Abstract

We report the rare case of a patient with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) who initially presented to the hospital with symptoms of cardiac failure. Preoperative cardiac studies did not reveal any underlying ischemia. After resection of a large 14-cm left renal tumor, cardiac function was noted to improve dramatically. We discuss this case of concomitant RCC and nonischemic cardiomyopathy.

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common primary tumor of the kidney and often remains clinically indolent, with most lesions picked up incidentally through radioimaging. The classic triad of hematuria, flank pain, and a palpable mass occurs in 20% of patients with RCC, whereas up to 40% may initially present with a paraneoplastic syndrome [1]. These systemic manifestations arise from the production of humoral substances by the tumor itself or by remote tissues in the rest of the body via immune-modulation [2]. Common paraneoplastic syndromes [3] associated with RCC can be divided broadly into endocrine and nonendocrine in nature. The most common manifestation of endocrine effects is that of hypercalcemia, whereas polycythemia, hypertension, Cushing syndrome, and galactorrhea are other effects secondary to the autonomic production of hormones. Nonendocrine effects are rarer and include amyloidosis, neuromyopathy, vasculopathy, and glomerulopathy.

It is uncommon for new-onset cardiac symptoms to be the herald of an underlying RCC, and to our knowledge only one prior case report exists regarding the paraneoplastic effect of RCC on the heart [4]. Patients with RCC may have concomitant heart failure, but this is usually a comorbidity that has been present for years.

The patient was a 48-year-old Chinese woman with a history of thalassemia minor but otherwise well. She first presented to the hospital for a routine health screening at which she had complained of a persistent cough for a few months and reported a reduction in exercise tolerance during this period. On the physical examination, she was found to have a pansystolic murmur radiating to the axilla. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed left ventricular hypertrophy with atrial enlargement. Chest x-ray confirmed an increased cardiothoracic ratio, left atrial enlargement, and blunting of the left costophrenic angle. In view of findings suggestive of heart failure, the patient was referred to a cardiologist for further management.

On further questioning, the patient reported that she had experienced a loss of appetite and loss of weight over the preceding 2 months and was having occasional left-sided abdominal discomfort. In addition to the systolic murmur, the cardiologist found an abdominal mass measuring 10 cm in the left hypochondrium, which he could not get above cranially and which descended with respiration. With an initial working diagnosis of possible infective endocarditis with splenomegaly, a transthoracic echocardiogram and an ultrasound of the abdomen were obtained.

The transthoracic echocardiogram showed a lef t ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 34%. There was moderate global left ventricular hyperkinesia, mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, and a severely dilated left atrium (Fig. 1). No valvular vegetations were seen. The results of an ECG and measurement of cardiac enzyme markers were also unremarkable. A computed tomography (CT) coronary angiogram was ordered for further evaluation, revealing normal coronary arteries and an Agatston calcium score of 0.

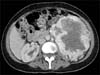

The abdominal ultrasound done after the echocardiogram revealed a large left kidney measuring 14 cm with a large heterogeneous solid mass-like component predominantly in the mid and upper pole with adjacent increased vascularity, suspicious for a renal malignancy. The patient was referred to our urology department for further management. We performed a CT intravenous pyelogram (Figs. 2, 3), which clearly illustrated a large left renal mass measuring 14 cm×13 cm×11 cm and arising from the mid/lower pole with involvement of the renal pelvis, ureter, and left adrenal gland. The staging scans showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient was offered an open left radical nephrectomy.

Intraoperatively, a locally advanced left renal tumor was noted, with involvement of the mesentery of the descending colon. A decision was made to perform en bloc left hemi colectomy along with radical nephrectomy.

Postoperatively, the patient recovered well without any complications. On postoperative day 8, we repeated a transthoracic echocardiogram. Heart function had dramatically improved, with an increased LVEF of 45% to 50%, whereas the global left hyperkinesia was noted to have resolved. The patient was eventually discharged on postoperative day 8.

Final histology revealed a clear cell RCC with predominant sarcomatoid features, involving at least 90% of the lesion. The tumor measured 14 cm and was noted to have invaded into the perinephric tissues, beyond Gerota's fascia, and into the adrenal gland. The tumor was of Fuhrman's nuclear grade 4 and vascular invasion was seen but the resection margins were free of tumor. A regional lymph node was negative for metastasis, whereas 1 of 3 nodules invading into the descending colon was positive for disease.

Heart failure results from either systolic or diastolic dysfunction. It can be secondary to many causes-either structural or functional-and can be broadly classified into ischemic and nonischemic causes. Ischemic cardiomyopathy was ruled out in our patient after a CT coronary angiogram was performed, which revealed normal coronary arteries.

Nonischemic heart failure is usually idiopathic in nature, but this is a diagnosis of exclusion after other causes have been ruled out [5]. Structural etiologies include cardiomyopathy secondary to viral myocarditis, alcohol and substance abuse, chemotherapy agents, and infiltrative diseases. Hypertensive heart disease and valvular dysfunction secondary to connective tissue disorders are other possible causes.

Functional causes of heart failure are usually 'high output' in nature, characterized by an elevated cardiac index. However, most of these causes are rarely the sole cause of heart failure and are merely triggers to an underlying pathology [6]. Causes include anemia, vitamin deficiencies such as beriberi or thiamine deficiency, hyperthyroidism, renal disease, and systemic arteriovenous fistulas or malformations.

Our patient had anemia with a baseline hemoglobin concentration of about 9 to 10 g/dL. However, this alone is unlikely to cause significant heart failure as demonstrated by Brannon et al. [7], who showed that patients develop heart failure only in severe cases of anemia with hemoglobin levels of less than 5 g/dL. Even though our patient had a large left-sided RCC, her right kidney was functioning normally and her creatinine clearance test was normal, hence ruling out renal impairment as a cause of heart failure.

Yet another cause of functional heart failure is that of stress-induced cardiomyopathy, also known as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or broken heart syndrome [8]. Various studies have reported the incidence of cardiomyopathy triggered by intense emotional stress following an acute event in a person's life such as that of a catastrophic medical diagnosis [9]. This phenomenon is more commonly seen in postmenopausal women, presenting with symptoms mimicking that of an acute myocardial infarction, coupled with ECG abnormalities and elevated cardiac enzymes. Most patients typically recover within a month, with reversal in biochemical and perfusion abnormalities [10]. It is possible that our patient had developed Takotsubo cardiomyopathy; however, apart from the depressed LVEF shown on the echocardiogram, she did not have any abnormalities in her ECG or cardiac markers. Furthermore, the temporal sequence of events was such that the RCC was picked up incidentally on the ultrasound that was performed after her echocardiogram, and she had no prior knowledge that she may have an underlying malignancy.

Although all of the above-stated causes are possible etiologies of heart failure in the present case, it is not inconceivable that RCC played a direct causative role via paraneoplastic systemic effects. Vieira et al. [4] reported a case of stress cardiomyopathy in which an elderly woman presented with acute chest pain but a coronary angiogram did not reveal any abnormalities. Subsequently, a magnetic resonance scan of the heart picked up an occult right renal tumor. The authors postulated that the RCC had triggered transient catecholamine-mediated myocardial apical stunning, resulting in symptoms mimicking that of an acute coronary event.

A feature of paraneoplastic syndromes lies in the resolution of symptoms or biochemical abnormalities af ter treatment of the primary malignancy. In our patient, resection of the tumor resulted in a significant improvement in the extent of her cardiomyopathy, proving that acute heart failure was secondary to systemic effects of the tumor on the heart, resulting in a form of stress cardiomyopathy. However, much research has to be done to support this hypothesis, because no known hormones or chemical mediators have been implicated in the causation of heart failure, apart from catecholamines, which may cause an increase in sympathetic drive on the heart.

Looking at things from another perspective, a patient with a resectable renal tumor should not be deprived of a chance to undergo surgery, just because his or her 'ejection fraction is too low' to undergo general anaesthesia. Surgery may in fact be the only chance to provide a cure for such patients.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Wall motion diagram of first transthoracic echocardiogram. AA, apical anterior; AI, apical inferior; AL, apical lateral; AS, apical septal; BA, basal anterior; BAL, basal anterior lateral; BAS, basal anterior septal; BI, basal inferior; BIL, basal inferior lateral; BIS, basal inferior septal; MA, mid anterior; MAL, mid anterior lateral; MAS, mid anterior septal; MI, mid inferior; MIL, mid inferior lateral; MIS, mid inferior septal.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the medical and nursing staff who were involved in the care of the patient during her stay.

References

1. Gold PJ, Fefer A, Thompson JA. Paraneoplastic manifestations of renal cell carcinoma. Semin Urol Oncol. 1996; 14:216–222.

2. John WJ, Foon KA, Patchell RA. Paraneoplastic syndromes. In : DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven;1997. p. 2397–2422.

3. Palapattu GS, Kristo B, Rajfer J. Paraneoplastic syndromes in urologic malignancy: the many faces of renal cell carcinoma. Rev Urol. 2002. 4:p. 163–170.

4. Vieira MS, Antunes N, Carvalho H, Torres S. Renal cell carcinoma presenting as a stress cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013; 14:192.

5. Felker GM, Thompson RE, Hare JM, Hruban RH, Clemetson DE, Howard DL, et al. Underlying causes and long-term survival in patients with initially unexplained cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342:1077–1084.

6. Mehta PA, Dubrey SW. High output heart failure. QJM. 2009; 102:235–241.

7. Brannon ES, Merrill AJ, Warren JV, Stead EA. The cardiac output in patients with chronic anemia as measured by the technique of right atrial catheterization. J Clin Invest. 1945; 24:332–336.

8. Akashi YJ, Goldstein DS, Barbaro G, Ueyama T. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new form of acute, reversible heart failure. Circulation. 2008; 118:2754–2762.

9. Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, Baughman KL, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:539–548.

10. Abe Y, Kondo M, Matsuoka R, Araki M, Dohyama K, Tanio H. Assessment of clinical features in transient left ventricular apical ballooning. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 41:737–742.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download