INTRODUCTION

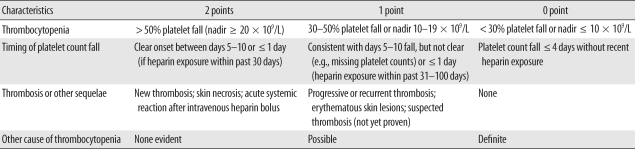

Table 1

Pretest probability score: 6-8 = high; 4-5 = moderate; 0-3 = low. Modified from Greinacher and Warkentin [1].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients and methods

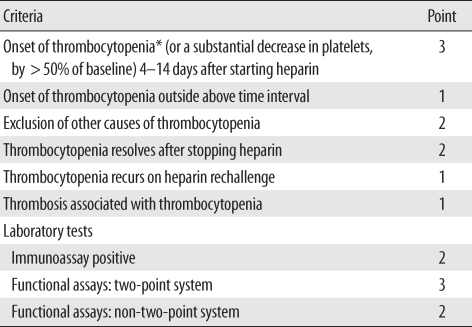

Table 2

Modified from Chong and Chong [2].

*The presence of thrombocytopenia is mandatory. Thrombocytopenia is defined as a platelet count below 150 × 109/L. If the total point is >7, 5-6, 3-4, and <3, the diagnosis of HIT is considered definite, probable, possible, and unlikely, respectively.

Abbreviation: HIT, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

2. Statistical analysis

RESULTS

1. Patient characteristics

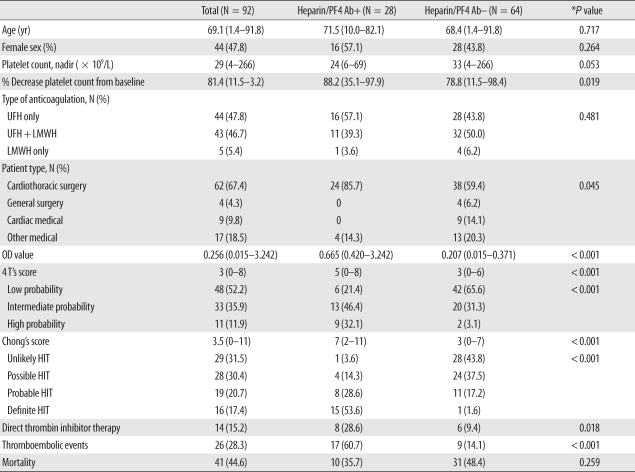

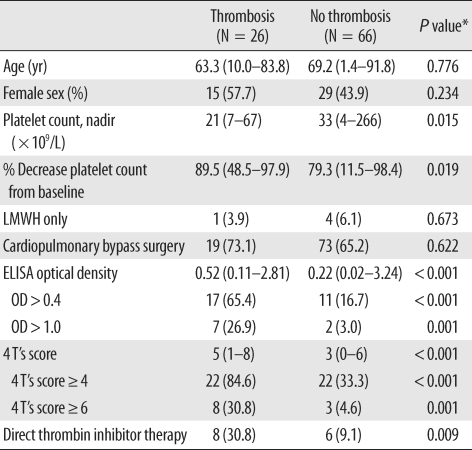

Table 3

*P value: chi-square test for categorical variables and Man-Whitney U test for continuous variables.

Data are shown as the median (range) for continuous variables or the number (percentage) for categorical variables unless otherwise indicated. Heparin/PF4 Ab was measured by a commercial ELISA kit, and positive results were defined as optical density (OD) value ≥ 0.4.

Abbreviations: PF4, platelet factor 4; Ab, antibody; UFH, unfractionated heparin; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; OD, optical density; HIT, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

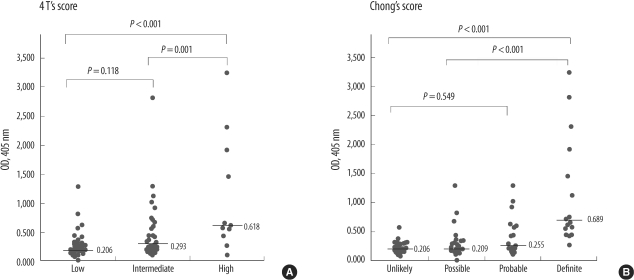

2. Diagnostic performance of HIT scoring systems and heparin/PF4 antibody ELISA OD values

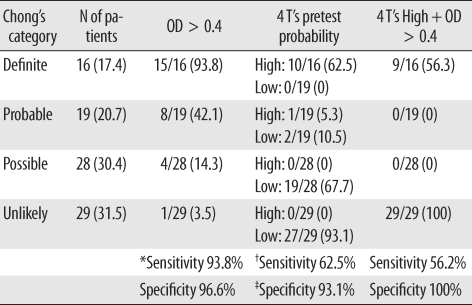

Table 4

*Sensitivity and specificity were defined for the 45 patients in the Definite and Unlikely HIT categories by Chong's scoring system; †Sensitivity of high pretest probability was defined for the patients in the Definite HIT category by Chong's scoring system; ‡Specificity of low pretest probability was defined for the patients in the Unlikely HIT category by Chong's scoring system.

Data are shown as the number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: PF4, platelet factor 4; OD, optical density.

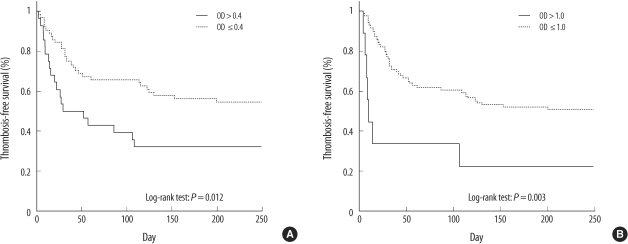

3. Thrombosis and mortality

| Fig. 2Frequency of thromboembolic complications according to heparin/PF4 ELISA optical density (OD) level increment. The numbers on each bar indicate the number of patients. |

| Fig. 3ROC curve relating heparin/PF4 ELISA (A) optical density (OD) value and (B) 4 T's scores to occurrence of thromboembolic complication. (A) When the OD cut-off is 0.427, the sensitivity is 65.4%, and the specificity is 88.4%. (B) When the 4 T's score is greater than or equal to 4, the sensitivity is 69.2%, and the specificity is 84.8%.

Abbreviation: AUC, area under curve.

|

Table 5

*P value: chi-square test for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables.

Data are shown as the median (range) for continuous variables or the number (percentage) for categorical variables unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; OD, optical density.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download