. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the WHO Western Pacific and South East Asian regions, 2007-2008. Commun Dis Intell. 2010; 34:1–7. PMID: 20521493.

12. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006; 55:1–94. PMID: 16888612.

13. Janda W, Gaydos C. Murray PR, Baron EJ, editors. Neisseria. Manual of clinical microbiology. 2007. 9th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press;p. 608.

14. Park SH, Shim H, Yoon NS, Kim MN. Clinical relevance of time-to-positivity in BACTEC9240 blood culture system. Korean J Lab Med. 2010; 30:276–283. PMID: 20603588.

15. Bert F, Johnson JR, Ouattara B, Leflon-Guibout V, Johnston B, Marcon E, et al. Genetic diversity and virulence profiles of Escherichia coli isolates causing spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and bacteremia in patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010; 48:2709–2714. PMID: 20519468.

16. Kang CI, Song JH, Ko KS, Chung DR, Peck KR. Clinical significance of Staphylococcus aureus infection in patients with chronic liver diseases. Liver Int. 2010; 30:1333–1338. PMID: 20492505.

17. Rerknimitr R, Chanyaswad J, Kongkam P, Kullavanijaya P. Risk of bacteremia in bleeding and nonbleeding gastric varices after endoscopic injection of cyanoacrylate. Endoscopy. 2008; 40:644–649. PMID: 18561097.

18. Goulis J, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Bacterial infection in the pathogenesis of variceal bleeding. Lancet. 1999; 353:139–142. PMID: 10023916.

19. Yum JH, Shin SW, Ryeom G. Auxotype and antibiotic resistance pattern of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated in Korea. J Korean Soc Microbiol. 1995; 30:507–515.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download