Abstract

Background/Aims

Methods

Results

Conclusions

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Flow of the study. Of the 7,178 included subjects, 274 (3.8%) showed an equivocal H. pylori serology test finding. Of the 98 subjects followed-up with an equivocal test finding, 58 (59.2%) showed seroconversion. H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; IgG, immunoglobulin G. |

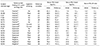

Table 1

Baseline Characteristics of the Followed-up Subjects with an Equivocal H. pylori Test Finding

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori.

ap-values show the differences between 58 subjects with seroconversion and 40 subjects without seroconversion. Continuous variables are shown as mean value±standard deviation using the Student's t-test. Categorical variables are shown in frequency (%) using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test; b≥15 drinks/week for men, ≥8 drinks/week for women.

Table 2

Initial and Follow-up Test Findings of Subjects according to the Follow-up Serum Anti-H. pylori IgG Test Finding

Variables are shown as mean value±standard deviation using the Student's t-test.

H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; IgG, immunoglobulin G; PG, pepsinogen.

ap-values indicate differences between the subjects with seroconversion and without seroconversion; bp-values indicate differences between the initial and follow-up test findings using the signed-rank test.

Table 3

Differences between Subjects with a Negative Test Finding and Those with an Equivocal Test Finding

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or n (%) unless otherwise indicated. Continuous variables are shown as mean value±standard deviation using the Student's t-test. Categorical variables are shown in frequency (%) using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test.

H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; PG, pepsinogen.

Table 4

Findings of Subjects with a History of H. pylori Eradication

Upward arrow (↑) indicates that there was a synchronous increase in serum PG I and PG II levels during the follow-up period, whereas downward (↓) indicates vice versa.

H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; M, male; F, female; PG, pepsinogen.

aSix subjects showed seroconversion at the follow-up test, although the initial serum PG I and PG II levels were low. Most showed decreasing trends of serum PG levels at the follow-up tests, suggesting that seroconversion is related to slow IgG clearance at posteradication period; bThree subjects showed increasing trends of serum PG levels at the follow-up tests, suggesting that there is a reinfection or recrudescence in these subjects; cTwo subjects showed seroreversion despite their high initial serum PG levels. Decreasing trends of serum PG I and PG II levels in these subjects suggest that initial equivocal test findings in these subjects were due to the delayed seroreversion after eradication.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download