Abstract

The peritoneum is one of the common extrapulmonary sites of tuberculosis infection. Patients with underlying end-stage renal or liver disease are frequently complicated by tuberculous peritonitis; however, the diagnosis of the tuberculous peritonitis is difficult due to its insidious nature, well as its variability in presentation and limitation of available diagnostic tests. Once diagnosed, the preferred treatment is usually antituberculous therapy in uncomplicated cases. However, surgical treatment may also be required for complicated cases, such as small bowel obstruction or perforation. An 85-year-old woman was referred our hospital for abdominal pain with ileus. Despite medical therapy, prolonged ileus and progression to sepsis were shown, she underwent surgery to confirm the diagnosis and relief of mechanical ileus. Intraoperative peritoneal biopsy and macroscopic findings confirmed tuberculous peritonitis. Therefore, physicians should consider the possibility of tuberculous peritonitis in patients with unexplained small bowel obstruction.

Tuberculosis is usually seen as pulmonary tuberculosis. However, it may also involve other various extrapulmonary organs. The peritoneum is a relatively common extrapulmonary site for tuberculosis. Peritoneal involvement accounts for 0.1-0.7% of all tuberculous patients.1 Patients with tuberculous peritonitis present insidious nature and nonspecific symptoms that make diagnosis difficult, and intestinal obstruction or perforation, which may require surgery, rarely occurs in patients with tuberculous peritonitis.2 We report a rare case of tuberculous peritonitis that was diagnosed after surgical treatment due to progressive sepsis seen in a patient who visited our hospital due to intestinal obstruction.

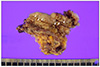

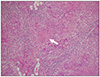

An 85-year-old woman was transferred from a local hospital for an evaluation of abdominal bloating under suspicion of ileus. Except for hypertension, she had no remarkable medical history and no prior abdominal surgery. The patient had experienced difficulty with defecation for several months. Three days before admission, she developed abdominal distension with marked constipation. At the time of admission, vital signs were as follows: temperature of 37.1℃, pulse of 112 beats per minute, and blood pressure of 145/90 mmHg. Electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia. Physical examination revealed abdominal distension with whole abdominal mild tenderness. A step ladder sign was shown on abdominal X-ray with distended bowel loop (Fig. 1). There was no specific abnormal finding on the chest X-ray. Small amount of ascites and diffuse dilation of small bowel were identified on the computed tomography (CT), but transitional point of obstructive lesion could not be found by the CT scan (Fig. 2). Blood test results were as follows: total leukocytes of 15,630/µL (polymorphonuclears 78.2%), hemoglobin of 11.3 g/dL, C-reactive protein of 25.12 mg/dL, and albumin of 2.5 g/dL. The results of viral markers were negative for hepatitis B and C. Initially, parenteral therapy was started with hydration and antibiotics in the intensive care unit, while waiting for symptoms to improve. Within the first five days after admission, she had recurrent fever and hypotension with persistent ileus. Therefore, the patient underwent emergency exploratory laparoscopy. Surgical findings showed that numerous whitish fine nodules were diffusely distributed throughout the peritoneum and omentum. In addition, adhesions between the terminal ileum and the pelvic cavity, which were the cause of obstruction and marked dilatation of proximal small intestine, were identified. Around the ovaries, multiple nodules were also observed, and a moderate amount of turbid and yellowish brown ascites was discovered. Switched to laparotomy, peritoneal biopsy, ileostomy, and left salpingo-oophorectomy were performed. According to the gross pathology report, numerous grey-whitish nodules were identified on the external surface of the omentum (Fig. 3). Pathologic report revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation with central necrosis of the ovary, omentum, and peritoneum, consistent with tuberculous peritonitis (Fig. 4). Two weeks later, antituberculous regimen, which consisted of isoniazid (INH), rifampicin (RIF), pyrazinamide (PZA), and ethambutol (EMB), was started. In a month, she was discharged with good response to medical therapy, and she is currently under observation.

Abdominal tuberculosis may involve the gastrointestinal tract, mesenteric lymph nodes, and peritoneum. Recently, the incidence has been increasing globally due to increased number of immunocompromised patients and free immigrants worldwide; however, tuberculous peritonitis is still a rare occurrence in developed countries.3

Tuberculosis can affect the peritoneum in several ways. Infection occurs most commonly following a reactivation of latent tuberculous foci in the peritoneum via a hematogenous spread from a primary lung focus.2 It can also occur via a hematogenous spread from an active pulmonary or miliary tuberculosis. Much less frequently, the organisms enter the peritoneal cavity by transmurally from an infected small intestine or by contiguously from tuberculous salpingitis.4

Tuberculous peritonitis is a subacute disease. Its symptoms evolve over a period of several weeks to months. In many cases, its comorbid situations and insidious nature make the diagnosis very difficult, which results in delayed treatment. More than 90% of patients have ascites with symptoms, and it is difficult to differentiate them from bacterial peritonitis due to underlying liver disease or end-stage renal disease. Cavalli et al.5 suggested that the most common features of tuberculous peritonitis were abdominal pain, fever, ascites, or abdominal swelling, while abdominal mass or salpingitis might also be shown. According to some other studies, common features include ascites, low grade fever, weight loss with vague abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly. Rarely, intestinal obstruction can occur due to intestinal loop, intestinal, and mesenteric adhesions.

The insidious nature of this disease makes the diagnosis a clinical challenge; therefore, it is important to suspect tuberculous peritonitis in patients with ascites. The gold standard for diagnosis is taking a culture of the mycobacterium in ascitic fluid or peritoneum. However, this microbiologic diagnosis requires 4-8 weeks by conventional media. As an initial test, paracentesis can be helpful. In the peritoneal fluid analysis, the majority of patients show leuckocytosis with a relative pleocytosis, and the serum-ascites albumin gradient is <1.1 g/dL.67 Imaging studies are also useful, including ultrasonography and CT. Ultrasonography is useful for the observation of multiple fine septations, which are characteristiccally found in tuberculous peritonitis, while CT can detect the peritoneal, mesenteric and omental involvement.89 They are complementary to each other. Laparoscopy is the diagnostic tool that makes histological study of specimens possible. Moreover, macroscopic diagnosis is also possible by inspecting the peritoneum. The sensitivity and specificity rates are impressively high when the macroscopic appearances are combined with the histological findings.1 In the current case, we tried to conduct the abdominal paracentesis for inspection of ascitic fluid. Unfortunately, the volume of ascites was small, and the risk of bowel perforation was high due to distended bowel; thus, the abdominal paracentesis could not be performed.

The main treatment option for tuberculous peritonitis is pharmalogical therapy. The regimens curative for pulmonary tuberculosis are also effective for tuberculous peritonitis. A 2 months initial phase of INH, RIF, PZA, and EMB, followed by the administrations of INH and RIF for another 4 months, may be sufficient in most cases of tuberculous peritonitis. Streptomycin might be considered a first-line medication. Demir et al.10 reported that triple therapy without RIF for 6 months was sufficient in treating tuberculous peritonitis. In their study, 24 patients were treated for 6 months with INH, streptomycin (total dose 40 g), and PZA (for the first 2 months and then substituted with EMB). Usually, basic regimens are curative, but delay in diagnosis, drug resistance, and comorbid conditions may lead to significantly poor prognosis. Acute abdomen has been reported in patients with abdominal tuberculosis, mainly resulting from ileus or bowel perforation.11 In such cases, an exploratory laparotomy is important for the diagnosis of disease and improvement of prognosis.

In our case, undiagnosed tuberculous peritonitis resulted in mechanical ileus. In spite of medical treatment, clinical aggravation led to urgent exploratory laparoscopy. Intraoperative findings revealed a small amount of ascites, diffuse fibroadhesive change of the peritoneum, and obstruction in the terminal ileum due to adhesions. Therefore, a conversion to laparotomy and surgical treatment to the obstructive lesion were done. Administration of antituberculous regimen was started after the operation. Tuberculous peritonitis was established pathologically and the patient showed improvement.

In conclusion, tuberculous peritonitis accounts for a small portion of all tuberculous cases, but it has been increasing worldwide, including developed countries. Early suspicion of the disease is important because the symptoms of tuberculous peritonitis are vague and has a subacute nature. In rare cases, small bowel obstruction or perforation may be combined, leading to the need for surgical treatment. Exploratory laparoscopy or laparotomy is not only a diagnostic tool, but it can also be a method of treatment. Early antituberculous therapy should begin in the presence of suspicious intraoperative findings, despite the establishment of microbiologic or microscopic diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Abdominal X-ray at admission. Distended bowel loop of small bowel and fluid level in erect (A) and supine (B) view.

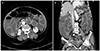

Fig. 2

Abdominal computed tomography showing ascites and diffuse dilation of small bowel but collapsed colon in transverse (A) and coronal (B) view.

References

1. Mehta JB, Dult A, Harvill L, Mathews KM. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis: a comparative analysis with pre-AIDS era. Chest. 1991; 99:1134–1138.

2. Sanai FM, Bzeizi KI. Systemic review: tuberculous peritonitis--presenting features, diagnostic strategies and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005; 22:685–700.

3. Palmer KR, Patil DH, Basran GS, Riordan JF, Silk BD. Abdominal tuberculosis in urban Britain--a common disease. Gut. 1985; 26:1296–1305.

4. Tang LC, Cho HK, Wong Taam VC. Atypical presentation of female genital tract tuberculosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1984; 17:355–363.

5. Cavalli Z, Ader F, Valour F, et al. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and bacterial epidemiology of peritoneal tuberculosis in two university hospitals in France. Infect Dis Ther. 2016; 5:193–199.

6. al-Quorain AA, Facharzt , Satti MB, al-Freihi HM, al-Gindan YM, al-Awad N. Abdominal tuberculosis in Saudi Arabia: a clinicopathological study of 65 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993; 88:75–79.

7. Ilhan AH, Durmuşoğlu F. Case report of a pelvic-peritoneal tuberculosis presenting as an adnexial mass and mimicking ovarian cancer, and a review of the literature. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 12:87–89.

8. Demirkazik FB, Akhan O, Ozmen MN, Akata D. US and CT findings in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis. Acta Radiol. 1996; 37:517–520.

9. Akhan O, Pringot J. Imaging of abdominal tuberculosis. Eur Radiol. 2002; 12:312–323.

10. Demir K, Okten A, Kaymakoglu S, et al. Tuberculous peritonitis--reports of 26 cases, detailing diagnostic and therapeutic problems. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001; 13:581–585.

11. Farantos Ch, Damilakis I, Germanos S, Lagoudellis A, Skaltsas S. Acute intestinal obstruction as the first manifestation of tuberculous peritonitis. Hellenic J Surg. 2013; 85:192–196.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download