Abstract

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a vascular neoplasm, which is fairly prevalent in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients. Mucocutaneous and lymph node involvements are characteristic features of KS in AIDS patients. The involvement of gastrointestinal tract occurs in 40% of KS patients and leads to significant morbidity and mortality. In the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era, the rate of AIDS related KS has fallen with control of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) viremia. However, it is still recognized as the primary AIDS-defining illness, and the proportion of AIDS diagnoses made due to KS ranged from 4.1% to 7.5%. In Korea, AIDS-related KS has been report in low rate incidence. Its gastrointestinal involvements are rarely reported. To date, five cases have been recorded in Korea. Herein, we present an additional case of gastrointestinal KS as the AIDS-defining illness and review of the Korean medical literature.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a vascular tumor involving blood and lymphatic vessels of multifactorial organ. HHV-8, known KS associated herpesvirus, is the important oncogenic factor with cytokine induced growth. There are four groups KS based on the clinical setting; classic KS, endemic KS, acquired KS and epidemic KS.1 Epidemic KS is most common type and an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) related form. Its skin involvement shows the characteristic findings including elliptical purple colored maculopapule. And, the involvement of visceral organ is more common and life-threatening than other types of KS. Half of cutaneous KS have the involvement of internal organ, and extracutaneous involvement can occur without cutaneous manifestations.2

By 1989, 15% of all reported AIDS cases in United States had KS as the primary AIDS-defining illness. In the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era, the incidence of AIDS-related KS are less than 10% of the incidence reported in preHAART era3 but it is still recognized as the primary AIDS-defining illness, and causes the significant morbidity with organ dysfunction.

In Korea, AIDS-related KS have been reported in low rate incidence, 1.1% of AIDS population.4 Its gastrointestinal involvements are rarely reported. To date, five cases have been recorded in Korea.5-9 Herein, we present an additional case of gastrointestinal KS as the AIDS-defining illness and review of the Korean medical literature.

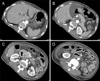

A 60-year-old male was admitted to Chonnam National University Hospital with one month history of exertional dyspnea and chest discomfort. He complained of anorexia, vomiting and weight loss. He denied any previous medical histories. On admission, he had a temperature of 38.4℃, pulse rate of 84 beats/min, blood pressure of 136/76 mmHg and respiratory rate of 22 times/min. The head and neck examination was normal except for anemic conjunctiva. There were many variable sized purple colored patches in his trunk, both extremities and oral cavity (Fig. 1). Inspiratory crackles were checked on both lung fields. The abdomen was moderately distended without tenderness or rebound tenderness. Laboratory studies revealed hemoglobin 9.9 g/dL, hematocrit 29.9%, white blood cell counts 2,390/mm3 with differential count of 58.2% neutrophils and 17.6% lymphocytes, platelet counts of 108,000/mm3, serum albumin 2.3 g/dL, AST 44 U/L, ALT 9 U/L, ALP 71 U/L and CRP 6.0 mg/dL. Coagulation profiles were prothrombin time 16.0 sec (control 11.8 sec), activated partial thromboplastin time 45.9 sec (control from 28 to 40 sec). The serologic tests for hepatitis viruses A, B, and C were negative. A chest CT showed the bilateral ground glass opacity and moderate pleural effusion, but no mediastinal lymphadenopathy, suggestive of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). On his sputum culture, pneumocystis PCR was positive. A abdomen CT showed the multifocal nodular wall thickening from the stomach to jejunum, paraaortic mesenteric lymphadenopathy and large amounts of ascites (Fig. 2).

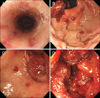

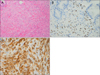

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed the multiple variable sized hyperemic lobulated mass lesions scattered in the esophagus, stomach and duodenum (Fig. 3). Forceps biopsy specimens were taken from the lesions. Microscopic finding of H&E stain revealed the vascular spindle cell proliferation (Fig. 4A). In immunohistochemical examination, tumor cells showed a strong reactivity of HHV-8 and CD31 (Fig. 4B, C). However, immunohistochemical staining for c-kit and s-100 proteins was negative (data not shown). Biopsy specimens were interpreted as KS. He was positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test and his CD4 level was 16 cells/mm3. According to AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) staging system for AIDS-related KS, he was classified into poor risk group, based on tumor extension (T1: visceral organ involvement), immune system status (I1: low CD4 cell count ≤200/µL), HIV-1-associated systemic illness (S1: B symptoms, opportunistic infection, Karnofsky score lower than 70%). Chest x-ray finding was getting better on PCP treatment. HAART was started and systemic chemotherapy (paclitaxel based) was considered for extensive KS. But, on hospital course, he had prolonged pancytopenia and progression of cutaneous KS. On hospital day 21, he expired due to multi-organ failure.

KS developed in less than one percentile of the general population, but AIDS-related KS was estimated 2,000 times greater than that of the general population and 300 times greater that of the other kinds of immunocompromised host, especially homosexual men.10 Although KS primarily manifests as a mucocutaneous lesions, visceral involvement occurs in more than 25% of patients with AIDS-related KS and often symptomless. The common visceral involvements include the stomach, bowel, liver, spleen and lung. Gastrointestinal KS sometimes presents bleeding, obstruction, abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea.11 These gastrointestinal symptoms were mistaken of AIDS related systemic symptoms. Therefore, clinician should consider the possibility of gastrointestinal KS and perform esophagogastroduodenoscopy if patients complain of gastrointestinal symptoms.12

Until now, only 6 cases of gastrointestinal KS including our case have been reported in Korea (Table 1). The patients were aged 32 to 70 years (mean age, 48.3 years), and consisted of all men. Four cases were known homosexuals and two were unknown. Most cases (5 of 6 cases) suffered from gastrointestinal symptoms. Except two cases including ours, four cases were previous known HIV patients. The clinical presentations of KS and PCP led to the diagnosis of AIDS in our case. All cases had mucocutaneous KS lesions and low CD4+ cell count and were classified as poor risk group as ACTG staging system according to tumor extent (T), severity of immunosuppression (I) and other systemic HIV-1-associated illness (S).13 The most common site of gastrointestinal KS was the stomach (all cases), followed by esophagus (4 of 6 cases). Three cases could receive HAART combination therapy with chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Among them, only one case survived and two expired due to pancytopenia and multi-organ failure. In our case, KS was more extensive and progressive. He showed low CD4+ cell count, extracutaneous manifestation, opportunistic infection and low performance status score. In ACTG staging system, his prognostic index revealed poor risk.

Generally, in advanced, symptomatic KS, HAART combination chemotherapy is considered as the first line therapy as palliative rather than curative treatment.14 Recent studies showed that HAART combined with chemotherapy prolonged the time to treatment failure of anti-KS therapies15 and current 2-year survival rates for AIDS-related KS have significantly increased from 35% before 1996 to over 80% at the present time.16 Unfortunately, our case was diagnosed at advanced stage and not tolerable for combination therapy. Half of cases (3 of 6 cases) could not go on therapy because of poor condition at diagnosis.

In summary, early diagnosis and treatment of KS is important for AIDS patient's prognosis. Therefore, the gastrointestinal KS should be considered, in particular, in the differential diagnosis of gastrointestinal symptoms in immunocompromised hosts and perform esophagogastroduodenoscopy if patients complain of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Skin lesions. Various sized violet colored papules were noted at the upper extremity (A) and trunk (B).

Fig. 2

Abdomen CT findings. Abdomen CT finding showed multiple nodular wall thickening in the stomach (A, B) and concentric wall thickening and enhancement in duodenal 2nd to 3rd portion (C) and jejunum (D).

Fig. 3

Endoscopic findings. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed multiple variable sized reddish flat elevated lesions in the esophagus (A), and polypoid masses in the stomach cardia (B), antrum (C) and the duodenal second portion (D).

Fig. 4

Pathologic findings of biopsy specimens. (A) Routine histology showed spindle-shaped cell proliferation, extravasated red blood cells and vascular proliferation (H&E, ×200). (B) Immunostaining was positive for Kaposi sarcoma associated herpesvirus, HHV-8 (×200). (C) Immunostaining is positive for the endothelial marker, CD31 (×200).

References

1. Giraldo G, Beth E, Buonaguro FM. Kaposi's sarcoma: a natural model of interrelationships between viruses, immunologic responses, genetics, and oncogenesis. Antibiot Chemother. 1983. 32:1–11.

2. Arora M, Goldberg EM. Kaposi sarcoma involving the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010. 6:459–462.

3. Jones JL, Hanson DL, Dworkin MS, Jaffe HW. Incidence and trends in Kaposi's sarcoma in the era of effective antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000. 24:270–274.

4. Kim JM, Cho GJ, Hong SK, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical features of HIV infection/AIDS in Koreans. Korean J Med. 2001. 61:355–364.

5. Kim HS, Park HW, Jeon SH, et al. Gastrointestinal Kaposi's sarcoma in an AIDS patient. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2000. 20:a420.

6. Kim SH, Goo JM, Lee JW, Chung MJ, Lee YJ, Im JG. Pulmonary involvement of Kaposi sarcoma in an AIDS patient: radiologic and pathologic findings. J Korean Radiol Soc. 2002. 46:37–40.

7. Moon HS, Park KO, Lee YS, et al. A case of Kaposi's sarcoma of the stomach and duodenum in an AIDS patient. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2003. 27:148–152.

8. Hong KD, Nam SW, Lee SE, et al. A case of Kaposi sarcoma of the bronchi and gastrointestinal tract in an AIDS patient. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2007. 11:157–161.

9. Chung DW, Chang HH, Hwang HY, et al. A case of gastrointestinal Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with AIDS. Korean J Med. 2009. 77:371–375.

10. Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, Jaffe HW. Kaposi's sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990. 335:123–128.

11. Danzig JB, Brandt LJ, Reinus JF, Klein RS. Gastrointestinal malignancy in patients with AIDS. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991. 86:715–718.

12. Dezube BJ, Pantanowitz L, Aboulafia DM. Management of AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma: advances in target discovery and treatment. AIDS Read. 2004. 14:236–238. 243–244. 251–253.

13. Nasti G, Talamini R, Antinori A, et al. AIDS Clinical Trial Group Staging System in the Haart Era--the Italian Cooperative Group on AIDS and Tumors and the Italian Cohort of Patients Naive from Antiretrovirals. AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: evaluation of potential new prognostic factors and assessment of the AIDS Clinical Trial Group Staging System in the Haart Era--the Italian Cooperative Group on AIDS and Tumors and the Italian Cohort of Patients Naive From Antiretrovirals. J Clin Oncol. 2003. 21:2876–2882.

14. Portsmouth S, Stebbing J, Gill J, et al. A comparison of regimens based on non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors or protease inhibitors in preventing Kaposi's sarcoma. AIDS. 2003. 17:F17–F22.

15. Bower M, Fox P, Fife K, Gill J, Nelson M, Gazzard B. Highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) prolongs time to treatment failure in Kaposi's sarcoma. AIDS. 1999. 13:2105–2111.

16. Lodi S, Guiguet M, Costagliola D, Fisher M, de Luca A, Porter K. CASCADE Collaboration. Kaposi sarcoma incidence and survival among HIV-infected homosexual men after HIV seroconversion. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010. 102:784–792.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download