Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the neuro-ophthalmic diagnosis and clinical manifestations of intracranial aneurysm.

Methods

A retrospective survey of 33 patients who were diagnosed with intracranial aneurysm and underwent neuro-ophthalmic examination from April 2008 to December 2016. Frequency of the first diagnosis of intracranial aneurysm in ophthalmology, neuro-ophthalmic diagnosis, location of intracranial aneurysm, examination of intracranial aneurysm rupture, and neurologic prognosis of Terson's syndrome patients were analyzed by image examination, neurosurgery, and ophthalmology chart review.

Results

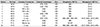

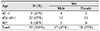

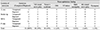

Of the 33 patients, most patients (n = 31, 94%) were diagnosed with intracranial aneurysm at the neurosurgical department and only 2 patients were diagnosed initially at the ophthalmology department. Causes and association were: Terson's syndrome (n = 10, 30%), third cranial nerve palsy (n = 10, 30%), internclear ophthalmoplegia (n = 4, 12%), visual field defect (n = 3, 9%), optic atrophy (n = 3, 9%), sixth cranial nerve palsy (n = 2, 6%), and nystagmus (n = 1, 3%). The location of intracranial aneurysms were: anterior communicating artery (n = 13, 39%), medial communicating artery (n = 12, 36%), and posterior communicating artery (n = 5, 15%). Ten of 33 patients had Terson's syndrome, and 6 patients (60%) with Terson's syndrome had apermanent neurological disorder such as agnosia, gait disorder and conduct disorder.

Conclusions

Third cranial nerve palsy was the most common neuro-ophthalmic disease in patients presenting with intracranial aneurysm. The neuro-ophthalmic prognoses for those diseases were relatively good, but, if Terson's syndrome was present, neurological disorders (agnosia, gait disorder, conduct disorder) were more likely to remain after treatment.

Figures and Tables

Table 4

The analysis of Terson's syndrome patients

BCVA = best corrected visual acuity; M = male; F = female; A com = anterior communicating artery; ICH = intracranial hemorrhage; IVH = intraventricular hemorrhage; OD = oculus dexter; HM = hand motion; SAH = subarchnoid hemorrhage; MCA = medial communicating artery; Rt. = right; OS = oculus sinister; OU = oculus uterque; Lt. = left.

References

1. Ronkainen A, Miettinen H, Karkola K, et al. Risk of harboring an unruptured intracranial aneurysm. Stroke. 1998; 29:359–362.

2. Schievink WI, Mokri B, Piepgras DG. Angiographic frequency of saccular intracranial aneurysms in patients with spontaneous cervical artery dissection. J Neurosurg. 1992; 76:62–66.

3. Vlak MH, Algra A, Brandenburg R, Rinkel GJ. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age, comorbidity, country, and time period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2011; 10:626–636.

4. Purvin VA. Neuro-ophthalmic aspects of aneurysms. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2009; 49:119–132.

5. Schievink WI. Intracranial aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336:28–40.

6. Newman SA. Aneurysms. In : Miller NR, Subramanian P, Patel V, editors. Walsh and Hoyt's Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology: the essentials. 6th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins;2005. p. 2169–2262.

7. Soni SR. Aneurysms of the posterior communicating artery and oculomotor paresis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1974; 37:475–484.

8. Koskela E, Laakso A, Kivisaari R, et al. Eye movement abnormalities after a ruptured intracranial aneurysm. World Neurosurg. 2015; 83:362–367.

9. Cruciger MP, Hoyt WF, Wilson CB. Peripheral and midbrain oculomotor palsies from operations for basilar bifurcation aneurysm in a series of 31 cases. Surg Neurol. 1981; 15:215–216.

10. Laun A, Tonn JC. Cranial nerve lesions following subarachnoid hemorrhage and aneurysms of the circle of Willis. Neurosurg Rev. 1988; 11:137–141.

11. Collins TE, Mehalic TF, White TK, Pezzuti RT. Trochlear nerve palsy as the sole initial sign of an aneurysms of the superior cerebellar artery. Neurosurgery. 1992; 30:258–261.

12. Keane JR. Fourth nerve palsy: historical review and study of 215 inpatients. Neurology. 1993; 43:2439–2443.

13. Koskela E, Setälä K, Kivisaari R, et al. Neuro-ophthalmic presentation and surgical results of unruptured intracranial aneurysm-prospective Helsinki experience of 142 patients. World Neurosurg. 2015; 83:614–619.

14. Pedersen RA, Troost BT. Abnormalities of gaze in cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 1981; 12:251–254.

15. Maramarrom BV, Wijdicks EF. Dorsal mesencephalic syndrome and acute hydrocephalus after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2005; 3:57–58.

16. Day AL. Aneurysms of the ophthalmic segment. A clinical and anatomical analysis. J Neurosurg. 1990; 72:677–691.

17. Date I, Asari S, Ohmoto T. Cerebral aneurysms causing visual symptoms: their features and surgical outcome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1998; 100:259–267.

18. Brown RD Jr, Broderick JP. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: epidemiology, natural history, management options, and familial screening. Lancet Neurol. 2014; 13:393–404.

19. Schultz PN, Sobol WM, Weineist TA. Long-term visual outcome in Terson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1991; 98:1814–1819.

20. Kuhn F, Morris R, Witherspoon CD, Mester V. Terson syndrome. Results of vitrectomy and the significance of vitreous hemorrhage in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 1998; 105:472–477.

21. Walsh FB, Hedges TR. Optic nerve sheath hemorrhage. Am J Ophthalmol. 1951; 34:509–527.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download