Abstract

Purpose

To characterize the development of glaucoma, age of glaucoma onset, and treatments for patients with a facial port-wine stain (PWS).

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of the medical records of 58 patients (116 eyes) with facial PWS between January 2000 and August 2016. We noted patients' age at the initial examination, cup-to-disc ratio, corneal diameter, occurrence of ocular hypertension, development of glaucoma, age of glaucoma onset, and treatments. We compared the clinical features of eyes that developed glaucoma with those that did not develop glaucoma. Among those eyes with glaucoma, we investigated the differences between eyes that underwent surgery and those that did not undergo surgery.

Results

Among the 58 patients with a facial PWS (116 eyes), glaucoma was diagnosed in 38 patients (46 eyes; 39.66%). Of these, 26 patients (27 eyes; 58.69%) underwent glaucoma surgery. PWS-associated glaucoma usually developed by the age of 2 years (85.61%). In all patients, glaucoma developed on the same side of the face as the PWS. Of the 58 patients, 19 (32.76%) showed neurological symptoms, including seizures, developmental delays, intellectual disabilities, or hemiplegia, and 32 (55.17%) were diagnosed with Sturge-Weber syndrome. The mean number of glaucoma surgeries was 1.55 ± 0.93. The initial surgery included trabeculectomy (7 eyes), trabeculotomy (5 eyes), combined trabeculotomy/trabeculectomy (13 eyes), and aqueous drainage device insertion (2 eyes). The mean age at the first surgery was 35.14 ± 50.91 months. In 18 of 27 eyes (66.67%), the postoperative intraocular pressure (IOP) was controlled to below 21 mmHg, but 9 eyes (33.33%) showed elevated IOP and required a reoperation.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Sturge-Weber syndrome patient who underwent trabeculectomy (patient 6). (A) Distribution of left-sided facial port-wine stain that does not cross the midline, and left-sided glaucoma. (B) One-week postoperative appearance. Mildly engorged conjunctival and episcleral vessels with hypovascular bleb. (C) Optic disc photography revealing deep cupping with a cup/disc ratio of 0.9 in the left eye compared to right eye. |

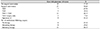

Table 2

Clinicopathological characteristics summarized by eyes of patients with PWS (n = 116)

Values are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. ‘P1’ means ‘comparison between 1 & 2 & 3 (analysis of variance [ANOVA])’, and ‘P2’ means ‘*Comparison between 1 and 2 by post hoc test; †Comparison between 1 and 3 by post hoc test; ‡Comparison between 2 and 3 by post hoc test’.

PWS = port wine stain; C/D = cup/disc; IOP = intraocular pressure.

References

1. Khaier A, Nischal KK, Espinosa M, Manoj B. Periocular port wine stain: the great ormond street hospital experience. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:2274–2278.e1.

2. Dutkiewicz AS, Ezzedine K, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. A prospective study of risk for Sturge-Weber syndrome in children with upper facial port-wine stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015; 72:473–480.

3. Ch'ng S, Tan ST. Facial port-wine stains - clinical stratification and risks of neuro-ocular involvement. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008; 61:889–893.

4. Sullivan TJ, Clarke MP, Morin JD. The ocular manifestations of the Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1992; 29:349–356.

5. Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Syed S, Harper JI. Bilateral facial capillary malformation associated with eye and brain abnormalities. Arch Dermatol. 2006; 142:994–998.

6. Hofeldt AJ, Zaret CR, Jakobiec FA, et al. Orbitofacial angiomatosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979; 97:484–488.

7. Iwach AG, Hoskins HD Jr, Hetherington J Jr, Shaffer RN. Analysis of surgical and medical management of glaucoma in Sturge-Weber syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1990; 97:904–909.

8. Hennedige AA, Quaba AA, Al-Nakib K. Sturge-Weber syndrome and dermatomal facial port-wine stains: incidence, association with glaucoma, and pulsed tunable dye laser treatment effectiveness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008; 121:1173–1180.

9. Ong T, Chia A, Nischal KK. Latanoprost in port wine stain related paediatric glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003; 87:1091–1093.

10. Kim SU, Kim YZ, Hong YJ, Kim HB. A case of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1981; 22:273–276.

11. Chung I, Jang SG, Lew HM. A case of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1986; 27:723–728.

12. Choi JS, Yi KP, Hong KY. A case of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1989; 30:459–464.

13. Chung IH, Kim MH. Sturge-Weber syndrome with congenital ocular anomaly. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1995; 36:2266–2270.

14. Lee H, Choi SS, Kim SS, Hong YJ. A case of glaucoma associated with Sturge-Weber syndrome and Nevus of Ota. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2001; 15:48–53.

15. Kim JW, Park CH, Lee CH. Clinical experience of treatment in a case of Sturge-Weber syndrome with bilateral glaucoma. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1996; 37:908–912.

16. Bae JH, Cho HD, Woo SC. Serous retinal detachment following trabeculectomy in a case of Sturge-Weber syndrome with glaucoma. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1996; 37:2150–2153.

17. Lee SH, Jung DY. Choroidal effesuion after trabeculectomy in glaucoma with Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1999; 40:1164–1168.

18. Yuen NS, Wong IY. Congenital glaucoma from Sturge-Weber syndrome: a modified surgical approach. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2012; 26:481–484.

19. Park JH, Lim SH, Cha SC. Clinical features and surgical outcomes of Sturge-Weber syndrome with glaucoma. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2013; 54:1737–1747.

20. Sharan S, Swamy B, Taranath DA, et al. Port-wine vascular malformations and glaucoma risk in Sturge-Weber syndrome. J AAPOS. 2009; 13:374–378.

21. Parsa CF. Sturge-weber syndrome: a unified pathophysiologic mechanism. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2008; 10:47–54.

22. Miller SJ. Symposium: the Sturge-Weber syndrome. Proc R Soc Med. 1963; 56:419–421.

23. Mantelli F, Bruscolini A, La Cava M, et al. Oculr manifestations of Sturge-Weber syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016; 10:871–878.

24. Dorairaj S, Ritch R. Encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis (Sturge-Weber syndrome, Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber Syndrome): a review. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2012; 1:226–234.

25. Tallman B, Tan OT, Morelli JG, et al. Location of port-wine stains and the likelihood of ophthalmic and/or central nervous system complications. Pediatrics. 1991; 87:323–327.

26. Patient perspectives. what is a port-wine stain (also known as a port-wine birthmark). Pediatr Dermatol. 2016; 33:447–448.

27. Enjolras O, Riche MC, Merland JJ. Facial port-wine stains and Sturge-Weber syndrome. Pediatrics. 1985; 76:48–51.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download