Abstract

Purpose

Methods

Results

Conclusions

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Fundus photography of a patient who was diagnosed with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and latent autoimmune diabetes in adult. A 39-year-old female patient (Patient No.1) presented with decreased visual acuity in the right eye. (A) The patient underwent pars plana vitrectomy due to vitreous hemorrhage and subhyaloid hemorrhage in the right eye. (B) Neovascularization (at the disc and elsewhere) and hard exudate were observed in the opposite eye. |

| Figure 2A case of central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) in the right eye (Patient No. 5). Fundus photography and fluorescein angiography of a 46-year-old woman who presented with decreased visual acuity in the right eye. (A) In the fundus photograph, the right eye showed diffuse flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages and cotton wool patches of CRVO. And there was one flame-shaped retinal hemorrhage (black arrow) with cotton wool patch in the left eye and no microaneurysms. (B) However, two microaneurysms (white arrow) are observed in the left eye in the fluorescein angiography. |

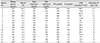

Table 1

Clinical features and characteristics of newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus patients, classified into 3 groups

HTN = hypertension; DM = diabetes mellitus; F = female; M = male; PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy; LADA = latent autoimmune diabetes in adults; NPDR = non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy; CRVO = central retinal vein occlusion; BRVO = branch retinal vein occlusion; CNV = choroidal neovascularization; AMD = age-related macular degeneration; CSC = central serous chorioretinopathy; MH = macular hole.

Table 2

Comparison of diagnosis between both eyes

PDR = proliferative diabetic retinopathy; NPDR = non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy; RRD = rhegmatogenous retinal detachment; CRVO = central retinal vein occlusion; BRVO = branch retinal vein occlusion; DR = diabetic retinopathy; RPE = retinal pigment epithelium; CNV = choroidal neovascularization; AMD = age-related macular degeneration; CSC = central serous chorioretinopathy; MH = macular hole.

Table 3

Diabetic status, lipid profile and renal function test results of the patients

HbA1C = hemoglobin A1C; LDL = low density lipoprotein; TG = triglyceride; Cr = creatinine; GFR = glomerular filtration rate.

*It was measured in the fasting state; †Although HbA1C did not meet the standard of 5.9%, random glucose measured as 205 mg/dL and diagnosed as newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download