Abstract

A Dieulafoy lesion in the rectum is a very rare and it can cause massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding. An 83-year-old man visited our hospital. He had chronic constipation and had taken aspirin for about 10 years because of a previous brain infarction. He was admitted because of a recent brain stroke. On the third hospital day, he had massive hematochezia and suddenly developed hypovolemic shock. Abdominal computed tomography showed active arterial bleeding on the left side of the mid-rectum. Emergency sigmoidoscopy showed an exposed vessel with blood spurting from the rectal wall. The active bleeding was controlled successfully by an injection of epinephrine and two hemoclippings. On the fourth day after the procedure, he had massive recurrent hematochezia, and his vital signs were unstable. Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery band ligation was performed urgently at two sites. However, he rebled on the third postoperative day. Selective inferior mesenteric angiography revealed an arterial pseudoaneurysm in a branch of the superior rectal artery, as the cause of rectal bleeding, and this was embolized successfully. We report a rare case of life-threatening rectal bleeding caused by a Dieulafoy lesion combined with pseudoaneurysm of the superior rectal artery which was treated successfully with embolization.

Rectal bleeding represents 9% to 10% of all causes of lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.1 The most common causes of massive rectal bleeding include hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and fistulas-in-ano. More unusual causes of bleeding include solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, radiation proctitis, and prostate biopsy.2 Massive low GI bleeding is often difficult to diagnose and to manage. A Dieulafoy lesion has been widely described in the stomach, but in the rectum is a very rare entity that can cause massive lower GI bleeding.3 Pseudoaneurysm arising from superior rectal artery is also rare and selective embolization offers a viable option for treatment in patients with massive lower GI bleeding.4 Herein, we report a rare case of life-threatening rectal bleeding that caused by a rectal Dieulafoy leision combined with a pseudoaneurysm of superior rectal artery that was treated successfully with selective arterial pseudoaneurysm embolization.

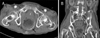

An 83-year-old man had chronic constipation and had taken aspirin for about 10 years because of a previous brain infarction. He was admitted to our hospital because of a recent brain stroke. Aspirin was discontinued and clopidogrel therapy was started. On the third hospital day, he had massive hematochezia and suddenly developed hypovolemic shock. The volume of rectal bleeding was about 1,300 mL. His blood pressure was 80/40 mmHg, pulse rate 134 beats/min, and hemoglobin level 7.7 g/dL. Clopidogrel therapy was discontinued. Initial resuscitation was performed using crystalloid solution and pack red blood cell transfusion. We found only food material via a Levin tube. Abdominal CT angiography showed active arterial bleeding on the left side of the mid-rectum (Fig. 1). Emergency sigmoidoscopy showed an exposed vessel with blood spurting from the rectal wall without mucosal defect, which was consistent with Dieulafoy lesion (Fig. 2A). The active bleeding was controlled successfully by injection of epinephrine (8 mL, 1:10,000) and two hemoclippings (Fig. 2B). On the next day, follow-up sigmoidoscopy showed multiple stercoral ulcers with internal hemorrhoid but with no more bleeding (Fig. 2C).

On the fourth day after the procedure, he had massive recurrent hematochezia and his vital signs were unstable. His blood pressure was 86/62 mmHg, and hemoglobin level 8.6 g/dL. Emergency sigmoidoscopy showed an exposed vessel with blood spurting from the rectal wall. After injection of epinephrine (5 mL, 1:10,000) and one hemoclipping, the active bleeding was not controlled. The patient was transferred to general surgery for an emergency hemorroidectomy because the bleeding could be possible from the internal hemorrhoid. Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery band ligation was performed urgently at two sites.

On the third postoperative day, rebleeding occurred. Selective inferior mesenteric arteriography revealed an arterial pseudoaneurysm in a branch of the superior rectal artery. Concerned about complicating the ischemic proctitis, we superselectively embolized the pseudoaneurysm with a gelatin sponge pledget as a temporary embolic agent. Three days after the embolization, he had massive recurrent hematochezia. Emergency selective inferior mesenteric arteriography revealed that the previously noted arterial pseudoaneurysm in the superior rectal arterial branch had increased in size and active pseudoaneurysmal bleeding was noted. We superselectively embolized it successfully with n-butyl cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl®; B. Broun, Melsurgen, Germany), a permanent embolic agent (Fig. 3). He was finally stable without further bleeding.

Acute massive GI bleeding involves symptoms of hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia that causes hemodynamic instability (hypotension with systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg) or required transfusion of at least four units of blood within 24 hours of symptoms of acute bleeding.5 Massive low GI bleedings are often difficult diagnostically and in terms of management. Although rare, Dieulafoy lesions need to be considered in the differential diagnosis of major rectal bleeding, particularly as they are often suitable for endoscopic therapy.6 Rectal Dieulafoy lesions have been associated with advanced age, renal failure, burns, liver transplantation and GI stromal tumors, but not with other type of tumors.3 The Dieulafoy lesion is an unique vascular malformation, consisting of a tortuous long vessel, located in the submucosa, causing a small lesion in the overlying mucosa.3

Pseudoaneurysms can be life-threatening due to rupture and bleeding. Therefore, pseudoaneurysms are considered an emergency disease and need to be diagnosed accurately and quickly.7 Causes of pseudoaneurysm are iatrogenic complication, trauma, injury by tumor, infection, vasculitis and inflammation.7 Visceral Pseudoaneurysms are uncommon and rare entities.8 The splenic artery is the most commonly affected visceral artery and they usually develop secondary to pancreatitis.8 In our patients, the cause of superior rectal artery pseudoaneurysm is rectal Dieulafoy lesion. Bleeding diathesis due to antithrombotic agent, chronic constipation and stercoral ulcers might be aggravating factor of massive lower GI bleeding.

For patients with a history of coagulopathy, anticoagulants or antiplatelet therapy should correct clotting deficiencies.9,10 Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs act by irreversibly inhibiting cyclooxygenase, thereby preventing platelet thromboxane A2 formation.11 To stop massive bleeding, platelets are transfused in patients on antiplatelet agent.10 In this case, the patient had hemorrhagic diathesis caused by aspirin and clopidogrel medication.

A digital rectal examination is used to detect anal pathology.10 Flexible sigmoidoscopy is useful for evaluating the rectal mucosa and determining whether blood is coming from a source proximal to the rectum.10,12 Submucosal injection of epinephrine is the most commonly described endoscopic technique for achieving hemostasis. In addition to the direct vasospasm, there may be a component of tamponade in the hemostatic effects of epinephrine injection, although epinephrine may provide only temporary control of hemorrhage.10 Endoscopic hemostatic clips are used for active bleeding. Hemostatic clips have the advantages of a longer-lasting effect than epinephrine injection and the lack of risk of thermal injury compared with coagulation techniques.10 Endoscopic band ligation is a standard treatment in esophageal varix bleeding,13 and has been used recently for the endoscopic treatment of bleeding rectal varices and rectal Dieulafoy lesion.13-15 Endoscopic rubber band ligation of a hemorrhoid is considered a useful and safe technique,14 although a few cases of delayed massive rebleeding have been reported after endoscopic rubber band ligation.16,17 In our patient, we tried epinephrine injection with two hemoclippings, which seemed to be effective at first. However, another bleeding episode occurred four days later, and we decided to operate to provide a complete resolution, because rectal Dieulafoy lesion was confused with internal hemorrhoidal bleeding at that time.

Large pseudoaneurysm can be detected easily on contrast-enhanced CT, whereas small lesions can be overlooked easily. In such cases, angiography is required.7 The vascular blood supply to the rectum is from a relatively rich anastomotic supply the inferior mesentery artery via the superior rectal artery and the middle and inferior rectal arteries that arise as branches of the internal iliac artery and supply the lower one-half to two-thirds of the rectum.4 The collateral blood supply allows a safety margin during embolization to prevent ischemia or infarction, which can occur during colonic or small bowel embolization.18 The right and left inferior rectal artery are distal branches of the internal pudendal artery within the ischiorectal fossa. These arteries have an extensive anastomotic network within the wall of the rectum. The goal of embolization therapy should be to decrease the pulse pressure at the bleeding site to allow for hemostasis.2 The major risk of embolization is bowel ischemia,18 which is why we did not perform embolization as the first procedure. Superselective, distal embolization would be expected to minimize that risk.4 Increasing evidence supports the theory that superselective embolization is more efficacious in reducing complications. Diagnostic angiography, with a view to superselective embolization if the sigmoidoscopy fails to localize and treat the cause of hemorrhage, obviating the need for repeated endoscopy or emergency surgery.19

In our case, we report on a patient with massive lower GI bleeding that required frequent endoscopic intervention, surgical hemorrhoidal artery ligation, and two applications of angiographic embolization. An endoscopic diagnosis of rectal Dieulafoy lesions is not always easy, because the lesions are very small, and there are usually clots or stools in the rectum.20 Angiography allows confirmation of site of pseudoaneurysm and the pseudoaneurysm of the superior rectal artery was successfully treated with superselective embolization without rectal ischemia. To best of our knowledge, this case is the first report of life-threatening rectal bleeding caused by a Dieulafoy lesion combined with pseudoaneurysm of the superior rectal artery, which was treated successfully with embolization.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Abdominal pelvic CT findings (enhanced image). Contrast-enhanced axial (A) and coronal (B) CT images showing contrast extravasation from the left side wall of the mid-rectum (arrows), which was suggestive of active arterial bleeding. |

| Fig. 2Endoscopic findings. (A) Emergency sigmoidoscopy showed an exposed vessel with blood spurting from the rectal wall with an internal hemorrhoid. (B) The active bleeding was controlled successfully after injection of epinephrine and two hemoclippings. (C) On the next day, follow-up sigmoidoscopy showed multiple stercoral ulcers with internal hemorrhoid but no further bleeding. |

| Fig. 3Angiographic findings. Selective inferior mesenteric arteriography revealed an arterial pseudoaneurysm (A) in a branch of the superior rectal artery, which was the cause of the massive rectal bleeding. It was embolized successfully by superselective embolization with n-butyl cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl®), a permanent embolic agent (B). |

References

1. Lee EW, Laberge JM. Differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004. 7:112–122.

2. Syed MI, Chaudhry N, Shaikh A, Morar K, Mukerjee K, Damallie E. Catheter-directed middle hemorrhoidal artery embolization for life-threatening rectal bleeding. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007. 21:117–123.

3. Ruiz-Tovar J, Díe-Trill J, López-Quindós P, Rey A, López-Hervás P, Devesa JM. Massive low gastrointestinal bleeding due to a Dieulafoy rectal lesion. Colorectal Dis. 2008. 10:624–625.

4. Baig MK, Lewis M, Stebbing JF, Marks CG. Multiple microaneurysms of the superior hemorrhoidal artery: unusual recurrent massive rectal bleeding: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003. 46:978–980.

5. Chang WC, Liu CH, Hsu HH, et al. Intra-arterial treatment in patients with acute massive gastrointestinal bleeding after endoscopic failure: comparisons between positive versus negative contrast extravasation groups. Korean J Radiol. 2011. 12:568–578.

6. Hokama A, Takeshima Y, Toyoda A, et al. Images of interest. Gastrointestinal: rectal Dieulafoy lesion. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005. 20:1303.

7. Sueyoshi E, Sakamoto I, Nakashima K, Minami K, Hayashi K. Visceral and peripheral arterial pseudoaneurysms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005. 185:741–749.

8. Gupta V, Kumar S, Kumar P, Chandra A. Giant pseudoaneurysm of the splenic artery. JOP. 2011. 12:190–193.

9. Ozdil B, Akkiz H, Sandikci M, Kece C, Cosar A. Massive lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage secondary to rectal hemorrhoids in elderly patients receiving anticoagulant therapy: case series. Dig Dis Sci. 2010. 55:2693–2694.

10. Whitlow CB. Endoscopic treatment for lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2010. 23:31–36.

11. Nelson RS, Ewing BM, Ternent C, Shashidharan M, Blatchford GJ, Thorson AG. Risk of late bleeding following hemorrhoidal banding in patients on antithrombotic prophylaxis. Am J Surg. 2008. 196:994–999.

12. Van Rosendaal GM, Sutherland LR, Verhoef MJ, et al. Defining the role of fiberoptic sigmoidoscopy in the investigation of patients presenting with bright red rectal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000. 95:1184–1187.

13. Jang JW, Chae HS, Shin JH, et al. A case of rectal bleeding treated by endoscopic band ligation. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2001. 22:229–232.

14. Lee KW, Chae HS, Park YB, et al. A case of rectal varix bleeding treated with endoscopic variceal ligation. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2003. 26:52–55.

15. Yoshikumi Y, Mashima H, Suzuki J, et al. A case of rectal Dieulafoy's ulcer and successful endoscopic band ligation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006. 20:287–290.

16. Odelowo OO, Mekasha G, Johnson MA. Massive life-threatening lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage following hemorrhoidal rubber band ligation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002. 94:1089–1092.

17. Bat L, Melzer E, Koler M, Dreznick Z, Shemesh E. Complications of rubber band ligation of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993. 36:287–290.

18. Guy GE, Shetty PC, Sharma RP, Burke MW, Burke TH. Acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: treatment by superselective embolization with polyvinyl alcohol particles. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992. 159:521–526.

19. Berczi V, Gopalan D, Cleveland TJ. Embolization of a hemorrhoid following 18 hours of life-threatening bleeding. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008. 31:183–185.

20. Nomura S, Kawahara M, Yamasaki K, Nakanishi Y, Kaminishi M. Massive rectal bleeding from a Dieulafoy lesion in the rectum: successful endoscopic clipping. Endoscopy. 2002. 34:237.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download