Abstract

Purpose

To present clinical and histological features of prepubertal testicular tumors through the analysis of the long-term experiences of a single surgeon.

Materials and Methods

The charts of 48 children treated for testicular tumors from 1986 to 2010 were retrospectively reviewed. All patients underwent radical orchiectomy. The patients' ages, clinical presentations, histopathological findings, kinetics of tumor markers, and outcomes were recorded.

Results

The patients' median age at the initial diagnosis was 19.5 months (range, 3 to 84 months). All patients presented with either a palpable mass (76%) or scrotal size discrepancy (24%). Compared with a palpable mass, scrotal size discrepancy led to delay in diagnosis by 5 months. Regarding histology, yolk sac tumors and teratomas accounted for 53% and 36% of the tumors, respectively. The mean preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level was significantly higher in patients with yolk sac tumors than in those with teratomas (4,600 ng/mL vs. 6.3 ng/mL), and only one patient with a teratoma had a preoperative AFP value higher than 20 ng/mL. Following radical orchiectomy, 72%, 8%, and 16% of patients with a yolk sac tumor showed normalization, persistent elevation, and relapse after transient lowering of AFP, respectively. Preoperative AFP was greater in patients with non-normalization than in those with normalization. Five of six patients with non-normalization showed evidence of either vascular invasion or endolymphatic tumor emboli.

Prepubertal testicular tumors (PTTs) are rare, representing 1% to 2% of all pediatric solid tumors and with an annual incidence of 0.5 to 2 per 100,000 children [1]. Most information regarding PTTs is based on experience with the adult counterpart; however, recently published data indicate that PTTs are distinct from postpubertal tumors with regard to histological distribution, clinical course, and management algorithm [2-5]. For instance, whereas seminoma or mixed histology is dominant in adult testicular tumors, PTTs are mainly composed of teratomas or yolk sac tumors [2].

The distribution of histological types of PTTs remains controversial. Whereas yolk sac tumors are known as the most common PTTs [2], a growing number of recent studies have indicated that teratomas are more frequent than yolk sac tumors [3,4]. Some have speculated that this disparity in racial differences is based on genetic or environmental discrepancies, whereas others believe that it was just reporting bias [6-8]. Because the recent data on PTTs showing the predominance of teratomas reflect the case of Western countries, the explanation of racial differences seems plausible and should be verified. Unfortunately, only limited Asian data are available, thus making direct comparison difficult [9-11].

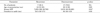

Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) has been widely used to evaluate patients with PTTs. Its elevation usually reflects the presence of components of yolk sac tumors, but it is neither sensitive nor specific to yolk sac tumors (Fig. 1). For example, the elevation of AFP is well known in benign teratomas and even in normal infants. This may create a problem when considering testis-sparing surgery for a benign teratoma. Because there are no reliable United States criteria for diagnosing benign versus malignant testis lesions, an understanding of the possible range of AFP in a specific tumor that may differentiate a benign teratoma from a yolk sac tumor would be beneficial in preoperative planning.

Also, serum AFP is believed to be useful in monitoring treated patients with yolk sac tumors. However, owing to the small number of patients, few data are available regarding the fate of patients who fail to achieve or maintain normalization.

To address the aforementioned issue, we analyzed our experience of 22 years. We believe that this kind of single-institutional study has an advantage in that all pathology and clinical data can be tracked and analyzed in a similar fashion, thus minimizing reporting bias.

Following approval of the Institutional Review Board, we obtained the medical records of 52 prepubertal patients aged less than 12 years who were treated for testicular tumors at Seoul National University Children's Hospital (SNUCH) from 1986 to 2010. Among these patients, the records of 48 patients had complete pathologic and follow-up data and thus were eligible for review. Parameters such as age at operation (month), initial presentation, duration of time from initial presentation to diagnosis, pre operative and postoperative AFP, beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), evaluations of preoperative metastatic lesions, clinical stage, histological type, adjuvant therapy and its response, and follow-up periods were studied. The diagnosis and treatment algorithm in SNUCH was as follows: patients suspected of having a testicular tumor were assessed by measurement of tumor markers (AFP, β-hCG) and scrotal ultrasonography with plain X-rays. In case of suspicious malignancy, abdomen computed tomography was obtained to evaluate the retroperitoneal lymph node or distant metastasis. Then, all patients underwent radical inguinal orchiectomy and pathologic results were obtained. Further management was determined in accordance with tumor histology and stage. All patients with stage 1 yolk sac tumors were followed with regular measurement of serum AFP levels.

The SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. All clinical parameters were analyzed by the chi-square, Mann-Whitney U test and are reported as median values with ranges. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

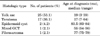

The clinical data of the 48 patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 19.5 months (range, 3 to 84 months). Three-quarters of patients presented owing to a palpable mass and the remaining cases were detected by size discrepancy. The former group of patients preceded the latter by 5 months in terms of mean time to diagnosis (2.5 vs. 7.5, p<0.05).

The tumors were right-sided in 21 boys (44%) and left-sided in 27 boys (56%). Preoperative staging indicated that 45 patients (93.8%) had localized tumors without lymph node or distant metastasis. Pathology revealed 25 yolk sac tumors (53%), 17 teratomas (36%), 2 embryonal carcinomas (4.2%), 2 epidermoid cysts (4.2%), 1 mixed germ cell tumor (2.1%), and 1 fibrosarcoma (2.1%) (Table 2). Twenty-three patients (92%) with yolk sac tumors had stage I tumors at the time of diagnosis.

Table 3 shows the comparison of clinical variables between the patients with yolk sac tumors and those with teratomas. Only mean preoperative AFP differed significantly between the two groups. The AFP level of patients with a yolk sac tumor was significantly higher than that of patients with a teratoma. Given that the normal range of AFP is less than 20 ng/mL, all patients with yolk sac tumors showed supranormal values, whereas only one patient in the teratoma group had an AFP value higher than normal. That patient was a 17-month-old boy and his preoperative AFP at the time of diagnosis was 39 ng/mL.

The median follow-up period was 62 months (range, 1 to 192 months). Regarding the AFP responses of yolk sac tumors, 18 patients (72%) had normalized AFP values following radical orchiectomy, 2 patients (8%) showed persistent elevation of AFP, 4 patients (16%) relapsed after normalization of AFP, and 1 patient was lost to follow-up during the period of the present study. The median time to relapse of AFP was 8 months (range, 6 to 12 months). All 6 patients who showed either elevation or relapse of AFP received salvage chemotherapy. This therapy rescued all but 1 patient, who was further treated by peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. No patient experienced relapse after these treatments.

Comparison of mean preoperative AFP between nonrelapsed and relapsed patients revealed that the AFP of relapsed patients was greater than that of nonrelapsed patients (Table 4). Pathologically, five of six relapsed patients showed evidence of either vascular invasion or endolymphatic tumor emboli.

This retrospective analysis was conducted in a single-institutional Korean cohort, which may be useful in reducing reporting bias. Owing to the rare worldwide incidence of PTTs, we believe that our data, despite the small number of patients in our cohort, will be a valuable addition to the current understanding of PTT. In fact, this study is one of the largest, single-institutional studies of PTT ever reported.

Regarding histological distribution, we confirmed that yolk sac tumors were the most prevalent PTTs in Korea. Our results are consistent with those of another multi-institutional Korean study [9]. In that study, the reported rates of yolk sac tumor and teratoma were 48% and 40%, respectively, a distribution similar to ours. Moreover, a predominance of yolk sac tumors was reported in Japanese and Taiwanese studies, which suggests the predominance of yolk sac tumors in Asian populations [10,11]. However, these distributions are in conflict with recently published United States data, which showed a larger number of benign teratomas over yolk sac tumors [3-5]. The reason for the discrepancy in histological distribution remains unclear, but some reports have provided evidence of racial differences as a possible cause. In an analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data, Walsh et al. [7] found a more than twofold greater incidence of yolk sac tumors among Asian/Pacific Islanders than whites, whereas they found no significant difference in the incidence of teratomas among the ethnic groups. They also reported a higher incidence of teratomas than yolk sac tumors in whites and blacks. These differences may explain the discrepancy in histological distribution among different races. Given the fact that Japanese adults have a lower incidence of testis tumors [8], it is unique that Asian boys are more likely to have yolk sac tumors. Future study will explore what may have caused the higher incidence of yolk sac tumors in Asian boys.

Our data also revealed that more than 70% of patients were rescued by radical orchiectomy only. For the remaining patients experiencing relapse or persistence of disease, chemotherapy was effective in all but one patient and there was no need for retroperitoneal node dissection. These results are in contrast with the reported feature of lymphatic spread and higher metastatic potential of yolk sac tumors in adults [12]. Moreover, the sole need for chemotherapy for relapsed patients was distinct from the case in adult patients, who often required surgical management [13].

In adults, the testis tumor is a typical example of a case in which serum tumor markers play a critical role in diagnosis and management. This is similarly applied to the pediatric counterpart, and dozens of papers have indicated that AFP is useful in diagnosing testis tumors, monitoring the treatment response, and detecting recurrence, whereas β-hCG is not [2,3,14-16]. The present study again confirmed these findings.

Regarding diagnosis, our study underscored the importance of preoperative AFP levels in differentiating yolk sac tumors from teratomas. Whereas all patients with yolk sac tumors showed an elevation of AFP above the reference range (up to 20 ng/mL), only one patient with a teratoma had a serum AFP level (39 ng/mL) that exceeded the reference range. Whereas there was some overlap of serum AFP levels between yolk sac tumor and teratoma patients, no case of teratoma showed a value higher than 100 ng/mL, which is consistent with the results from Ross et al. [2]. If we set 100 ng/mL of AFP as the cutoff for differentiating between the two tumors, we would have missed only one case of yolk sac tumor, thus confirming the diagnostic value of AFP. This is in contrast with other studies, which showed some overlap of AFP ranges between the 2 tumors. The reason may be that our teratoma cohort did not include infants aged less than 6 months old, who show physiologic elevation of serum AFP [17]. However, as long as teratoma infrequently affects infants less than 6 months old, the usefulness of AFP in differential diagnosis cannot be denied.

Our results also indicated the usefulness of AFP in monitoring the disease. Following the orchiectomy, six patients who showed persistence or relapse after normalization of AFP received salvage chemotherapy. This rescued five patients with normalization of AFP. These results indicate that measuring AFP only was enough to monitor the fate of the testis tumor. Although we do not yet have any solid evidence that elevation of AFP will lead to gross recurrence of yolk sac tumors in PTT, the normalization of AFP after salvage chemotherapy may imply the presence of recurrence and suggest that appropriate management be provided. The importance of monitoring AFP in adult series cannot be overemphasized [18].

To further investigate what may be related to relapse in these patients, we compared the clinical and pathological characteristics of the relapsed and nonrelapsed groups to determine the factors that predict AFP relapse. Two statistically significant positive findings were noted. One was that mean preoperative AFP was higher in relapsed patients; however, there was considerable overlap between the two groups, precluding the use of preoperative AFP for a predictive purpose. Another finding was the association of aggressive pathologic behaviors with relapsed patients. It has already been noted that vascular and lymphatic invasion are high-risk factors for relapse in pure or mixed embryonal carcinoma of adult testis [19], and one Japanese study showed that relapse of yolk sac tumors was associated with overt invasion of the testicular vein [20]. However, our data were the first to associate the risk of relapse with vascular or lymphatic invasion in PTT. Despite the small number of patients having positive findings, the lack of false-positive results may be important in predicting relapse and be helpful in planning follow-up in these low-risk patients.

Some limitations of this study should be mentioned. Owing to the small number of patients with a specific histology, we did not draw any meaningful conclusion apart from yolk sac tumors and teratomas. In addition, because we saw only the patients with localized yolk sac tumors, we do not know whether the changes in AFP following treatment might be as good in yolk sac tumors of other stages. Owing to the characteristics of our tertiary care center, the enrolled patients may not show the histological distribution seen in other hospitals in Korea. Despite these limitations, we believe that our data will enhance knowledge about this rare tumor.

Our single-center 25 years of experience showed a dominance of yolk sac tumors over teratomas, which is attributable to racial differences that may originate from genetic factors rather than epidemiologic influence. Compared with the adult counterpart, childhood yolk sac tumors demonstrated a more benign course and responded well to chemotherapy, even in relapse. Relapsed yolk sac tumors often showed aggressiveness on pathologic examination, and AFP was found to be the most useful marker in the diagnosis and follow-up of childhood yolk sac tumors.

Figures and Tables

FIG. 1

Comparison of preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) between patients with yolk sac tumors and those with teratomas.

References

1. Brosman SA. Testicular tumors in prepubertal children. Urology. 1979; 13:581–588.

2. Ross JH, Rybicki L, Kay R. Clinical behavior and a contemporary management algorithm for prepubertal testis tumors: a summary of the Prepubertal Testis Tumor Registry. J Urol. 2002; 168(4 Pt 2):1675–1678.

3. Oottamasathien S, Thomas JC, Adams MC, DeMarco RT, Brock JW 3rd, Pope JC 4th. Testicular tumours in children: a single-institutional experience. BJU Int. 2007; 99:1123–1126.

4. Pohl HG, Shukla AR, Metcalf PD, Cilento BG, Retik AB, Bagli DJ, et al. Prepubertal testis tumors: actual prevalence rate of histological types. J Urol. 2004; 172(6 Pt 1):2370–2372.

5. Metcalfe PD, Farivar-Mohseni H, Farhat W, McLorie G, Khoury A, Bagli DJ. Pediatric testicular tumors: contemporary incidence and efficacy of testicular preserving surgery. J Urol. 2003; 170(6 Pt 1):2412–2415.

6. Gleason AM. Racial disparities in testicular cancer: impact on health promotion. J Transcult Nurs. 2006; 17:58–64.

7. Walsh TJ, Davies BJ, Croughan MS, Carroll PR, Turek PJ. Racial differences among boys with testicular germ cell tumors in the United States. J Urol. 2008; 179:1961–1965.

8. Bray F, Ferlay J, Devesa SS, McGlynn KA, Moller H. Interpreting the international trends in testicular seminoma and nonseminoma incidence. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2006; 3:532–543.

9. Lee SD. Korean Society of Pediatric Urology. Epidemiological and clinical behavior of prepubertal testicular tumors in Korea. J Urol. 2004; 172:674–678.

10. Chen YS, Kuo JY, Chin TW, Wei CF, Chen KK, Lin AT, et al. Prepubertal testicular germ cell tumors: 25-year experience in Taipei Veterans General Hospital. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008; 71:357–361.

11. Kanto S, Saito H, Ito A, Satoh M, Saito S, Arai Y. Clinical features of testicular tumors in children. Int J Urol. 2004; 11:890–893.

12. Foster RS, Hermans B, Bihrle R, Donohue JP. Clinical stage I pure yolk sac tumor of the testis in adults has different clinical behavior than juvenile yolk sac tumor. J Urol. 2000; 164:1943–1944.

13. Baniel J, Foster RS, Gonin R, Messemer JE, Donohue JP, Einhorn LH. Late relapse of testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995; 13:1170–1176.

14. Kay R. Prepubertal Testicular Tumor Registry. J Urol. 1993; 150(2 Pt 2):671–674.

15. Agarwal PK, Palmer JS. Testicular and paratesticular neoplasms in prepubertal males. J Urol. 2006; 176:875–881.

16. Treiyer A, Blanc G, Stark E, Haben B, Treiyer E, Steffens J. Prepubertal testicular tumors: frequently overlooked. J Pediatr Urol. 2007; 3:480–483.

17. Wu JT, Book L, Sudar K. Serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) levels in normal infants. Pediatr Res. 1981; 15:50–52.

18. Dieckmann KP, Albers P, Classen J, De Wit M, Pichlmeier U, Rick O, et al. Late relapse of testicular germ cell neoplasms: a descriptive analysis of 122 cases. J Urol. 2005; 173:824–829.

19. Ayala AG, Ro JY. Testicular tumors: clinically relevant histological findings. Semin Urol Oncol. 1998; 16:72–81.

20. Ikeda H, Matsuyama S, Suzuki N, Takahashi A, Kuroiwa M, Nagashima K, et al. Treatment of a stage I testicular yolk sac tumor with vascular invasion. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1995; 37:537–540.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download