Abstract

Hydatid disease is endemic in parts of India, yet genitourinary involvement is rare. Laparoscopic management of such cases is uncommonly reported. We present a case of an adrenal hydatid and its management by laparoscopic aspiration, instillation of scolicidal solution, and partial excision of the cyst.

Hydatid disease is a parasitic infestation caused by Echinococcus granulosus that is endemic in India, Australia, New Zealand, Africa, Southern Europe, and South America [1]. Genitourinary involvement is extremely rare and constitutes less than 5% of all cases. The liver is the most frequent organ involved (45% to 75% of cases), followed by the lungs (10% to 50% of cases). Heart, spleen, kidney, and brain are less commonly involved and represent about 10% of cases [2]. Hydatid cyst of the adrenal gland (HCAG) constitutes less than 1% of cases [3,4]. Humans become infected with E. granulosus by consuming contaminated food or by direct contact with infected animals. Small and uncomplicated cysts are usually asymptomatic, but about 80% of patients have symptoms. In endemic areas, an equal sex distribution is noted [1].

A 51-year-old woman presented with left upper abdominal pain that had persisted for the past 6 months. The results of a physical examination were unremarkable. The results of a complete blood cell count, electrolyte count, eosinophil count, serum biochemistry, and urinalysis were within normal limits. The chest x-ray was normal and ultrasound examination revealed a heterogeneous cystic mass between the upper pole of the left kidney and the spleen. Computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated the presence of a solitary cystic mass within the left adrenal gland with no enhancement suggestive of adrenal echinococcosis. No other intra-abdominal or intrathoracic masses were found (Fig. 1). Urinary catecholamines and metanephrine levels were within normal limits. The serology for E. granulosus was positive. On further enquiry, the patient confirmed a history of animal contact. On the basis of these findings, the patient was started on albendazole for 4 weeks and a plan for surgical excision was formulated.

The diagnosis was confirmed during the surgery. The cyst was approached laparoscopically by the transperitoneal route. The rest of the peritoneal cavity did not reveal any other lesions. The area around the cyst was carefully packed with gauzes soaked in betadine solution. The cyst was aspirated during the procedure and 10% betadine solution was filled inside the cyst and maintained for 10 minutes. An appropriate dissection plane between the cyst and the adrenal gland could not be found. Hence, a 10-mm trocar was introduced inside the cyst and the cyst contents were sucked out, including the germinal layer (Fig. 2). Partial excision of the cyst wall was done because the cyst was adherent to the renal vessels. Pathological examination of the specimen confirmed the diagnosis. The wall of the adrenal gland showed cells in clusters and also singly with necrosis in the background. The hooklet of the parasite was also demonstrated as an acid-fast structure on the pathology slide (Fig. 3). The patient's postoperative course was uneventful. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient was free of recurrence.

Adrenal cysts are rare, with an incidence at autopsy of 0.06% to 0.18% [5]. HCAG is exceptional and accounts for only 6% to 7% of all adrenal cysts [1,5], but in endemic areas, most of the adrenal cysts requiring surgical interventions are of a hydatid nature. In a series of 15 patients with adrenal cysts, published by Akcay et al. [3], 9 were hydatid cysts. The classification of adrenal cysts as described by Foster [5] includes (1) true cysts, which are endothelial cysts, mainly hemangiomas and lymphangiomas (45%), and epithelial cysts like glandular retention cysts and embryonic cysts (9%); and (2) pseudocysts caused by hemorrhage (39%) [5]. Most of the time, adrenal cysts are asymptomatic and are diagnosed at autopsy [5] or incidentally [3]. However, patients may present with vague and nonspecific symptoms. The most prominent clinical features consist of dull pain in the flanks [3]. As reported, HCAG causes hypertension, known as Goldblatt phenomenon, which is explained by irritation of the functional tissue of the adrenal gland by the growing cyst [6]. Hypertension is usually curable by cyst ablation. Anaphylactic shock can result from the rupture of a hydatid cyst and is considered a serious complication [7]. Serology is useful in the diagnosis of hydatid disease. However, the sensitivity of serology tests is determined by the site and condition of hydatid cysts in the body [8]. Hydatid cysts in human lungs, spleen, or kidneys tend to be associated with lower serum antibody levels than found with cysts in the liver [8]. Many authors think that parasitic involvement of the adrenals is usually secondary and part of a generalized echinococcosis [3,7]. Tiny curvilinear calcifications in the suprarenal area seen on plain radiography are suggestive of a hydatid cyst [9], although tuberculous or hemorrhagic pseudocysts may calcify [9]. On a CT scan, a smooth, round, low-density, noncontrast-enhanced mass with a thin wall is very suggestive. CT scans can also show peripheral linear or punctuate calcifications or peripheral small fluid collections from secondary vesicles (daughter cyst sign) [9]. The sensitivity of a CT scan in abdominal echinococcosis is estimated to be 97%. Magnetic resonance imaging is not cost-effective in the diagnosis of hydatid disease. CT-guided needle aspiration is not indicated when a hydatid cyst is suspected because of the high risk of dissemination and anaphylactic shock. Treatment of HCAG is mainly surgical and by total cyst excision; however, when the cyst is large and adherent to adjacent structures that need to be preserved, partial pericystectomy and adequate drainage of the remaining cystic cavity is an acceptable alternative. Total adrenalectomy is not mandatory and is performed when the cyst has completely destroyed the gland. The surgical approach through a laparotomy has the advantage of allowing exploration of the peritoneal cavity. Laparoscopic resection of an adrenal hydatid cyst can also be an adequate procedure [4] and there are reports of successful management of a genitourinary hydatid cyst by laparoscopy. It is of utmost importance to inactivate the cyst before manipulation. Prior to dissection, a scolicidal agent is injected inside the cyst to destroy daughter cysts and scolices and to avoid spillage of viable cystic content resulting in secondary echinococcosis. Chemotherapy with albendazole and mebendazole is of questionable value and should be reserved for inoperable patients and those with disseminated lesions [10].

In conclusion, HCAG is an exceptional location that should be kept in mind in endemic areas or in patients with a history of hydatid disease. Diagnosis is based mainly on ultrasound and CT. Partial excision of the cyst with preservation of the adrenal gland is the treatment of choice. Total excision of an adrenal hydatid when adherent to the renal hilum can lead to disaster.

Figures and Tables

FIG. 1

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showing a cystic lesion involving the left adrenal gland.

FIG. 2

(A, B) Intraoperative photograph showing cyst aspiration by directly inserting a trocar into the cyst and laparoscopic cyst dissection after aspiration.

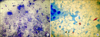

FIG. 3

(A) Histopathology image showing adrenal cortical cells in clusters as well as scattered singly with necrosis in the background (MGG stain, ×400). (B) One of the hooklets of the hydatid cyst seen along with a multinucleated giant cell. The hooklet was seen as an acid-fast structure in Ziehl-Neelsen stain (×1,000).

References

1. Goel MC, Agarwal MR, Misra A. Percutaneous drainage of renal hydatid cyst: early results and follow-up. Br J Urol. 1995; 75:724–728.

2. Kern P, Bardonnet K, Renner E, Auer H, Pawlowski Z, Ammann RW, et al. European echinococcosis registry: human alveolar echinococcosis, Europe, 1982-2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003; 9:343–349.

3. Akcay MN, Akcay G, Balik AA, Boyuk A. Hydatid cysts of the adrenal gland: review of nine patients. World J Surg. 2004; 28:97–99.

4. Defechereux T, Sauvant J, Gramatica L, Puccini M, De Micco C, Henry JF. Laparoscopic resection of an adrenal hydatid cyst. Eur J Surg. 2000; 166:900–902.

5. Foster DG. Adrenal cysts: review of literature and report of case. Arch Surg. 1966; 92:131–143.

6. Yeniyol CO, Minareci S, Ayder AR. Primary cyst hydatid of adrenal: a case report. Int Urol Nephrol. 2000; 32:227–229.

7. Schoretsanitis G, de Bree E, Melissas J, Tsiftsis D. Primary hydatid cyst of the adrenal gland. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1998; 32:51–53.

8. Craig PS. Immunodiagnosis of echinococcosis granulosus and comparison of techniques for diagnosis of canine echinococcosis. In : Andersen FL, Ouhelli H, Kachani M, editors. Compendium on cystic Echinococcosis in Africa and Middle Eastern countries with special reference to Morocco. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University;1997. p. 85–118.

9. Horchani A, Nouira Y, Chtourou M, Kacem M, Ben Safta Z. Retrovesical hydatid disease: a clinical study of 27 cases. Eur Urol. 2001; 40:655–660.

10. Saimot AG. Medical treatment of liver hydatidosis. World J Surg. 2001; 25:15–20.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download