Abstract

Purpose

To elucidate the impact of surgical varicocele repair on the pregnancy rate through new meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials that compared surgical varicocele repair and observation.

Materials and Methods

The PubMed and Embase online databases were searched for studies released before December 2012. References were manually reviewed, and two researchers independently extracted the data. To assess the quality of the studies, the Cochrane risk of bias as a quality assessment tool for randomized controlled trials was applied.

Results

Seven randomized clinical trials were included in our meta-analyses, all of which compared pregnancy outcomes between surgical varicocele repair and control. There were differences in enrollment criteria among the studies. Four studies included patients with clinical varicocele, but three studies enrolled patients with subclinical varicocele. Meanwhile, four trials enrolled patients with impaired semen quality only, but the other three trials did not. In a meta-analysis of all seven trials, a forest plot using the random-effects model showed an odds ratio (OR) of 1.90 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77 to 4.66; p=0.1621). However, for subanalysis of three studies that included patients with clinical varicocele and abnormal semen parameters, the fixed-effects pooled OR was significant (OR, 4.15; 95% CI, 2.31 to 7.45; p<0.001), favoring varicocelectomy.

The most common cause of male infertility is varicocele, which can be detected in at least 35% of infertile men and is generally correctable or at least treatable [1,2]. Varicocele repair includes a variety of surgical options, including retroperitoneal, inguinal, subinguinal, and scrotal approaches, and percutaneous techniques such as embolization and sclerotherapy [3-5]. Subsequent pregnancy rates are estimated to be 38.4% after varicocele repair by pooled analysis [6]. However, the role of varicocele repair for the treatment of subfertile men has been questioned during the past decades [7]. Although varicocele repair can induce improvements in semen quality, the obvious benefit of spontaneous pregnancy has not been shown in several meta-analyses.

A Cochrane Collaboration conducted meta-analyses for assessing the effects of varicocele repair on pregnancy since 2001 [8]. They showed consistently that there is no beneficial effect of varicocele treatment on a couple's chance of conception [9]. A more recent meta-analysis published in 2012 suggested that varicocele repair in men from couples with otherwise unexplained subfertility may improve pregnancy outcome, although this finding is inconclusive owing to the low quality of the available data [10]. The aforementioned meta-analyses included data from surgical repair and percutaneous embolization. Although these procedures have been performed to prevent venous reflux into the scrotum, there exists a fundamental difference in that the veins are neither ligated nor divided during percutaneous embolization, which is unlikely to lead to a surgical repair [11]. There remain critical concerns that recurrence rates after percutaneous embolization might be much higher than the reported data, likely as the result of recannulization through the coils. For this reason, the outcomes of both surgical and percutaneous varicocele repairs need to be evaluated separately. Herein, we introduce new meta-analyses to elucidate the role of surgical varicocele repair in the treatment of male subfertility.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that met the following criteria were included: 1) a study design that included comparison of pregnancy outcomes between treated and control groups after surgical varicocele repair in men from couples with otherwise unexplained subfertility; 2) a study that provided accurate postoperative recovery data for fertility that could be analyzed, including the total number of subjects and the values of each index; and 3) the full text of the study or abstract presented at a scientific congress could be accessed.

A literature search was carried out for all publications prior to 31 December 2012 in the PubMed and Embase online databases. A cross-reference search of eligible articles was carried out to identify additional studies not found by the computerized search. The following keywords were used to search the databases: varicocele, fertility, repair, and surgery. Studies were limited to humans.

One researcher (K.H.K.) screened the titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy. The other two researchers (J.Y.L. and D.H.K.) independently assessed the full text of the papers to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. The databases were designed to ensure the most relevant data with respect to author, year of publication, patient demographics, treatments, fertility rates, and inclusion of a reference standard. Disagreements were resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached or by arbitration employing another researcher (K.S.C.).

Once the final group of articles was agreed upon, two researchers (J.Y.L. and D.H.K.) independently examined the quality of each article by using the Cochrane risk of bias as a quality assessment tool for RCTs. Quality assessment was carried out by using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5.2.3, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

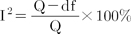

Heterogeneity among studies was explored by using the Q statistic and Higgins' I2 statistic [12]. Higgins' I2 measures the percentage of total variation due to heterogeneity rather than chance across the studies. Higgins' I2 is calculated as follows:

where Q is Cochran heterogeneity statistic and df is the degrees of freedom.

An I2 greater than 50% is considered to represent substantial heterogeneity. For the Q statistic, heterogeneity was deemed to be significant for p less than 0.10 [13]. When there was evidence of heterogeneity, the data were analyzed by using a random-effects model to obtain a summary estimate for the test sensitivity with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Analyses of studies in which positive results were confirmed were conducted by using a pooled specificity with 95% CIs.

When a significant Q test indicated heterogeneity across studies (p<0.10 or I2>50%), the random-effects model was used for the meta-analysis; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used [14]. The Begg and Mazumdar [15] rank-correlation test and Egger et al. [16]'s regression intercept test were used to provide evidence of publication bias, which was shown as a funnel plot (p<0.05 was considered a significant publication bias). The meta-analysis of comparable data was carried out by using R (R ver. 2.15.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.r-project.org).

The database search found 28 articles that could potentially be included in the meta-analysis. On the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 19 articles were excluded after a simple reading of the titles and abstracts, and 2 articles were excluded because of the patient population. In total, seven articles were included in the analysis for surgical varicocele repair versus control (Table 1) [17-23]. There were differences in enrollment criteria among these studies. Four studies included patients with clinical varicocele, but three studies enrolled patients with subclinical varicocele. Meanwhile, four trials enrolled patients with impaired semen quality only, but the other three trials did not. Of these, three articles were included in the subanalysis for surgical varicocele repair versus control in patients with clinical varicocele and impaired semen quality (Fig. 1). The results of the methodological quality of included RCTs on each item of bias risk based on the Cochrane handbook are listed in Fig. 2.

Forest plots are shown in Fig. 3. A heterogeneity test showed the following: chi-square=16.8 with 6 df (p=0.010) and I2=64.1% in the analysis for all seven studies; chi-square=2.51 with 2 df (p=0.285) and I2=20.4% in the subanalysis for the three studies that included the patients with clinical varicocele and impaired semen quality. Notable heterogeneities were detected in the analysis for all studies; thus, random-effects models were used to further assess these variables. However, there was no significant heterogeneity in the subanalysis, so fixed effect models were applied. In radial plots, no variables demonstrated heterogeneity after selection of effect models for each variable (Fig. 4).

The Begg and Mazumdar rank-correlation test showed no evidence of publication bias in the present meta-analysis (all 7 studies, p=1.000; 3 studies with clinical varicocele and impaired semen quality, p=0.333). Egger regression intercept test also revealed no evidence of publication bias in any meta-analysis (all 7 studies, p=0.607; 3 studies with clinical varicocele and impaired semen quality, p=0.114). Funnel plots from these three meta-analyses are shown in Fig. 5.

In a meta-analysis of surgical varicocele repair versus control from all seven studies, the forest plot using the random-effects model showed an odds ratio (OR) of 1.90 (95% CI, 0.77 to 4.66) favoring varicocelectomy, but there were no significant differences in the two groups (p=0.1621) (Fig. 3A). For the subanalysis of patients with clinical varicocele and impaired semen quality, the fixed-effects pooled OR was significant (OR, 4.15; 95% CI, 2.31 to 7.45; p<0.001) (Fig. 3B), favoring varicocelectomy.

In the present meta-analysis, we included only RCTs and assessed the effects of surgical varicocele repair on spontaneous pregnancy rates; the OR (4.16) favored surgical varicocele repair when it was performed in men with clinical varicocele and abnormal semen parameters. In 2007, Marmar et al. [24] reported the first meta-analysis for evaluating the value of surgical varicocelectomy as a treatment for male subfertility, at least partly in response to the Cochrane review. Earlier meta-analyses by the Cochrane collaboration simply concluded that there is no evidence that treatment of varicocele in men from couples with otherwise unexplained subfertility improves the couple's chance of conception [25]. However, this finding has been criticized by several investigators, because some RCTs included men with subclinical varicoceles or normal semen analyses, and others had significant dropout rates after randomization [24,26]. For these reasons, Marmar et al. [24] performed another meta-analysis that included five studies (two randomized, three observational) reporting pregnancy rates after varicocelectomy among only men with palpable lesions and at least one abnormal semen parameter. They concluded that varicocelectomy has beneficial effects on fertility status with an OR of 2.87. However, they included three observational studies as well as two RCTs, which could be a weakness of their analysis.

Recently, Baazeem et al. [27] reported a new meta-analysis. Included were 380 couples (192 randomized to treatment and 188 randomized to observation) from four RCTs that reported pregnancy outcomes after repair of clinical varicocele in oligospermic men. The OR resulting from a fixed-effects model was in favor of therapy (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.31 to 3.38; p=0.002). However, the Q-statistic p-value was 0.024, indicating the heterogeneity of their studies (chi-square=14.60 with 3 df). Therefore, they performed the random-effects model owing to severe heterogeneity, and the OR using this model indicated that the differences in the effects of varicocelectomy compared with observation were not statistically significant (OR, 2.23; 95% CI, 0.86 to 5.78; p=0.091). The latest meta-analysis conducted by the Cochrane collaboration suggested that treatment of varicocele in men from couples with otherwise unexplained subfertility may improve a couple's chance of pregnancy, but the authors maintained that the findings were inconclusive, because the quality of the available evidence was very low [6]. In their study, the combined fixed-effects OR for pregnancy rate was 2.39 (95% CI, 1.56 to 3.66), favoring the intervention; however, severe heterogeneity was detected (chi-square=10.97 with 4 df; p=0.03; I2=64%).

On the basis of these recent meta-analyses, the current European Urological Association guidelines on male infertility, which were released in 2012 and 2013, indicate that varicocele repair should be considered in cases of clinical varicocele, oligospermia, infertility duration of more than 2 years, and otherwise unexplained infertility in a couple. This is certainly a meaningful change, considering that the former guidelines indicated that varicocele treatment for infertility should not be undertaken, unless there has been full discussion with the infertile couple regarding the uncertainties of treatment benefit. Besides the meta-analysis, several well-designed studies reported positive effects of treatment on fertility in patients with varicocele. Diegidio et al. [6] reviewed 33 studies and calculated the overall pregnancy rate to be 38.37% (954/2486) by using simple addition and division. In the review, they compared cost-effectiveness and concluded that varicocelectomy is a cost-effective treatment modality for infertility. A subgroup analysis showed that pregnancy rates were highest after the microsurgical subinguinal technique was used. Recently, Abdel-Meguid et al. [23] reported an RCT with a nearly ideal study design that provided a high level of evidence for the effectiveness of varicocelectomy compared with observation. In that study, 150 patients who experienced infertility for more than 1 year and had palpable varicoceles and at least one impaired semen parameter were randomized to a treatment (n=75) or observation (n=75) and were followed for spontaneous pregnancy. Only five patients dropped out during the 12 months after surgery. The results showed a significantly higher pregnancy rate in the treatment arm (32.9% in varicocelectomy vs. 13.9% in observation; OR, 3.0.4; 95% CI, 1.33 to 6.95).

Meanwhile, there are insufficient data to suggest that percutaneous embolization improves a couple's chance of conception. The published meta-analysis showed that the overall spontaneous pregnancy rate of microsurgical varicocelectomy was higher than that of radiographic embolization [28]. The overall failure rate of radiographic embolization was 12.7%, which is much higher than that of microsurgical operation. Some researchers have investigated the treatment effect of surgical varicocele repair versus percutaneous embolization through prospective randomized trials, and their results demonstrated that both treatment modalities seemed to be equivalent in terms of the pregnancy rate [29,30]. Nevertheless, there is an important drawback of percutaneous embolization in the management of subfertile patients with varicocele in the era of evidence-based medicine. To the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence through a RCT that percutaneous embolization for varicocele can improve the pregnancy rate.

The role of surgical repair needs to be reassessed for the aforementioned reasons, and this is the first meta-analysis to be undertaken of only RCTs. Although we suggest that varicocelectomy seems to offer significant advantages in terms of the pregnancy rate, several limitations in our analyses should be considered. To date, high-quality data from well-designed clinical trials are limited; thus, the numbers of RCTs and patients enrolled in our analyses were relatively small. In addition, different surgical approaches were applied in each RCT, so there were significant limitations owing to methodological heterogeneity. Accordingly, there is a need for large, properly conducted RCTs of varicocele treatment in men with abnormal semen from couples with otherwise unexplained subfertility. Hopefully, upcoming RCTs will be designed for the evaluation of spontaneous pregnancy after microsurgical varicocelectomy, which is regarded as the gold standard.

Our new meta-analysis suggests that surgical varicocele repair can play a significant role in improving the pregnancy rate when performed in men with clinical varicocele and abnormal semen parameters from couples with otherwise unexplained subfertility. Therefore, surgical repair should be offered as the first-line treatment for clinical varicocele in subfertile men.

Figures and Tables

FIG. 2

Methodological quality graph. Two researchers' judgments about each methodological quality item are presented as percentages across all included studies.

FIG. 3

Forest plots. (A) Overall meta-analysis of surgical varicocele repair versus control. (B) Subanalysis for 3 studies that included men with clinical varicocele and impaired semen quality. Squares represent study-specific risk estimates (size of square reflects the study statistical weight); horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals (CIs); diamonds represent summary relative risk estimate with its corresponding 95% CI. OR, odds ratio.

FIG. 4

Radial plots of variables with regard to heterogeneity after selection of effect models for all seven studies (A) and three studies (B) that included men with clinical varicocele and impaired semen quality.

References

1. Kass EJ, Reitelman C. Adolescent varicocele. Urol Clin North Am. 1995; 22:151–159.

2. Schlesinger MH, Wilets IF, Nagler HM. Treatment outcome after varicocelectomy: a critical analysis. Urol Clin North Am. 1994; 21:517–529.

3. Choi WS, Kim SW. Current issues in varicocele management: a review. World J Mens Health. 2013; 31:12–20.

4. Kang DH, Lee JY, Chung JH, Jo JK, Lee SH, Ham WS, et al. Laparoendoscopic single site varicocele ligation: comparison of testicular artery and lymphatic preservation versus complete testicular vessel ligation. J Urol. 2013; 189:243–249.

5. Seo JT, Kim KT, Moon MH, Kim WT. The significance of microsurgical varicocelectomy in the treatment of subclinical varicocele. Fertil Steril. 2010; 93:1907–1910.

6. Diegidio P, Jhaveri JK, Ghannam S, Pinkhasov R, Shabsigh R, Fisch H. Review of current varicocelectomy techniques and their outcomes. BJU Int. 2011; 108:1157–1172.

7. Lee HS, Seo JT. Advances in surgical treatment of male infertility. World J Mens Health. 2012; 30:108–113.

8. Evers JL, Collins JA, Vandekerckhove P. Surgery or embolisation for varicocele in subfertile men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001; CD000479.

9. Evers JH, Collins J, Clarke J. Surgery or embolisation for varicoceles in subfertile men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; CD000479.

10. Kroese AC, de Lange NM, Collins J, Evers JL. Surgery or embolization for varicoceles in subfertile men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; 10:CD000479.

11. Goldstein M. Surgical management of male infertility. In : Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh urology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;2012. p. 678–687.

12. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003; 327:557–560.

13. Fleiss JL. Analysis of data from multiclinic trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986; 7:267–275.

14. DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: an update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007; 28:105–114.

15. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994; 50:1088–1101.

16. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997; 315:629–634.

17. Yamamoto M, Hibi H, Hirata Y, Miyake K, Ishigaki T. Effect of varicocelectomy on sperm parameters and pregnancy rate in patients with subclinical varicocele: a randomized prospective controlled study. J Urol. 1996; 155:1636–1638.

18. Unal D, Yeni E, Verit A, Karatas OF. Clomiphene citrate versus varicocelectomy in treatment of subclinical varicocele: a prospective randomized study. Int J Urol. 2001; 8:227–230.

19. Nilsson S, Edvinsson A, Nilsson B. Improvement of semen and pregnancy rate after ligation and division of the internal spermatic vein: fact or fiction? Br J Urol. 1979; 51:591–596.

20. Madgar I, Weissenberg R, Lunenfeld B, Karasik A, Goldwasser B. Controlled trial of high spermatic vein ligation for varicocele in infertile men. Fertil Steril. 1995; 63:120–124.

21. Grasso M, Lania C, Castelli M, Galli L, Franzoso F, Rigatti P. Low-grade left varicocele in patients over 30 years old:the effect of spermatic vein ligation on fertility. BJU Int. 2000; 85:305–307.

22. Dohle GR. Does varicocele repair result in more spontaneous pregnancies? A randomised prospective trial. Int J Androl. 2010; 33:29.

23. Abdel-Meguid TA, Al-Sayyad A, Tayib A, Farsi HM. Does varicocele repair improve male infertility? An evidence-based perspective from a randomized, controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2011; 59:455–461.

24. Marmar JL, Agarwal A, Prabakaran S, Agarwal R, Short RA, Benoff S, et al. Reassessing the value of varicocelectomy as a treatment for male subfertility with a new meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2007; 88:639–648.

25. Evers JL, Collins JA. Surgery or embolisation for varicocele in subfertile men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004; CD000479.

26. Ficarra V, Cerruto MA, Liguori G, Mazzoni G, Minucci S, Tracia A, et al. Treatment of varicocele in subfertile men: the Cochrane review: a contrary opinion. Eur Urol. 2006; 49:258–263.

27. Baazeem A, Belzile E, Ciampi A, Dohle G, Jarvi K, Salonia A, et al. Varicocele and male factor infertility treatment: a new meta-analysis and review of the role of varicocele repair. Eur Urol. 2011; 60:796–808.

28. Cayan S, Shavakhabov S, Kadioglu A. Treatment of palpable varicocele in infertile men: a meta-analysis to define the best technique. J Androl. 2009; 30:33–40.

29. Sayfan J, Soffer Y, Orda R. Varicocele treatment: prospective randomized trial of 3 methods. J Urol. 1992; 148:1447–1449.

30. Nieschlag E, Behre HM, Schlingheider A, Nashan D, Pohl J, Fischedick AR. Surgical ligation vs. angiographic embolization of the vena spermatica: a prospective randomized study for the treatment of varicocele-related infertility. Andrologia. 1993; 25:233–237.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download