Abstract

Purpose

Controversy exists over the pain during prostate biopsy. Periprostatic nerve block is a commonly used anaesthetic technique during transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided prostate biopsy. The recent trend toward increasing the number of cores has become popular. This practice further increases the need for a proper anaesthetic application. We compared the efficacy of periprostatic nerve block with or without intraprostatic nerve block.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a prospective double-blinded placebo-controlled study at our institute with 142 consecutive patients. Patients were randomly assigned into 3 groups. Group 1 received periprostatic nerve block with intraprostatic nerve block with 1% lignocaine. Group 2 patients were administered periprostatic nerve block only with 1% lignocaine. Group 3 received no anaesthesia. Patients were asked to grade their level of pain by using an 11-point linear analogue scale at the time of ultrasound probe insertion, at the time of anaesthesia, during biopsy, and 30 minutes after biopsy.

Results

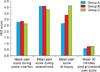

The study groups were comparable in demographic profile, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, and prostate size. The mean pain scores at the time of biopsy in groups 1, 2, and 3 were 2.70, 3.39, and 4.16, respectively. Group 1 recorded the minimum mean pain score of 2.70 during prostate biopsy, which was significantly lower than the scores of groups 2 and 3 (p<0.001). There were no significant differences in pain scores among the 3 groups during probe insertion, during anaesthesia, or at 30 minutes after biopsy (p>0.05).

Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided biopsy has become the standard procedure for diagnosing prostatic carcinoma. Histological diagnosis is mandatory before initiating any kind of treatment of prostatic carcinoma, and TRUS-guided biopsy is the only way to achieve this. In recent years, a consensus has been reached that sextant sampling is inadequate, and sampling with 8 cores or greater has been suggested [1]. These extended techniques allow us to obtain more biopsy samples and increase the prostate cancer detection rate. This increased number of cores translates to increased pain scores, however, if no analgesia is given; this concept is called cumulative pain by Kaver et al. [2].

Studies show that almost 20% of patients report that pain is significant and that they would refuse rebiopsy without analgesia [1]. Men scheduled for TRUS-guided biopsy experience considerable psychological stress. The reasons for this stress are manifold and include fear of diagnosis of cancer, the anal route of penetration, that the examined organ is part of the male sexual system, and the anticipated pain during the procedure. Although most of the morbidities are minor, they are traumatic and worrisome to the patient. Crundwell et al. [3] found moderate to severe pain scores during prostate biopsy in his patients. It is well known that anxiety is common in men before and during the procedure. Those people who are anxious experience higher pain scores, as in young people. Similarly, patients having a past unpleasant experience have higher pain scores.

Various modalities have been described in the literature for giving analgesia during TRUS-guided prostate biopsy, but no standard technique has proved to be most effective. In recent times, periprostatic nerve block has emerged as a standard technique for prostate biopsy, but it has been shown by various authors that it is a significant yet insufficient method. This led to combining other analgesics with periprostatic nerve block, such as tramadol or intraprostatic nerve block. However, only a few studies are available and more studies are needed to reach any consensus. In this study, we compared analgesia with periprostatic nerve block alone versus periprostatic nerve block with intraprostatic nerve block in TRUS-guided prostate biopsy.

This prospective randomized controlled trial comparing periprostatic nerve block with or without intraprostatic block was done in total of 142 patients at the Department of Urology, Pandit Bhagwat Dayal Sharma University of Health Sciences in collaboration with the Department of Radiodiagnosis between June 2010 and September 2011. The patients were randomly assigned by use of the card method. Patients were asked to pick an envelope from three packs of opaque, sealed envelopes. Drugs were grouped according to the number on the envelope. The urologist doing the biopsy was unaware of the grouping. He then used drugs from the numbered drugs (without information about the content) according to the number on the envelope. The drug was prepared by a fellow who was unaware of the study protocol per the envelope selected. After the biopsy was completed, the patients were shown a visual analogue scale and were asked to mark their pain score on the scale.

Patients having an elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level (>4 ng/ml) and abnormal digital rectal examination results (discrete nodule, focal induration, a diffusely hard prostate) were included in this study.

Patients having a history of previous biopsy, chronic prostatitis, chronic pelvic pain, inflammatory bowel disease, anorectal problems, active urinary tract infections, or local anesthetic allergy were excluded from this study.

Informed consent was obtained prior to the procedure. All patients were given a phosphatidyl choline enema 1 hour before the procedure. Administration of prophylactic antibiotics around the time of the biopsy was started 1 day before in the form of ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day for 3 days to prevent infection.

A digital rectal examination with lubricating jelly was performed prior to insertion of the probe to rule out any rectal pathology that would contraindicate insertion of the probe and to allow the identification of any palpable prostatic abnormalities to which special attention could be paid during ultrasound examination with an MDI 5000 Sono CT (Philips, Beckley, WV, USA).

All patients were assigned to one of three groups randomly. The three groups, A, B, and C, included 47, 46, and 49 patients, respectively.

Group A (nerve block with intraprostatic nerve block): nerve block using 5 ml 1% lignocaine (Lox 2% Neon Laboratories, Mumbai, India) was injected just lateral to the junction between the prostate base and seminal vesicle just before biopsy. The probe was adjusted to the sagittal plane with the on-screen biopsy guide operational before placement. A 22-gauge, 7-inch spinal needle was placed through the biopsy guide channel under ultrasound guidance into the area where the prostatic innervation enters the gland through the guide fitted on probe. The probe was angled laterally until the notch between the prostate and the seminal vesicle was visualized and 1% lignocaine (5 ml) was injected on each side. Successful placement of the needle was confirmed when the injectate caused a separation of the seminal vesicles and prostate from the rectal wall, called the ultrasonic wheal. After this, 5 ml of 1% lignocaine was administered by use of an intraprostatic injection technique. This involved direct prostatic injection under ultrasound guidance on both sides near the base.

Group B (nerve block without intraprostatic nerve block): same as group A expect 0.9% NaCl was used for intraprostatic injection.

Group C (control): patients were not given any kind of analgesia. Instead, 0.9% NaCl was used for both injections.

The patients were positioned in the left lateral decubitus position (lying on the left side). This allowed for easier insertion of the rectal probe. The probe was gently advanced into the rectum to the base of the bladder until the seminal vesicles were visualized. Transverse images were then obtained as the probe was moved back from the prostate base to the prostate apex. Prostate volume was calculated with the transducer at the largest cross-sectional image in the transverse plane and in the mid-sagittal plane.

An 18-gauge and 20-cm biopsy needle (Bard Max-core biopsy needle, Bard Biopsy Systems, Tempe, AZ, USA) loaded in a spring-action automatic biopsy device was used to procure 12 prostate core biopsy specimens. The needle was introduced through the needle guide fitted over the probe under ultrasound guidance. The area of interest was viewed and biopsies were taken under ultrasound guidance.

After the biopsies were completed, the patients were shown a 10-cm visual analogue scale and were asked to report their pain score twice at the following times: 1) at the time of probe insertion, 2) at the time of anaesthesia, and 3) at the time of taking the biopsy. The patients were then asked to rest for 30 minutes and were asked about their pain after 30 minutes on the same scale.

The study groups were comparable in demographic profile, PSA, and prostate size (Fig. 1). The mean pain scores in group 1 during probe insertion, during anaesthesia, during biopsy, and 30 minutes after biopsy were 2.8±0.85, 4.11±1.07, 2.70±0.86, and 0.62±0.79, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 2). The mean pain scores in group 2 during probe insertion, during anaesthesia, during biopsy, and 30 minutes after biopsy were 2.89±1.02, 4.13±1.41, 3.39±0.91, and 0.78±0.76, respectively. The mean pain scores in group 3 during probe insertion, during anaesthesia, during biopsy, and 30 minutes after biopsy were 2.69±0.77, 3.84±0.85, 4.16±0.96, and 0.82±0.78, respectively. Group 1 recorded the minimum mean pain score of 2.70 during prostate biopsy, which was significantly lower than the scores of groups 2 and 3 (p<0.001). There were no significant differences in pain scores among the 3 groups during probe insertion, during anaesthesia, and 30 minutes after biopsy (p>0.05). The same results were recorded by ANOVA (Table 2). The complications experienced were bacteremia, rectal bleeding, hematuria, fever, pain during voiding, hematospermia, and urine retention. There were 34 complications in group A, 36 in group B, and 41 in group C; the number of complications may have been more than 1 in any given patient. All complications were minor and were managed on an outpatient basis without admission. All three groups were comparable in terms of complications. There was no significant difference in the cancer detection rate in the 3 groups. The cancer detection rate was the same in all groups.

Although TRUS-guided prostate biopsy is safe, patients experience significant discomfort during the procedure [4]. Pain associated with TRUS-guided prostate biopsy is important, because many patients must undergo rebiopsy and pain may prevent them from doing so.

Pain is a complex perceptual experience that is difficult to quantify. This pain is a translation of actual somatic and visceral pain, anxiety, and psychological stress and thus the interpretation of scores remains subjective. In the report of Desgrandchamps et al. [5], patients were asked to score their severity of discomfort at the end of the procedure by use of a self-administered verbal rating scale that consisted of a list of adjectives describing different levels of pain, from none to intolerable pain. A linear 11-point visual analogue scale is easily comprehensible and easy to demonstrate and remains the most established method of scoring pain. Others have modified it and used it in various ways.

Pain during prostate biopsy results from insertion of the ultrasound probe and needle puncture into the prostate. The nerve supply of the prostate is autonomic and originates from the inferior hypogastric plexus. The nerves pass along the plane between the rectum and prostatic capsule. The pain associated with prostate biopsy is thought to be contributed to by direct contact of the biopsy needle with these nerves within the stroma and the prostatic capsule, which are richly innervated [6].

Conde et al. [7] in 2006 found that bilateral periprostatic nerve block is better for analgesia than oral morphine. Over the years, it has been established by various authors that periprostatic nerve block is very effective for TRUS-guided prostate biopsy. Since its introduction by Nash et al. [8], this technique has gone further to the extent of being the gold standard technique in prostate biopsy. Various authors have found it to be very effective in comparison with placebo, control, and other analgesic methods [8-11].

The issue is far from settled, however, as others have found the procedure to still be very painful. Wu et al. [12] proposed that periprostatic nerve block is not effective for prostatic biopsy. Bozlu et al. [13] proposed in 2004 that periprostatic lidocaine infiltration and tramadol have no analgesic effect during prostate biopsy.

Thus, a need for better analgesics was realized. In 2005 Mutaguchi et al. [14] proposed a new intraprostatic analgesia technique for anesthetizing the prostate that requires blocking all sensory nerves from the posterior and anterior sides. They found that 71 patients out of 170 patients had a mean pain score of 1.9 as compared to 2.6 with of periprostatic nerve block. This was found to be clinically significant. We also found a similar result but with the combination of periprostatic nerve block and intraprostatic nerve block.

Cam et al. [15] also reported that combining intraprostatic local anesthetic and periprostatic nerve block is an effective form of analgesia. They used this technique in 100 patients and found it to be very effective with a mean pain score of 0.75 compared with 2.17 for periprostatic nerve block alone. In our study we found a similar result.

In 2007, Lee et al. [16] published the results of their study in which they divided 152 patients into three groups. One group received periprostatic nerve block alone, another received intraprostatic nerve block alone, and the third received both. They found that the group with both periprostatic nerve block and intraprostatic nerve block had the best pain control at the time of anaesthesia and biopsy, and the difference was statistically significant. In our study, a significant pain difference was found only at the time of biopsy.

Moinzadeh et al. [17] assessed the use of prebiopsy outpatient analgesia using the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent rofecoxib (Vioxx). Thirty-seven percent of patients receiving placebo and 42% of patients receiving rofecoxib had significant pain (5 or greater on the visual analogue pain scale). The median pain score of patients receiving rofecoxib (4.0) versus placebo (4.0) was not significantly different (p=0.3139) by use of a Wilcoxon rank sum analysis. Our nerve blocking technique shows consistently lower pain scores than does placebo.

Adiyat et al. [18] reported no significant pain difference with a diclofenac patch or suppository at the time of biopsy, whereas the nerve block technique showed significant pain relief.

In our study, there was a significant reduction in the pain scores in group A and group B (p=0.000) at the time of biopsy as compared with group C. There was also a significant reduction in pain at the time of biopsy in group A compared with group B (p=0.000). Therefore, we recommend the use of intraprostatic as well as periprostatic nerve block in prostate biopsy patients.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Bingqian L, Peihuan L, Yudong W, Jinxing W, Zhiyong W. Intraprostatic local anesthesia with periprostatic nerve block for transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2009. 182:479–483.

2. Kaver I, Mabjeesh NJ, Matzkin H. Randomized prospective study of periprostatic local anesthesia during transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. Urology. 2002. 59:405–408.

3. Crundwell MC, Cooke PW, Wallace DM. Patients' tolerance of transrectal ultrasound-guided prostatic biopsy: an audit of 104 cases. BJU Int. 1999. 83:792–795.

4. Ochiai A, Babaian RJ. Update on prostate biopsy technique. Curr Opin Urol. 2004. 14:157–162.

5. Desgrandchamps F, Meria P, Irani J, Desgrippes A, Teillac P, Le Duc A. The rectal administration of lidocaine gel and tolerance of transrectal ultrasonography-guided biopsy of the prostate: a prospective randomized placebo-controlled study. BJU Int. 1999. 83:1007–1009.

6. Hollabaugh RS Jr, Dmochowski RR, Steiner MS. Neuroanatomy of the male rhabdosphincter. Urology. 1997. 49:426–434.

7. Conde Redondo C, Alonso FD, Robles SA, Del Valle GN, Castroviejo RF, Delgado MC, et al. TRUS-guided biopsy: comparison of two anesthetic methods. Actas Urol Esp. 2006. 30:134–138.

8. Nash PA, Bruce JE, Indudhara R, Shinohara K. Transrectal ultrasound guided prostatic nerve blockade eases systematic needle biopsy of the prostate. J Urol. 1996. 155:607–609.

9. Soloway MS, Obek C. Periprostatic local anesthesia before ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2000. 163:172–173.

10. Taverna G, Maffezzini M, Benetti A, Seveso M, Giusti G, Graziotti P. A single injection of lidocaine as local anesthesia for ultrasound guided needle biopsy of the prostate. J Urol. 2002. 167:222–223.

11. Matlaga BR, Lovato JF, Hall MC. Randomized prospective trial of a novel local anesthetic technique for extensive prostate biopsy. Urology. 2003. 61:972–976.

12. Wu CL, Carter HB, Naqibuddin M, Fleisher LA. Effect of local anesthetics on patient recovery after transrectal biopsy. Urology. 2001. 57:925–929.

13. Bozlu M, Atici S, Ulusoy E, Canpolat B, Cayan S, Akbay E, et al. Periprostatic lidocaine infiltration and/or synthetic opioid (meperidine or tramadol) administration have no analgesic benefit during prostate biopsy. A prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study comparing different methods. Urol Int. 2004. 72:308–311.

14. Mutaguchi K, Shinohara K, Matsubara A, Yasumoto H, Mita K, Usui T. Local anesthesia during 10 core biopsy of the prostate: comparison of 2 methods. J Urol. 2005. 173:742–745.

15. Cam K, Sener M, Kayikci A, Akman Y, Erol A. Combined periprostatic and intraprostatic local anesthesia for prostate biopsy: a double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized trial. J Urol. 2008. 180:141–144.

16. Lee HY, Lee HJ, Byun SS, Lee SE, Hong SK, Kim SH. Effect of intraprostatic local anesthesia during transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy: comparison of 3 methods in a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2007. 178:469–472.

17. Moinzadeh A, Mourtzinos A, Triaca V, Hamawy KJ. A randomized double-blind prospective study evaluating patient tolerance of transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate using prebiopsy rofecoxib. Urology. 2003. 62:1054–1057.

18. Adiyat KT, Kanagarajah P, PG A, Bhat S. Analgesia for prostate biopsy: efficacy of diclofenac patch versus diclofenac suppository as compared to placebo during prostate biopsy. Int J Nephrol Urol. 2010. 2:239–243.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download