Abstract

Retrograde cystography and computed tomography (CT) are considered the gold standard for investigating bladder and pelvic bone injury. However, these methods can miss extraperitoneal bladder rupture caused by a penetrating bone fragment from a pelvic bone fracture. We experienced a routine conventional cystography and CT scan that failed to identify penetration of the bladder by a bone fragment, which thus delayed optimal treatment. Therefore, different diagnostic methods such as CT cystography or cystoscopy should be considered to rule out penetrating injury by a bony fragment in patients with extraperitoneal bladder rupture.

The incidence of bladder rupture associated with a pelvic fracture is reported to range from 5 to 10% [1]. Most bladder ruptures are of the extraperitoneal type. Although extraperitoneal bladder rupture is usually treated conservatively, extraperitoneal bladder rupture with a penetrating bony fragment within the bladder lumen requires surgical repair and drainage of the perivesical space.

Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of bladder trauma may increase patient morbidity and mortality. Therefore, rapid diagnosis is essential for optimal patient management.

Early and exact diagnosis of extraperitoneal bladder ruptures with a penetrating bony fragment is essential for optimal patient management. Although conventional retrograde cystography has been considered the gold standard for evaluating bladder trauma in such patients, it cannot provide information regarding other pelvic structures and is sometimes limited by the presence of overlying fracture fragments or fixation devices. Some extraperitoneal bladder ruptures caused by a bone fragment are thus sometimes missed in the initial diagnosis, which can result in serious complications such as persistent urinary leakage, pelvic abscess, peritonitis, respiratory difficulties, and sepsis from infected urine.

We experienced a case of pelvic bone fracture with bladder rupture in which diagnosis of a spike protruding into the urinary bladder was initially missed by use of cystography, which therefore delayed treatment.

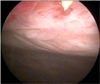

A 33-year-old female patient who was in a traffic accident was transferred to the emergency room. Plain pelvic radiography showed a complex pelvic ring fracture. After a urethral Foley catheter was inserted, gross hematuria was evacuated. The abdomen-pelvis CT scan showed 2.7-cm and 1.1-cm lacerations in the right lobe of the liver, direct contusion to the pancreas and retroperitoneal portion of the duodenum, a comminuted fracture in both the sacral ala and ischium, and a moderate amount of fluid collection in the perivesical space, which suggested extraperitoneal bladder rupture (Fig. 1). We confirmed the extraperitoneal bladder rupture near the bladder neck by use of cystography (Fig. 2). Because of her multiple organ injuries, the patient underwent conservative treatment of the fractures with placement of an indwelling bladder catheter until healing of the extraperitoneal bladder injury. Two weeks later, repeated cystography was performed, which showed no leakage of the contrast materials. However, the urethral Foley catheter was kept in place because the patient required absolute bed rest owing to her pelvic bone fracture. After 30 days of hospitalization, the patient complained of lower abdominal discomfort; pyuria was shown on urine analysis and the patient had a febrile episode. The repeated abdominal CT scan showed complete absorption of urine in the perivesical space except on a small bladder stone. We performed cystoscopy to remove the bladder stone and at that time discovered the perforation of the anterior bladder wall by the bone fragment (Fig. 3). We excised the perforating bone fragment and repaired the perforated bladder wall by a suprapubic surgical approach (Fig. 4). The pelvic bone fracture and the bladder rupture were completely healed without any complication at the 6-month follow-up.

Bladder rupture is an excellent marker for severe trauma, and approximately 90% of patients with a traumatic bladder rupture have an associated pelvic fracture [1]. Furthermore, the presence of an associated bladder rupture remains significant, as the reported mortality rate among patients with bladder rupture after blunt trauma is substantial. Bladder ruptures that occur extraperitoneally are typically seen along the anterolateral wall, whereas intraperitoneal ruptures usually involve the dome of bladder. Bladder injuries have typically been thought to occur through 3 mechanisms: direct laceration by fracture fragments, rupture through increased hydrostatic pressure, or shearing forces transmitted by the puboprostatic or pubovesical ligament [2]. Nevertheless, it has been noted in other studies that the location of bladder rupture corresponds to the fracture location in only 35% of patients, which thus casts some doubt on laceration by fracture fragments as a common mechanism of bladder injury [3]. Furthermore, recent literature has shown that the pattern of injury to the soft tissue envelope and specifically to the ligament supporting the lower urinary tract offers the best correlation with the observed lower urinary tract injury [4]. The mechanism in this case may have been a direct laceration by fracture fragments or, less likely, by attritional compromise from chronic erosion of the bladder wall from the bony edges or subsequent iatrogenic perforation during mobilization.

Retrograde or stress cystography is well known to be highly accurate for diagnosing bladder rupture [5]. The bladder should be filled in cooperative and conscious patients to a sense of discomfort, otherwise to 350 ml. For a plain film technique, three images are obtained: one before administration of a contrast agent, one full-bladder anteroposterior film, and one drainage film. Posterior extravasation of the contrast medium can be missed without a drainage film. In our patient, we followed this protocol and we detected the bladder rupture. If we had obtained a full-bladder oblique or lateral film, we may have suspected the direct laceration by a fracture fragment. However, we could not perform this procedure because of the patient's complex pelvic bone fracture and hemodynamic instability.

Nowadays, CT cystography is now frequently selected as a more efficient means of assessing the bladder [6]. CT cystography has several advantages over retrograde cystography, such as allowing the simultaneous assessment of multiple organ systems and shortening the preoperative evaluation of trauma patients. Moreover, conventional cystography is sometimes difficult in a trauma setting, and turning a patient with pelvic trauma may not be possible and is sometimes limited by the presence of the overlying fracture fragment. In our patient, we did not use CT cystography because this diagnostic modality takes a relatively long time to perform and requires a compliant and stable trauma patient. If we had performed CT cystography at the time of the trauma, we would have detected the direct laceration by the fracture fragments and we could have decided on a proper management plan. Therefore, we believe that CT cystography may be helpful if a patient has a complex pelvic bone fracture with gross hematuria.

In conclusion, in patients with bladder rupture with multiple pelvic bone fractures, the possibility of a penetrating injury by a bony fragment must be considered. Cystography does not in itself seem to reliably exclude such injury. We recommend CT cystography and cystoscopy to rule out penetrating injury by a bony fragment in patients with extraperitoneal bladder rupture with complex pelvic bone fracture, because surgical repair, not conservative therapy, is the gold standard of care in these cases.

Figures and Tables

| FIG. 1Pelvic bone 3D reconstruction computed tomography showed a comminuted fracture in both sacral ala involving both the sacral foramen and the left sacroiliac joint, multifocal fractures in both superior pubic rami and both inferior pubic rami, and a comminuted fracture in the left acetabulum, anterior wall. |

References

1. Heetveld MJ, Poolman RW, Heldeweg EA, Ultee JM. Spontaneous expulsion of a screw during urination: an unusual complication 9 years after internal fixation of pubic symphysis diastasis. Urology. 2003. 61:645.

2. Avey G, Blackmore CC, Wessells H, Wright JL, Talner LB. Radiographic and clinical predictors of bladder rupture in blunt trauma patients with pelvic fracture. Acad Radiol. 2006. 13:573–579.

3. Carroll PR, McAninch JW. Major bladder trauma: mechanisms of injury and a unified method of diagnosis and repair. J Urol. 1984. 132:254–257.

4. Andrich DE, Day AC, Mundy AR. Proposed mechanisms of lower urinary tract injury in fractures of the pelvic ring. BJU Int. 2007. 100:567–573.

5. Carroll PR, McAninch JW. Major bladder trauma: the accuracy of cystography. J Urol. 1983. 130:887–888.

6. Chan DP, Abujudeh HH, Cushing GL Jr, Novelline RA. CT cystography with multiplanar reformation for suspected bladder rupture: experience in 234 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006. 187:1296–1302.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download