Abstract

A 69-year-old man with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) received docetaxel and a corticosteroid. After the third cycle of docetaxel administration, he presented with dyspnea, cough, sputum, and fever of 39.2℃. The chest X-ray and chest computed tomography (CT) revealed a diffuse reticulonodular shadow in both lungs, which suggested interstitial pneumonitis. Initially, we used empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics and high-dose corticosteroids. However, his condition progressively became worse and he was transferred to the intensive care unit, intubated, and placed on mechanical ventilation. He died 4 days after hospital admission. Here we report this case of fatal interstitial pneumonitis after treatment with docetaxel for CRPC. We briefly consider docetaxel-induced pneumonitis to make physicians aware of the possibility of pulmonary toxicity so that appropriate treatment can be begun as soon as possible.

Recently, the detection of prostate cancer has rapidly increased in Korea owing to prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing. However, in many cases, prostate cancer is already of an advanced or metastatic state when diagnosed. In about 80 percent of these patients, androgen ablation reduces serum levels of PSA and relieves the symptoms. But in nearly all patients the disease eventually becomes refractory to hormone treatment, thus necessitating alternative treatment options. Recently, several large studies have reported that docetaxel is effective in terms of survival benefit as well as improving quality of life [1] and is considered as the first-line chemotherapeutic drug for patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). The main side effects of docetaxel are neutropenia, hypersensitivity reaction, stomatitis, peripheral neuropathy, and fluid retention [2]. Interstitial pneumonitis is a rare adverse effect but the mortality rate is high; thus, awareness of this toxicity is important.

Herein, we report the case of a patient with acute life-threatening interstitial pneumonitis after docetaxel therapy. We believe that this is the first case report about interstitial pneumonitis after docetaxel therapy for CRPC in Korea.

A 69-year-old man was diagnosed as having advanced prostate cancer with multiple bone metastases, and when diagnosed, his PSA was 1,149 ng/ml. He underwent both orchiectomy and maximal androgen blockade, and his PSA decreased to 3.3 ng/ml. However, 5 months later despite hormone therapy his PSA began to increase. Although at 4 weeks after the discontinuation of anti-androgen therapy we administered estramustine, his PSA still increased to 32.6 ng/ml. This treatment failure led him to further receive second-line chemotherapy with docetaxel 10 months later. His performance status was 1, and he was a nonsmoker. His pretreatment chest X-ray and lung sound were normal. According to the TAX 327 protocol, the treatment schedule consisted of intravenous docetaxel (75 mg/m2) every 3 weeks over 1 hour with premedication of prednisone 5 mg twice daily. During the first cycle, intravenous dexamethasone 20 mg was administrated before docetaxel to prevent hypersensitivity. After the second cycle of chemotherapy, the patient's PSA level decreased from 32.6 to 2.7 ng/ml. Owing to leucopenia (1×103/ul) after the second cycle of docetaxel administration, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) was injected and his leucocytes increased to 9.4×103/ul. The results of liver function tests and other laboratory findings were within normal limits.

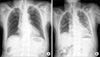

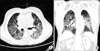

Ten days after the third cycle of docetaxel administration (cumulative dosage 350 mg), he presented to the emergency department with dyspnea, cough, sputum, and fever of 39.2℃. The physical examination revealed a mild diffuse fine crackle. The patient's leukocyte count was elevated to 13.1×103/ul, and a blood gas obtained on 5 l/min of nasal O2 demonstrated a pH of 7.422, pCO2 of 21.4 mmHg, and pO2 of 58.3 mmHg. The chest X-ray and chest computed tomography revealed diffuse reticulonodular shadow in both lungs, which suggested interstitial pneumonitis (Figs. 1, 2). Sputum and blood cultures were negative for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), nocardia, and common bacteria. Although the cultures and stains for infectious etiologies were negative, empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics and high-dose corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 500 mg per day) were used initially. Empiric therapy was expanded to include vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and piperacillin/tazobactam. Bronchoscopy and pulmonary lavage (BAL) were scheduled but his condition rapidly worsened and the invasive procedure was refused by his son. Septic shock developed after 3 days of admission. His O2 saturation decreased to 80%, and he was transferred to the intensive care unit, intubated, and placed on mechanical ventilation. Dopamine was required for hypotension. His situation worsened steadily. We performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation but he died 4 days after hospital admission.

Docetaxel is a taxane antineoplastic agent and inhibits tumor growth by inducing microtubule stabilization and promoting bcl-2 inactivation, thereby sensitizing malignant cells to apoptotic stimuli [3]. According to large randomized studies, docetaxel not only provides palliative benefits but also improves survival in CRPC patients [1]. On the basis of this evidence, docetaxel has been widely accepted as a first-choice chemotherapeutic agent for managing CRPC. The main adverse effects of docetaxel are neutropenia, alopecia, asthenia, peripheral neuropathy, and peripheral edema [2,4]. Paclitaxel, the same class of taxane, is more commonly used than docetaxel to treat lung cancer, and an incidence rate of approximately 3 to 12% of interstitial pneumonitis has been reported [5]. However, pulmonary toxicity induced by docetaxel is extremely rare, and only a few cases have been reported [4,6]. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, only two cases have been reported in the case of prostate cancer [7,8]. Although we cannot explain why the pulmonary complication is rare in prostate cancer patients, there are several possibilities. First, paclitaxel, which is more commonly used for lung cancer, is mixed with cremaphore, and this complex is related to the hypersensitivity reaction. On the other hand, docetaxel is mixed in ethanol and water rather than with cremaphor; thus, hypersensitivity reactions are uncommon with docetaxel. Second, prednisolone is commonly combined with docetaxel to manage CRPC patients, and the adjuvant steroid may prevent the hypersensitivity reaction. Third, because the lung statuses of prostate cancer patients are usually better than those of lung cancer patients, serious interstitial pneumonitis may be more rarely reported than in lung cancer patients.

The mechanism of taxane-induced interstitial pneumonitis is poorly understood, but the allergic type and the cell-mediated cytotoxic type have been suggested [9]. The docetaxel-induced lung toxicity in the cases that have been reported usually occurred after the second to fourth course of chemotherapy and was usually relieved with corticosteroid therapy [6]. Therefore, a cytotoxic T-cell-mediated immunologic reaction is a more convincing mechanism. Interestingly, there is perhaps a positive relationship between the tumor response and lung injury. Our case also showed an excellent response to docetaxel therapy, and the PSA level dropped from 32.6 to 2.7 ng/ml. Unfortunately, however, the pulmonary deterioration was irreversible despite the immediate high-dose corticosteroid therapy.

Interstitial lung disease is caused by a misdirected immune or healing reaction to a number of factors, including infections of the lungs, toxins in the environment, certain medications, radiation therapy, and chronic autoimmune diseases. Therefore, numerous diagnostic tests must be performed to confirm the disease. Among them, BAL or transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB) is necessary to exclude other etiologies. BAL fluid from drug-induced IP reveals lymphocytic alveolitis, an increase in the number of total cells, an increased proportion of neutrophils and eosinophils, and a decreased CD4/CD8 ratio. A TBLB from drug-induced IP reveals edema and swelling of the alveolar septum and interstitial and alveolar mononuclear cell infiltration with intraluminal organization and aggregation of alveolar macrophages. In this case, however, we could not perform the procedure because of the patient's unstable vital signs and the denial of his son. The patient had no other underlying disease including chronic autoimmune disease or connective lung disease and thus did not take other kinds of drugs. Also, the sputum and blood culture tests were negative for the unusual infections. Given the evidence, docetaxel-induced hypersensitivity pneumonitis was diagnosed.

Although pneumonitis is a rare side effect, the mortality rate is high; thus, oncologists should be aware of it. The patients usually present with a high fever, cough, dyspnea, and diffuse lung infiltration. The symptoms develop acutely over 1 to 2 days and rapidly progress despite empiric antibiotic therapies and culminate in respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation [10]. The treatment of choice is the administration of corticosteroid therapy, usually 30 to 60 mg of prednisolone per day for 2 to 3 weeks, or 60 to 240 mg per day in more severe conditions such as acute respiratory failure with a slow and careful tapering-off period [10].

In conclusion, docetaxel-induced interstitial pneumonitis in patients with CRPC is an extremely rare complication but could be life-threatening. Therefore, physicians should take this serious fatal complication into account.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004. 351:1502–1512.

2. Fossella FV. Docetaxel in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: review of single-agent trials. Semin Oncol. 1999. 26:5 Suppl 16. 17–23.

3. Haldar S, Basu A, Croce CM. Bcl2 is the guardian of microtubule integrity. Cancer Res. 1997. 57:229–233.

4. Kunitoh H, Watanabe K, Onoshi T, Furuse K, Niitani H, Taguchi T. Phase II trial of docetaxel in previously untreated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Japanese cooperative study. J Clin Oncol. 1996. 14:1649–1655.

5. Choy H, Safran H, Akerley W, Graziano SL, Bogart JA, Cole BF. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel and concurrent radiation therapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998. 4:1931–1936.

6. Wang GS, Yang KY, Perng RP. Life-threatening hypersensitivity pneumonitis induced by docetaxel (taxotere). Br J Cancer. 2001. 85:1247–1250.

7. Read WL, Mortimer JE, Picus J. Severe interstitial pneumonitis associated with docetaxel administration. Cancer. 2002. 94:847–853.

8. Leimgruber K, Negro R, Baier S, Moser B, Resch G, Sansone S, et al. Fatal interstitial pneumonitis associated with docetaxel administration in a patient with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Tumori. 2006. 92:542–544.

9. Grande C, Villanueva MJ, Huidobro G, Casal J. Docetaxel-induced interstitial pneumonitis following non-small-cell lung cancer treatment. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007. 9:578–581.

10. Nagata S, Ueda N, Yoshida Y, Matsuda H, Maehara Y. Severe interstitial pneumonitis associated with the administration of taxanes. J Infect Chemother. 2010. 16:340–344.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download