Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is characterized by recurrent or chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, which results in increased risk of developing cancer. Anorectal malignant melanoma is often misdiagnosed as either hemorrhoids or benign anorectal conditions in inflammatory bowel disease. Therefore, the overall prognosis and survival of IBD are poor. To date, the best treatment strategy remains controversial. Only early diagnosis and complete excision yield survival benefit. Here, we report a 64-year-old woman with ulcerative colitis, who was found to have anal malignant melanoma on routine colonoscopy. The lesion was confined to the mucosa with no distant metastasis. She underwent complete trans-anal excision. There was no recurrence at the four-year follow-up. Physicians should be aware of increased risk of cancer development in IBD patients and remember the importance of meticulous inspection of the anal canal.

Recurrent or chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract is the main feature of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). This repeated inflammation is one of the key reasons patients with IBD eventually develop cancer.1 Therefore, surveillance colonoscopy is important in the early diagnosis of cancers in order to ensure the best chance for favorable prognosis and survival.

Here, we present a patient with steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis (UC) without specific symptoms, such as pain, bleeding or tenesmus. She was diagnosed with an anal malignant melanoma on routine follow-up colonoscopy. Anorectal malignant melanoma is a rare neoplasm with aggressive features, like local invasion and early metastasis.2 Only early diagnosis of anal malignant melanoma allows for complete excision and favorable prognosis.

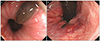

A 64-year-old woman was transferred to Kosin Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinic for frequent defecation of blood-tinged mucoid stool. The initial colonoscopy revealed diffuse erythematous mucosal changes with spontaneous bleeding. She was diagnosed with UC and remained in remission with a regimen of mesalazine and steroids. However, she was not able to reduce her dose of systemic steroids over time, and ultimately was diagnosed with steroid-dependent UC. Low-dose azathioprine was added to maintain remission without steroids. In the third year of our management, a tiny black mucosal lesion was noted at the anal canal on routine follow-up colonoscopy (Fig. 1A, B). Colonoscopic biopsy results revealed malignant melanoma with brown-pigmented tumor nests limited to the surface the squamous epithelium and mucosa.

There was no lymph node or distant metastasis on the chest computed tomography (CT), abdominal CT or positron emission tomography-CT scan. Trans-anal excision was performed successfully. Histopathologic examination revealed both nuclear pleomorphism and cytoplasmic melanin pigmentation in the resected specimen (Fig. 2A, B). Immunochemical staining was positive for both S-100 and HMB45 (Fig. 2C, D). Consequently, the final diagnosis was consistent with malignant mucosal melanoma. The depth of the primary tumor was 3 mm without evidence of metastasis. The follow-up colonoscopy four years post-surgery revealed a tiny scar at the excision site without tumor recurrence (Fig. 3A, B).

IBD is a chronic, recurrent inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract. Many studies have reported that IBD has become more common in Asia over the past few decades, with UC being more common than Crohn's disease (CD). Recently, the incidence of CD has increased in Eastern Asia, including Korea.3 Patients with IBD have an increased risk of intestinal and extra-intestinal malignancy; this risk is attributed to recurrent inflammation and immune dysfunction.1 Advances in pathophysiologic understanding have enabled the development of treatment strategies for IBD patients. Consequently, many immunomodulatory drugs and anti-tumor necrosis factor-related agents have been introduced. However, certain therapeutic agents may hinder the immune surveillance system or cause direct injury to host DNA. Therefore, previous articles reported treatment-related cancer.4

Anal dysplasia, a precursor for anal cancer, is found more frequently in immunocompromised patients, such as those with human immunodeficiency virus, transplanted organ(s), and IBD.5 As mentioned above, IBD patients with frequent exposures to immunosuppressive drugs are at increased risk of developing dysplasia and malignancy in the gastrointestinal tract. In practice, the incidence of anal squamous cell carcinoma, which is a rare disease entity, seems to be increased in CD.6

IBD is one of the risk factors for melanoma. Singh et al. reported a 37% increased risk of melanoma in their systematic review and meta-analysis, which included 12 studies and 172,837 patients.7 Disease duration and extent are the most important risk factors for cancer development.8 Our patient had a disease duration of less than 5 years. Therefore, we were unable to discover any association between occurrence of malignant melanoma and duration of UC. Additionally, we administered thiopurine in an attempt to discontinue her steroids. However, it has been reported that thiopurine administration in UC increases the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer, not melanoma.9 Consequently, there does not appear to be any strong relationship between melanoma development and UC itself or medications in this case. This patient has been continued on the same dose of azathioprine and mesalazine since her operation.

Anorectal malignant melanoma is very rare. Early diagnosis and complete surgical resection are important for long-term survival.10 Patients with IBD need regular surveillance colonoscopy, not only to evaluate their disease status, but also to identify dysplasia or malignant lesions in the colon and anorectum. With routine follow-up colonoscopy, our patient was diagnosed with anal malignant melanoma at a very early stage. Trans-anal excision was sufficient to remove the malignant melanoma. Consequently, there was no recurrence at the four-year follow-up.

Surveillance colonoscopy in IBD patients is essential and should be performed regularly. Close inspection of the intestinal tract enables the early diagnosis of a malignancy with a better chance of the favorable prognosis. As in our case, even highly aggressive malignant melanoma can be managed successfully if an early diagnosis is made by routine colonoscopy. Physicians should bear in mind that the surveillance colonoscopy must be performed thoroughly and that the anal canal also be inspected meticulously.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Initial colonoscopic findings. (A) At one o'clock direction, a black longitudinal lesion (0.8×0.3 cm) without epithelial break was noted in the anal canal. (B) At seven o'clock direction, a similar sized, ovoid, black lesion was noted within the dentate line.

References

1. Kappelman MD, Farkas DK, Long MD, et al. Risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a nationwide population-based cohort study with 30 years of follow-up evaluation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 12:265–273.e1.

2. Pei W, Zhou H, Chen J, Liu Q. Treatment and prognosis analysis of 64 cases with anorectal malignant melanoma. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2016; 19:1305–1308.

3. Ng WK, Wong SH, Ng SC. Changing epidemiological trends of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Intest Res. 2016; 14:111–119.

4. Garg SK, Loftus EV Jr. Risk of cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: going up, going down, or still the same? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016; 32:274–281.

5. Shah SB, Pickham D, Araya H, et al. Prevalence of anal dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 13:1955–1961.e1.

6. Slesser AA, Bhangu A, Bower M, Goldin R, Tekkis PP. A systematic review of anal squamous cell carcinoma in inflammatory bowel disease. Surg Oncol. 2013; 22:230–237.

7. Singh S, Nagpal SJ, Murad MH, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased risk of melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 12:210–218.

8. Kim ER, Chang DK. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: the risk, pathogenesis, prevention and diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:9872–9881.

9. Abbas AM, Almukhtar RM, Loftus EV Jr, Lichtenstein GR, Khan N. Risk of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer in ulcerative colitis patients treated with thiopurines: a nationwide retrospective cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 109:1781–1793.

10. Cheung MC, Perez EA, Molina MA, et al. Defining the role of surgery for primary gastrointestinal tract melanoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008; 12:731–738.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download