Abstract

Purpose

We evaluated the efficacy of alfuzosin for the treatment of ureteral calculi less than 10 mm in diameter after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL).

Materials and Methods

A randomized, single-blind clinical trial was performed prospectively by one physician between June 2010 and August 2011. A total of 84 patients with ureteral calculi 5 to 10 mm in diameter were divided into two groups. Alfuzosin 10 mg (once daily) and loxoprofen sodium 68.1 mg (as needed) were prescribed to group 1 (n=41), and loxoprofen sodium 68.1 mg (as needed) only was prescribed to group 2 (n=44). The drug administration began immediately after ESWL and continued until stone expulsion was confirmed up to a maximum of 42 days after the procedure.

Results

Thirty-nine of 41 (95.1%) patients in group 1 and 40 of 43 (93.0%) patients in group 2 ultimately passed stones (p=0.96). The number of ESWL sessions was 1.34±0.65 and 1.41±0.85 in groups 1 and 2, respectively (p=0.33). The patients who required analgesics after ESWL were 8 (19.5%) in group 1 and 13 (30.2%) in group 2 (p=0.31). Visual analogue scale pain severity scores were 5.33±1.22 and 6.43±1.36 in groups 1 and 2, respectively (p=0.056). The time to stone expulsion in groups 1 and 2 was 9.5±4.8 days and 14.7±9.8 days, respectively (p=0.005). No significant adverse effects occurred.

Ureterolithiasis is one of the most common diseases managed by urologists. Conservative treatment with analgesics and oral hydration is the preferred option for patients with small stones in the lower ureter. However, the success rate of conservative treatment of ureterolithiasis depends mainly on the size and location of the stone [1]. When patients present with colic symptoms, 60% of stones are located at the ureterovesical junction, but 23.4% are located between the ureteropelvic junction and the iliac vessels. In these cases, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is preferred over conservative therapy [2]. Although ESWL is an effective, noninvasive, outpatient treatment modality, the success rate of ESWL is not as high as that of ureteroscopic lithotripsy [3]. Furthermore, renal colic caused by steinstrasse after ESWL and the prolonged treatment period are problematic [4]. To prevent these complications, ESWL combined with the administration of an alpha adrenergic receptor (AR) antagonist such as tamsulosin has shown good efficacy in treating patients with ureteral stones [5].

Alpha-1 AR antagonists decrease the tension of ureteral smooth muscle, peristaltic frequency, and amplitude of the ureter. As a result, the increased intraureteral pressure gradient created around the stone facilitates its expulsion by urinary flow.

The pharmacologic selectivity and potency of alfuzosin for the various AR subtypes differ from than that of other alpha AR antagonists such as tamsulosin, doxazosin, and terazosin [6] and the expression level of each alpha-1 AR subtype depends on the location within the ureter [7]. Few studies have been performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of alfuzosin in adjunctive therapy after ESWL and even in medical expulsive therapy (MET). We performed this study to assess the efficacy and safety of alfuzosin for treating ureter stones.

This study was a randomized, prospective, single-blind clinical trial performed between June 2010 and July 2011 in the urology department of the Eulji Medical Center. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital, and all patients enrolled in this study provided written informed consent. All patients who presented with acute ureteric colic were referred to our ESWL center through the emergency department or urology clinic. Patients with evidence of ureteral calculi on a plain kidney-ureter-bladder (KUB) X-ray, urinalysis, and physical examination were evaluated with noncontrast computed tomography to confirm radio-opaque ureteric calculi and to measure the size of the stone. Complete blood count, urine culture, renal profile, coagulation profile, and pregnancy tests were conducted. The inclusion criteria were patients with radio-opaque ureter stones of 5 to 10 mm in diameter. Patients with any of the following were excluded: radiolucent stones, paper-thin cortex, nonfunctional kidney, previous genitourinary tract surgery, elevated serum creatinine (>1.5 mg/dL), severe obesity, pregnancy, concurrent alpha-blocker/calcium channel blocker/steroid/frusemide usage, aortic or renal artery aneurysm, or contraindications to alpha AR antagonist treatment.

All patients were treated with a Comed Lithotripsy SDS-5000 (Comed Medical Systems, Seongnam, Korea) by one physician in an outpatient setting without any anesthesia. Intramuscular or intravenous administration of analgesics was used for pain control during ESWL. The intensity of the shock waves ranged from one to three, and the frequency of the waves was about 4,000 Hz.

After ESWL, all patients were randomly divided into two groups. Group 1 received alfuzosin 10 mg (once daily) and loxoprofen sodium 68.1 mg (as needed), and group 2 received loxoprofen sodium 68.1 mg (as needed) only. Drug administration started immediately after ESWL and continued until stone expulsion was confirmed with KUB and urinalysis up to a maximum of 42 days after the procedure. Follow-up visits were scheduled weekly and included physical examinations, urinalysis, and KUB. If the ureter stone remained and was larger than 5 mm in diameter at the next follow-up visit, additional ESWL was performed. Oral hydration of at least 2 L per day was recommended to all patients. The efficacy of alfuzosin was assessed in terms of the stone-free rate, time of stone expulsion, and severity of pain compared with the analgesic-only group.

After all study steps, the data, including stone size, stone-free rate, time of stone expulsion, visual analogue scale (VAS) score of pain severity, and adverse effects, were analyzed by Student's t-test, chi-square test, and Fisher's exact test.

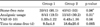

A total of 90 patients were enrolled in the study, and 84 patients completed the study. Four patients in group 1 and two patients in group 2 dropped out owing to migration or discontinuation of medications or were lost to follow-up. Age, gender, and the size and location of the ureteral stones did not differ significantly between the two groups. The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean size of the ureteral stones in groups 1 and 2 was 7.1±1.68 mm and 7.2±1.77 mm, respectively. The stone location of 35 patients in group 1 and of 37 patients in group 2 was the upper ureter.

Thirty-nine of 41 (95.1%) patients in group 1 and 40 of 43 (93.0%) patients in group 2 were stone-free by the end of the study. The stone-free rate was not significantly different between the two groups (p=0.96). The number of patients who required loxoprofen sodium for pain after ESWL was 8 (19.5%) in group 1 and 13 (30.2%) in group 2 (p=0.31). Mean VAS scores for pain severity in patients who experienced renal colic pain were 5.33±1.22 and 6.43±1.36 in groups 1 and 2, respectively (p=0.056). The numbers of ESWL sessions were 1.34±0.65 and 1.41±0.85 in groups 1 and 2, respectively (p=0.33). The mean time of stone expulsion was 9.5±4.8 days in group 1 and 18.6±20.6 days in group 2 (p=0.005) (Table 2).

No severe complications developed in either group. Mild dizziness occurred in 2 patients (4.8%) in group 1. Ejaculatory disorders such as retrograde ejaculation were not encountered.

The alpha-1 AR antagonists have been shown to be more effective than calcium channel blockers, steroids, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in aiding the expulsion of ureter stones [8-10]. The expression of alpha-1 AR is significantly higher in the distal ureter than in the proximal and mid ureter. The α-1A and α-1D AR subtypes are the most common subtypes throughout the human ureter. The distribution of the AR subtypes differs according to the location in the ureter. The α-1D AR subtype is the most common in the mid and distal ureter, whereas the α-1A and α-1D AR subtypes are similarly prevalent in the proximal ureter [11]. Tamsulosin has selective and high affinity for the α-1A and α-1D AR subtypes, and the efficacy of tamsulosin in MET or adjunctive therapy combined with ESWL has been demonstrated in several studies.

Kupeli et al. [12] evaluated the role of tamsulosin in MET of lower ureter stones. In that study, the success rate of the tamsulosin group with or without ESWL was higher than that of the control group (33.3% vs. 20% in the MET group compared with 70.8% vs. 42.2% in the adjunctive MET combined with ESWL group) and the efficacy was greater for larger stones [12]. Kobayashi et al. [13] evaluated the efficacy of low-dose tamsulosin (0.2 mg) combined with ESWL. In that study, the stone-free rate did not differ, but the time of stone expulsion was shorter in the tamsulosin group than in the control group (15.7 days in the tamsulosin group vs. 35.5 days in the control group).

In the present study, the stone-free rate after ESWL in both groups was greater than 90%, with no significant difference between the groups, but the time of stone expulsion was significantly shorter in the alfuzosin group than in the control group (9.5 days vs. 18.6 days, p=0.0005). The stone-free rates and the time of stone expulsion were better than in previous reports describing adjunctive MET combined with ESWL [5,14-16]. Our inclusion criteria, which were limited to smaller ureter stones, and the additional ESWL might explain the higher stone-free rate in the present study. Even though patients in both groups had high stone-free rates, alfuzosin may have contributed to the significant reduction in the time of stone expulsion compared with that in the control group.

There are few published reports regarding the efficacy of alfuzosin in MET. In a previous study that enrolled 76 patients to evaluate the efficacy of alfuzosin in MET, alfuzosin reduced the time to stone expulsion and pain severity, but the stone expulsion rate was not significantly improved [17]. In another study that evaluated the efficacy of alfuzosin in MET, the overall spontaneous passage rate was increased by 31.8%, with rates up to 51.3% for upper ureter stones. Alfuzosin also reduced the use of analgesics and the need for ureteroscopic lithotripsy or ESWL owing to uncontrolled renal colic pain [18]. In our study, the means of the VAS score after ESWL were 5.33±1.22 and 6.43±1.36 for the alfuzosin group and the control group, respectively. The rates of renal colic episodes after ESWL were 19.5% and 30.2%. The subjective pain scale and the rate of renal colic episodes was less in the alfuzosin group than in the control group, but the differences were not significant.

Although the basic pharmacologic effects of all alpha-1 AR antagonists are similar, the minor pharmacologic differences between alpha-1 AR antagonists may cause different efficacy and safety profiles in MET with or without ESWL.

Yilmaz et al. [19] compared the efficacies of tamsulosin, terazosin, and doxazosin in treating patients with lower ureter stones less than 10 mm in diameter. In that study, these three alpha AR antagonists showed better stone-free rates and decreased pain episodes and analgesic use compared with the control group. No significant side effects, such as severe hypotension, that required the cessation of the medication were reported in any of the AR groups, but the efficacy of alfuzosin was not compared with that of the other AR antagonists. In a study comparing the efficacy of alfuzosin and tamsulosin in treating patients with lower ureter stones, both AR antagonists showed high success rates of stone expulsion compared with a control group. Minor side effects, including headache, dizziness, and hypotension, occurred at similar rates in both groups, but 4.9% to 6.9% of patients in the tamsulosin group experienced retrograde ejaculation, which was not seen in the other groups [20,21]. In the present study, the stone expulsion rate and the incidence of minor adverse effects such as dizziness and headache were similar to the other previously published studies, and retrograde ejaculation did not occur in either group.

In a recent study that enrolled 200 male patients with lower ureteral stones less than 10 mm in diameter, the selective α-1A AR antagonist silodosin decreased the mean time to stone clearance and increased the stone expulsion rate in MET. However, 3.4% of patients in the silodosin group experienced retrograde ejaculation [22].

Tamsulosin has higher selectivity for α-1A and α-1D ARs and silodosin has higher selectivity for α-1A AR, but alfuzosin has similar selectivity for all three α-1 AR subtypes. Tamsulosin has a much stronger affinity for α-1A and α-1D ARs than do other AR blockers [23]. These strong affinities of tamsulosin and silodosin for the α-1A AR lead to a high success rate of MET and may explain why these agents cause retrograde ejaculation in young male patients [24]. The incidence of ejaculatory disorders such as retrograde ejaculation is reported to be 0% to 0.3% in patients receiving alfuzosin [25,26], whereas ejaculatory disorders occurred in 6% to 18% of patients receiving tamsulosin 0.4 or 0.8 mg [27,28]. The affinity of tamsulosin for α-1A AR plays an important role in the contraction of the vas deferens and the seminal vesicle [29,30] and may be one of the reasons patients receiving tamsulosin have an increased incidence of this effect.

In 39 of 44 patients in group 1 and 34 of 41 patients in group 2, the location of the stone was between the iliac crest and the ureteropelvic junction. The expression of alpha-1 AR is highest in the distal ureter, and the proportion of each AR subtype depends on the level within the ureter. The α-1A, -1B, and -1D ARs are found in the entire ureter irrespective of location, and the affinity of alfuzosin for all three AR subtypes is similar. We suspected that alfuzosin would facilitate stone expulsion in the upper ureter like other alpha AR antagonists do. Initially, we planned to compare the efficacy of alfuzosin depending on the location of the stone within the ureter. However, this was not possible because the number of enrolled patients with lower ureter stones was too small.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the success of ESWL could be influenced by the physician's skill. To reduce this discrepancy, all ESWL was performed by one physician who had more than 10 years of experience with performing the procedure. Second, although follow-up was performed weekly, accurate evaluation of stone expulsion time in the unit of a 'day' was not possible in clinical practice. Third, the numbers of patients were not sufficient to evaluate differences in the stone expulsion rate or time depending on the stone location in the alfuzosin group.

Adjunctive use of alfuzosin in combination with ESWL was effective for reducing the time to stone expulsion in patients with 5 to 10 mm ureteral stones without major adverse effects. Alfuzosin after ESWL facilitates stone expulsion, but no significant improvement was demonstrated in terms of the stone-free rate or subjective pain severity scale.

References

1. Segura JW, Preminger GM, Assimos DG, Dretler SP, Kahn RI, Lingeman JE, et al. Ureteral Stones Clinical Guidelines Panel summary report on the management of ureteral calculi. The American Urological Association. J Urol. 1997. 158:1915–1921.

2. Eisner BH, Reese A, Sheth S, Stoller ML. Ureteral stone location at emergency room presentation with colic. J Urol. 2009. 182:165–168.

3. Kijvikai K, Haleblian GE, Preminger GM, de la Rosette J. Shock wave lithotripsy or ureteroscopy for the management of proximal ureteral calculi: an old discussion revisited. J Urol. 2007. 178(4 Pt 1):1157–1163.

4. Sayed MA, el-Taher AM, Aboul-Ella HA, Shaker SE. Steinstrasse after extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy: aetiology, prevention and management. BJU Int. 2001. 88:675–678.

5. Resim S, Ekerbicer HC, Ciftci A. Role of tamsulosin in treatment of patients with steinstrasse developing after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Urology. 2005. 66:945–948.

6. Kobayashi S, Tomiyama Y, Maruyama K, Hoyano Y, Yamazaki Y, Kusama H. Effects of four different alpha(1)-adrenoceptor antagonists on alpha-adrenoceptor agonist-induced contractions in isolated mouse and hamster ureters. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2009. 45:187–195.

7. Park HK, Choi EY, Jeong BC, Kim HH, Kim BK. Localizations and expressions of alpha-1A, alpha-1B and alpha-1D adrenoceptors in human ureter. Urol Res. 2007. 35:325–329.

8. Hollingsworth JM, Rogers MA, Kaufman SR, Bradford TJ, Saint S, Wei JT, et al. Medical therapy to facilitate urinary stone passage: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006. 368:1171–1179.

9. Parsons JK, Hergan LA, Sakamoto K, Lakin C. Efficacy of alpha-blockers for the treatment of ureteral stones. J Urol. 2007. 177:983–987.

10. Singh A, Alter HJ, Littlepage A. A systematic review of medical therapy to facilitate passage of ureteral calculi. Ann Emerg Med. 2007. 50:552–563.

11. Itoh Y, Kojima Y, Yasui T, Tozawa K, Sasaki S, Kohri K. Examination of alpha 1 adrenoceptor subtypes in the human ureter. Int J Urol. 2007. 14:749–753.

12. Kupeli B, Irkilata L, Gurocak S, Tunc L, Kirac M, Karaoglan U, et al. Does tamsulosin enhance lower ureteral stone clearance with or without shock wave lithotripsy? Urology. 2004. 64:1111–1115.

13. Kobayashi M, Naya Y, Kino M, Awa Y, Nagata M, Suzuki H, et al. Low dose tamsulosin for stone expulsion after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: efficacy in Japanese male patients with ureteral stone. Int J Urol. 2008. 15:495–498.

14. Falahatkar S, Khosropanah I, Vajary AD, Bateni ZH, Khosropanah D, Allahkhah A. Is there a role for tamsulosin after shock wave lithotripsy in the treatment of renal and ureteral calculi? J Endourol. 2011. 25:495–498.

15. Wang H, Liu K, Ji Z, Li H. Effect of alpha1-adrenergic antagonists on lower ureteral stones with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Asian J Surg. 2010. 33:37–41.

16. Gravas S, Tzortzis V, Karatzas A, Oeconomou A, Melekos MD. The use of tamsulozin as adjunctive treatment after ESWL in patients with distal ureteral stone: do we really need it? Results from a randomised study. Urol Res. 2007. 35:231–235.

17. Pedro RN, Hinck B, Hendlin K, Feia K, Canales BK, Monga M. Alfuzosin stone expulsion therapy for distal ureteral calculi: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Urol. 2008. 179:2244–2247.

18. Chau LH, Tai DC, Fung BT, Li JC, Fan CW, Li MK. Medical expulsive therapy using alfuzosin for patient presenting with ureteral stone less than 10 mm: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Int J Urol. 2011. 18:510–514.

19. Yilmaz E, Batislam E, Basar MM, Tuglu D, Ferhat M, Basar H. The comparison and efficacy of 3 different alpha1-adrenergic blockers for distal ureteral stones. J Urol. 2005. 173:2010–2012.

20. Ahmed AF, Al-Sayed AY. Tamsulosin versus alfuzosin in the treatment of patients with distal ureteral stones: prospective, randomized, comparative study. Korean J Urol. 2010. 51:193–197.

21. Cha WH, Choi JD, Kim KH, Seo YJ, Lee K. Comparison and efficacy of low-dose and standard-dose tamsulosin and alfuzosin in medical expulsive therapy for lower ureteral calculi: prospective, randomized, comparative study. Korean J Urol. 2012. 53:349–354.

22. Itoh Y, Okada A, Yasui T, Hamamoto S, Hirose M, Kojima Y, et al. Efficacy of selective α1A adrenoceptor antagonist silodosin in the medical expulsive therapy for ureteral stones. Int J Urol. 2011. 18:672–674.

23. Richardson CD, Donatucci CF, Page SO, Wilson KH, Schwinn DA. Pharmacology of tamsulosin: saturation-binding isotherms and competition analysis using cloned alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes. Prostate. 1997. 33:55–59.

24. Grasso M, Fortuna F, Lania C, Blanco S. Ejaculatory disorders and alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonists therapy: clinical and experimental researches. J Transl Med. 2006. 4:31.

25. Roehrborn CG, Van Kerrebroeck P, Nordling J. Safety and efficacy of alfuzosin 10 mg once-daily in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms and clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia: a pooled analysis of three double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. BJU Int. 2003. 92:257–261.

26. Hofner K, Jonas U. Alfuzosin: a clinically uroselective alpha1-blocker. World J Urol. 2002. 19:405–412.

27. Lepor H. Phase III multicenter placebo-controlled study of tamsulosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Tamsulosin Investigator Group. Urology. 1998. 51:892–900.

28. Narayan P, Bruskewitz R. A comparison of two phase III multicenter, placebo-controlled studies of tamsulosin in BPH. Adv Ther. 2000. 17:287–300.

29. Moriyama N, Nasu K, Takeuchi T, Akiyama K, Murata S, Nishimatsu H, et al. Quantification and distribution of alpha 1-adrenoceptor subtype mRNAs in human vas deferens: comparison with those of epididymal and pelvic portions. Br J Pharmacol. 1997. 122:1009–1014.

30. Giuliano F, Allard F, McKenna K, Jardin A, Benoit G, Bernabe J. Tamsulosin has more deleterious effects than alfuzosin on parameters characterizing ejaculation in anaesthetized rats [abstract]. Int J Impot Res. 2002. 14:suppl 3. S12.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download