Abstract

Acinar cell carcinoma (ACC) of the pancreas is a rare malignancy making up approximately 1% of pancreatic non-endocrine malignant tumors. The common finding on computed tomography is a solitary, well-defined, heterogenous hypodense mass with enhancing capsule. ACC is a highly cellular tumor with minimal stroma and a lack of stromal desmoplasia. The accurate diagnosis of ACC cannot typically be done by histology alone but rather requires immunohistochemical staining or electron microscopy for the identification of pancreatic enzymes and zymogen granules. ACC has been considered a cancer with a poor prognosis due to frequent metastasis, a high recurrence rate, and low respectability. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice that can lead to long-term survival. ACC has a better prognosis than ductal carcinoma of the pancreas, but a worse prognosis compared to islet cell carcinoma. We report two cases of ACC with 5-year survival after surgical resection.

Acinar cell carcinoma (ACC) of the pancreas is a rare, malignant tumor with a poorly defined natural history.

The pancreas is composed predominantly of acinar cells (82%), followed by islet cells (14%) and ductal cells (4%). However, ACC accounts for less than 1% of all pancreatic malignancies, as compared to pancreatic adenocarcinoma which represents 75%.(1) ACC, first described in 1908 by Berner, recapitulates the growth pattern and secretory products of normal pancreatic acini, often producing digestive enzymes such as trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase, and amylase.(2)

According to the literature, this tumor of exocrine pancreas has only been studied in the literature through small retrospective case series. Given its low incidence, characterizing and analyzing the natural history of ACC and the appropriate therapeutic approach remains difficult and unclear with current guidelines based on a limited number of cases.(3) Recently, large group studies in Japan (n=115) and the USA (n=865) have been reported.(4,5) However, because of the low incidence and poor prognosis of ACC, there have been a few reports on the long-term survival more than 5 years after surgical resection.

We report on two female patients of ACC who were treated at a single center. We describe the clinical, diagnostic, and pathologic features of these tumors with long-term (more than 5 years) follow-up and a review the literature.

The patient's clinical and pathologic data are presented in Table 1.

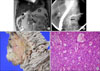

A 60-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus presented in May 2004 with abdominal pain. An initial computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showed fluid accumulation and fatty infiltration around the pancreas, so the initial diagnosis was made of acute pancreatitis. CT also revealed a hypervascular mass in the body of the pancreas. After the pancreatitis resolved, a follow-up CT showed a 2.5 cm well-enhanced mass lesion with exophytic features on the body. There was also a heterogenous 2 cm low-attenuated lesion around the head of the pancreas (Fig. 1A). Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated the possibility of pancreatic cancer on the head with bleeding and islet cell tumor on the body with pancreatic duct invasion. A pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed. On gross examination, the head of the pancreas showed a relatively well defined and grayish-white round mass that measured 1 cm in diameter (Fig. 1B). The capsule was not grossly invaded and the tumor invaded the pancreatic duct. On section, the pancreatic duct showed a dilated portion in the 2.3 cm from ampulla of Vater. We also found a 2.5 cm non-functioning islet cell tumor on the pancreatic body. All lymph nodes were negative. On microscopic findings, the tumor of pancreatic head showed moderate differentiated acinar cell carcinoma with trabecular type (Fig. 1C). Immunohistochemistry was positive for α1-antitrypsin, lipase, cytokeratin, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), distase-PAS and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). It was negative for chromogranin, cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 20, and α-fetoprotein. There was focal positivity for neurone specific enolase. The patient's convalescence was unremarkable. However, a postoperative 29 month, follow-up CT scan showed liver metastasis (segment II, 3 cm and VII, 1.3 cm). She treated a single of transarterial chemoembolization and began chemotherapy with gemcitabine and capecitabine. Currently, the metastatic lesions of the liver are growing in size despite chemotherapy (Fig. 1D), but her general condition is fair at present.

A 48-year-old woman was admitted in November 2003 with chest tightness. The patient had a past medical history of chronic hepatitis B and diabetes mellitus for 5 years. Upon physical examination, there was no tenderness in abdomen. In routine laboratory tests, serum amylase and lipase showed a mild increases: 120 U/L (normal<100) and 100 U/L (normal<60), respectively. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) was remarkably increased to 89.95 U/L. An abdominal ultrasonography (US) showed diffuse dilatation of the pancreatic duct in the body. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed focal stenosis of pancreatic duct in the head and diffuse duct dilatation (0.7 cm diameter) of the body and tail (Fig. 2A). ERCP findings showed a filling defect of pancreatic duct between the head and body, as well as diffuse dilatation of the body and tail of pancreatic duct (Fig. 2B). Imaging studies were compatible with pancreatic head cancer. A pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed, and there was no evidence of lymph node enlargement or peritoneal tumor spread. Palpation of the pancreas revealed a hard lesion on the uncinate process. The pancreatic parenchyma contained focal and irregular fibrotic lesions near the uncinate process, measuring 1.2×1cm in diameter (Fig. 2C). The pancreatic duct was grossly unremarkable. Microscopic findings demonstrated infiltrative solid tumor nests with tumor cells that had relatively uniform oval nuclei (Fig. 2D). Immunohistochemistry was positive for cytokeratin and negative for chromogranin and synaptophysin. The postoperative course was unremarkable and the patient was discharged 20 days after the operation. She is well with no evidence of disease 71 months after the surgery.

The clinical features and prognosis of ACC are summarized in Table 2.(1,3-9) Both of our patients were female, but previous reports including Klimstra et al.(1) and Holen et al.(7) suggested that ACC is more common in men. These findings were confirmed by large-scale studies in Japan(4) and the USA(5). It remains to be seen if gender is a major risk factor for ACC. Some studies involving more than 20 patients reported a median age of 57~67.(1,3,7) ACC of the pancreas had a more lower median age than ductal cell carcinoma. In particular, the median age of Japanese ACC was lower than that of Western.

The presenting symptoms of patients with ACC are usually non-specific. Symptoms commonly include abdominal pain, weight loss, and nausea/vomiting. Jaundice is less frequently associated with ACC compared to ductal adenocarcinoma. This difference could be due to ACC being more commonly found on the body and tail of the pancreas. This represents a possible distinguishing factor from ductal adenocarcinoma.(3) Levels of tumor markers such as CEA, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and SPAN-1 are not useful for making a differential diagnosis. However, high AFP in pancreatic tumors may suggest ACC if the CA19-9 level has normal range.(4) In our second case, a high level of AFP was present despite the small size of the tumor.

When a pancreatic malignancy is suspected based on symptoms or increased tumor markers, abdominal US, CT, EUS, and ERCP are useful in establishing both a preliminary diagnosis and treatment approach. However, a preoperative diagnosis is generally difficult because of somewhat nonspecific descriptions and a limited number of cases, although CT occasionally provides diagnostic clues. Chiou et al.(8) suggested that ACC generally presents with heterogenous, hypodense masses on CT and is notable for well-defined enhancing capsules with occasional internal calcification. Oh et al.(10) recommended that ACC should be differentiated from other pancreatic neoplasms if a large, well encapsulated, strongly enhanced pancreatic mass showing central necrosis is observed during the arterial phase of a spiral CT.

The accurate diagnosis of ACC requires a thorough histopathological examination of specimens obtained through biopsy or operation. Tissue diagnosis often requires additional immunohistochemical assays or electron microscopy for definite confirmation of ACC due to the cytological and histological similarity of ACC to endocrine tumors. Macroscopically, ACC is usually a large, well-circumscribed lesion, ranging in size from 2 to 30 cm. On gross examination, they often appear yellowish or tan in color with a soft and lobulated consistency.(6) ACC has distinctive microscopic features. Acinar structures are the hallmark of this tumor under a light microscope. ACC exhibits acini with peripherally placed nuclei and small apical lumens, trabeculae, glands, or diffuse sheets of cells separated by minimal fibrovascular stroma.(6) The cells usually display uniform nuclei with rare pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli. The most characteristic ultrastructural finding is the identification of zymogen granules. Immunohistochemical markers for ACC include trypsin, which is most common expressed, followed by lipase, chymotrypsin and amylase. The high incidence of trypsin reactivity in ACC makes it a distinguishable specific marker for lesions which otherwise appear similar.(2)

Completely surgical resection is the best first-line treatment for ACC, if it is possible. As shown in Table 2, Holen et al.(7) and Seth et al.(3) reported a median disease-free survival of 14 and 25 months and a median actuarial survival of 36 and 33 months for resected patients, respectively. A large-group database study in Japan and the USA suggested that the survival rate for ACC is better than for ductal cell carcinoma in any stage. Furthermore, survival can be improved by resection, even in advanced patients.(4,5) The operability of ACC is much higher than for ductal cell carcinoma (76% versus 20~30%).(4) The reason for the high rate of resection is because vascular invasion and lymph node metastasis are less likely to occur and invasion to the surrounding tissue is minimal. Tumor size, or T classification, and nodal involvement were not independent predictors of survival.(5) Therefore, aggressive surgical resection with negative margins prolongs better survival and offers the best chance of cure. No large studies exist which describe the neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment of ACC with radiation or chemotherapy. However, if ACC is unresectable or recurs after resection, chemotherapy may be a valid option.

The prognosis for ACC is generally poor. Patients often present with metastases and have a high incidence of recurrence.(7) However, resected patients have a better prognosis, compared to those with more common pancreatic adenocarcinomas. The vascular invasion related to ACC is not common and the incidence of metastases to lymph nodes or distant organs is lower compared to that of ductal cell carcinoma.(4) Holen et al.(7) and Seth et al.(3) reported high recurrence rates of 72% and 57%, respectively, representing both local and distant metastases. The high recurrence rate of ACC suggests that this malignancy is aggressive and creates distant micrometastases which are often not found despite well-circumscribed local disease.(7)

The two patients described in our cases were admitted with pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus-associated symptoms, respectively. The masses on the pancreas were detected incidentally by abdominal imaging which was performed upon admission. We concluded that the early detection of small ACC lesions led to a relatively good prognosis. Surgical resection for ACC should be actively performed in order to improve the chances for long-term survival. Further characterization of these tumors in terms of their etiology, clinical and histopathological manifestations, therapeutic approach, and prognosis will help distinguish them from more common malignancies of the pancreas, such as adenocarcinoma and endocrine tumors.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A) Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan reveals heterogenous 2 cm low-attenuated lesion (arrow) around head of pancreas (portal phase). (B) Cut surface of tumor shows relatively well-defined and grayish-white round mass. (C) Tumor demonstrates trabecular growth pattern of acinic tumor cells (H&E stain, ×200). (D) Contrast-enhanced coronal CT scans show two metastatic tumors within segment II of liver on 58 months after surgery (portal phase). |

| Fig. 2(A) Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography shows focal stenosis (arrow) of pancreatic duct in head and diffuse duct dilatation of body and tail. (B) Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography findings shows filling defect (arrow) of pancreatic duct between head and body, as well as diffuse dilatation of body and tail of pancreatic duct. (C) Pancreatic head reveals an ill-defined whitish multi-nodular solid mass, measuring 1.2 cm in diameter. (D) Microscopic view demonstrates mostly solid and focally tubular tumor nests. Tumor cells have relatively uniform oval nuclei and moderate amount eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (H&E stain, ×400). |

References

1. Klimstra DS, Heffess CS, Oertel JE, Rosai J. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992. 16:815–837.

2. Caruso RA, Inferrera A, Tuccari G, Barresi G. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. A histologic, immunocytochemical and ultrastructural study. Histol Histopathol. 1994. 9:53–58.

3. Seth AK, Argani P, Campbell KA, Cameron JL, Pawlik TM, Schulick RD, et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: an institutional series of resected patients and review of the current literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008. 12:1061–1067.

4. Kitagami H, Kondo S, Hirano S, Kawakami H, Egawa S, Tanaka M. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: clinical analysis of 115 patients from Pancreatic Cancer Registry of Japan Pancreas Society. Pancreas. 2007. 35:42–46.

5. Schmidt CM, Matos JM, Bentrem DJ, Talamonti MS, Lillemoe KD, Bilimoria KY. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas in the United States: prognostic factors and comparison to ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008. 12:2078–2086.

6. Ordóñez NG. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001. 8:144–159.

7. Holen KD, Klimstra DS, Hummer A, Gonen M, Conlon K, Brennan M, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes from an institutional series of acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas and related tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002. 20:4673–4678.

8. Chiou YY, Chiang JH, Hwang JI, Yen CH, Tsay SH, Chang CY. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: clinical and computed tomography manifestations. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004. 28:180–186.

9. Webb JN. Acinar cell neoplasms of the exocrine pancreas. J Clin Pathol. 1977. 30:103–112.

10. Oh JY, Nam KJ, Choi JC, Suh SB, Lee KN, Park BH, et al. CT findings of acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: focused on spiral CT findings. J Korean Radiol Soc. 2001. 45:29–34.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download