Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the clinical characteristics and risk factors of severe manifestation of herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis using medical records from 106 patients diagnosed with herpes zoster ophthalmicus from January 2012 to June 2015. Patients were classified according to the type and frequency of ophthalmologic manifestations. Patients with conjunctivitis, punctate keratitis, and pseudodendritic keratitis were classified into the mild group, whereas patients with deep stromal keratitis, endothelitis, scleritis, glaucoma, and extraocular muscle paralysis were classified into the severe group. The age, sex, severity, location of skin lesions, delayed time to treatment, the presence of Hutchinson's sign, and associated systemic diseases were compared between the groups. In addition, we investigated changes in vision, intraocular pressure, treatment duration, recurrence and the prevalence of postherpetic neuralgia.

Results

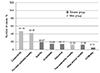

The incidence of conjunctivitis (47.2%), punctate keratitis (42.5%), pseudodendritic keratitis (12.2%), deep stromal keratitis (12.2%), endothelitis (15.1%), scleritis (18.9%), glaucoma (14.2%), and extraocular muscle (EOM) paralysis (4.7%) were observed in these patients. The group with mild disease included 70 cases with conjunctivitis, punctate keratitis and pseudodendritic keratitis. The severe group included 36 cases with deep stromal keratitis, endothelitis, scleritis, glaucoma and EOM palsy. Disease most often occurred in the distribution of the first branch of the trigeminal nerve, with no differences in the age or sex of patients in both groups. Severe manifestations were more common when a greater extent of the skin was involved, when Hutchinson's sign was present, or when treatment was significantly delayed. There were no significant differences between the two groups in recurrence or the presence of postherpetic neuralgia.

Conclusions

Long-term treatment for herpes zoster opthalmicus is more likely to be required if severe manifestation of disease exists, such as widespread skin involvement, Hutchinson's sign, or a delay to the initiation of antiviral treatment. More active observation and treatment are required in such cases.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Frequency of ocular manifestation in patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus (n = 106). The incidende of conjunctivitis and punctate epithelial keratitis was 47% and 42%, respectively. The other diseases was found to be 10% to 20%. EOM palsy was the lowest at 4.72%.EOM = extraocular muscle. |

Table 1

Demographics and clinical characteristics of herpes zoster ophthalmicus patients in the mild and severe groups

References

1. Zaal MJ, Volker-Dieben HJ, D'Amaro J. Visual prognosis in immunocompetent patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003; 81:216–220.

2. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster virus infection. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004; 15:531–536.

3. Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965; 58:9–20.

4. Weinberg JM. Herpes zoster: epidemiology, natural history, and common complications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007; 57:6 Suppl. S130–S135.

5. Arvin AM. Varicella-zoster virus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996; 9:361–381.

6. Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115:2 Suppl. S3–S12.

7. Ostler HB, Thygeson P. The ocular manifestations of herpes zoster, varicella, infectious mononucleosis, and cytomegalovirus disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 1976; 21:148–159.

8. Edgerton AE. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus: report of cases and a review of the literature. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1942; 40:390–439.

9. Kaufman SC. Anterior segment complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115:2 Suppl. S24–S32.

10. Sanjay S, Huang P, Lavanya R. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2011; 13:79–91.

11. Zaal MJ, Völker-Dieben HJ, D'Amaro J. Prognostic value of Hutchinson's sign in acute herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003; 241:187–191.

12. Harding SP, Lipton JR, Wells JC. Natural history of herpes zoster ophthalmicus: predictors of postherpetic neuralgia and ocular involvement. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987; 71:353–358.

13. Tran KD, Falcone MM, Choi DS, et al. Epidemiology of herpes zoster ophthalmicus: recurrence and chronicity. Ophthalmology. 2016; 123:1469–1475.

14. Shaikh S, Ta CN. Evaluation and management of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Am Fam Physician. 2002; 66:1723–1730.

15. Anderson E, Fantus RJ, Haddadin RI. Diagnosis and management of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Dis Mon. 2017; 63:38–44.

16. Marsh RJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. J R Soc Med. 1997; 90:670–674.

17. Marsh RJ, Cooper M. Ophthalmic herpes zoster. Eye (Lond). 1993; 7(Pt 3):350–370.

18. Opstelten W, Zaal MJ. Managing ophthalmic herpes zoster in primary care. BMJ. 2005; 331:147–151.

19. Lee HJ, Kim SY, Jung MS. The clinical characteristics of facial herpes zoster in Korean patients. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2010; 51:8–13.

20. Nithyanandam S, Stephen J, Joseph M, Dabir S. Factors affecting visual outcome in herpes zoster ophthalmicus: a prospective study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010; 38:845–850.

21. Dworkin RH, Portenoy RK. Proposed classification of herpes zoster pain. Lancet. 1994; 343:1648.

22. Stankus SJ, Dlugopolski M, Packer D. Management of herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Am Fam Physician. 2000; 61:2437–2444. 2437–2444.

23. Chung YR, Chang YH, Kim DH, Yang HS. Ocular manifestations of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2010; 51:164–168.

24. España A, Redondo P. Update in the treatment of herpes zoster. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2006; 97:103–114.

25. Jude E, Chakraborty A. Images in clinical medicine. Left sixth cranial nerve palsy with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:e14.

26. Shin MK, Choi CP, Lee MH. A case of herpes zoster with abducens palsy. J Korean Med Sci. 2007; 22:905–907.

27. Sodhi PK, Goel JL. Presentations of cranial nerve involvement in two patients with Herpes zoster ophthalmicus. J Commun Dis. 2001; 33:130–135.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download