Abstract

We herein report a case of radical nephroureterectomy and replacement of the inferior vena cava (IVC) with ahuman cadaveric aortic graft for a patient with renal pelvis transitional cell carcinoma associated with IVC infiltration. In advanced disease, radical surgery is essential to achieve long-term survival. This case entails the use of another treatment option among the numerous options currently available for the management of patients with advanced renal cancer associated with IVC invasion.

Primary transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis or ureter is a relatively rare condition. It accounts for less than 1% of genitourinary neoplasms and 5 to 7% of all urinary tract tumors [1,2]. Extension of transitional cell carcinomas into the vena cava is rarely reported in the literature [3]. Most data available are derived from retrospective studies, and surgery is the mainstay of treatment. Aggressive surgery to remove an inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombus is reported to be effective in prolonging survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [3,4]. However, the value of aggressive surgery in the treatment of transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis remains unclear owing to limited evidence and the aggressive course of the condition. In the case of IVC invasion, complete resection is necessary, but IVC resection presents a technical challenge.

In cases requiring surgical reconstruction, prosthetic replacement has been found to be feasible and safe. The material of choice is polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), as reported previously [5,6]. Human cadaveric aortic grafts, or cryopreserved aorta, could be an option, but their use has not yet been reported for the restoration of caval continuity.

We herein report a case of radical nephroureterectomy with IVC replacement with a human cadaveric aortic graft for a patient with renal pelvis transitional cell carcinoma with IVC invasion.

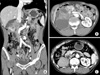

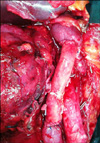

A 67-year-old man presented to our clinic with a 3-month history of dull pain in the right flank. He denied having experienced other symptoms. He had no remarkable past medical or family history. Physical examination elicited mild right costovertebral angle tenderness. Urine analysis, complete blood count, and routine blood chemistry results were unremarkable and urine cytology showed atypical cells. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated that most of the right kidney was occupied by a huge irregular tumor measuring 8 cm × 6.5 cm × 6.5 cm in size (Fig. 1A, B). The tumor exhibited heterogeneous enhancement and areas of necrosis. The right perirenal space exhibited strand-like infiltration and the right renal fascia was thickened. The tumor had invaded into the right renal vein and possibly the IVC. The right upper ureter experienced tumor invasion. Multiple, enlarged, para-aortic lymph nodes were seen. Under the impression of a renal pelvis tumor, we subsequently performed a right radical nephroureterectomy with replacement of the IVC with a human cadaveric aortic graft. The tumor was mobilized en bloc with the right kidney, adrenal gland, ureter, and regional lymph node. The right renal artery was divided and clamped on the left side of the IVC. The IVC was then clamped proximally, contralaterally, and distally and was resected for an extension of 12 cm in length. The vascular defect was then repaired with the cadaveric aortic graft (Fig. 2).

Grossly, a huge, grayish, solid tumor measuring 8.1 cm × 6.5 cm in dimension was seen involving the whole renal pelvis and calyces. The tumor had invaded the renal parenchymal, perinephric, and peripelvic fat. Renal vein and IVC involvement were also identified (Fig. 3). Microscopically, the renal tumor was classified as grade III transitional cell carcinoma (World Health Organization classification) and comprised neoplastic cells arranged in irregular solid nests associated with marked tumor necrosis. The two dissected hilar lymph nodes harbored carcinoma metastasis. The patient was discharged on the eighth postoperative day and anticoagulant therapy was initiated, which was continued for 9 months. There was no sign of recurrence at 9 months after the operation (Fig. 1C).

Invasion of the renal vein and IVC by RCC is commonly described. However, venous infiltration by transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis remains rarely reported [1-3]. Few renal pelvic tumors extend into the IVC, and it is very rare that they invade the wall of the IVC [3].

Earlier presentation of many of these transitional cell lesions due to hematuria may be partly responsible [1]. When a patient presents with signs and symptoms such as lower-extremity edema, varicocele, albuminuria, pulmonary embolism, or urographic dysfunction of the involved kidney, tumor extension into the IVC should be suspected before removing the renal tumor [1-5]. Nevertheless, the majority of patients with extension of tumor into the renal vein and IVC are asymptomatic, and the diagnosis is usually made radiologically [1-3,7].

In the case of tumor invasion of the caval wall, medial venotomy carries a higher risk of narrowing after caval wall excision and renal vein repair and often requires caval wall reconstruction. If collateral circulation is not present, IVC resection can be associated with severe edema of the lower extremities [7]. In this setting, reconstructing the IVC should be considered and can be performed with a PTFE graft, but the main concern with prosthetic grafts for vein replacement is higher risks of thrombosis and infection. Therefore, autologous venous and pericardial grafts are preferred [8].

The operative procedure depends on correct preoperative diagnosis. Urine cytology and brushings from the involved renal pelvis may aid in correct diagnosis, although a frozen section of the tumor upon removal of the specimen may be necessary to exclude transitional cell carcinoma. Similarly to the case of RCC, aggressive surgical treatment is indicated in all patients with renal tumors associated with IVC invasion, because nephrectomy alone is associated with dismal prognosis [3,4]. However, IVC resection is an uncommon and challenging procedure.

Recently, a multitude of advancements have made the IVC resection procedure safer. Advances in surgical technique and intraoperative monitoring all contribute to improved perioperative outcome. Cardiopulmonary bypass may minimize bleeding from the operation field and achieve stable hemodynamic status during IVC clamping and thus provides a bloodless operative field to facilitate tumor resection and venous reconstruction in patients with IVC invasion [9]. However, cardiopulmonary bypass is the main cause of the complex systemic inflammatory response, which leads to adverse postoperative outcomes, including renal, pulmonary, and neurological complications [10]. Postoperative bleeding and coagulation disturbances are the most frequently reported complications in patients who undergo IVC thrombectomy with nephrectomy. Another technique that may achieve hemodynamic stability is aortic cross-clamping during IVC reconstruction [9]. Even patients without venous occlusion tolerate this procedure without experiencing significant hemodynamic instability, and transient hypotension can be managed by fluid and blood replacement.

Different IVC replacement methods have been reported. Primary repair or prosthetic or biologic patch angioplasty is used in IVC partial resections. When the IVC needs to be replaced, PTFE prosthetic grafts are usually used [5,6]. Because of low venous pressure, ring-reinforced PTFE grafts are often preferred. However, the limits of this well-established technique include the risk of prosthetic occlusion or infection [5,6]. Aortic graft availability is scant because harvesting from multi-organ donors is not a standard procedure. However, an aortic graft has the advantages of being a good size-match to the vascular defect with resistance to infection. The long-term patency of IVC reconstruction is still in question, because no cases have previously been reported. Postoperative anticoagulation is not commonly described. However, we elected to initiate post-operative anticoagulation, which continued for 9 months, to ensure patency of the aortic graft.

Long-term follow-up will be necessary to monitor graft survival. In this report, the feasibility and safety of the procedure is documented. If safety, efficacy, and long-term patency were to be validated, a regular collection of large vessels by donor surgical teams should be encouraged to facilitate the conduct of prospective studies.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Hall MC, Womack S, Sagalowsky AI, Carmody T, Erickstad MD, Roehrborn CG. Prognostic factors, recurrence, and survival in transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: a 30-year experience in 252 patients. Urology. 1998. 52:594–601.

2. Kirkali Z, Tuzel E. Transitional cell carcinoma of the ureter and renal pelvis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003. 47:155–169.

3. Fujimoto M, Tsujimoto Y, Nonomura N, Kojima Y, Miki T, Ariyoshi H, et al. Renal pelvic cancer with tumor thrombus in the vena cava inferior. A case report and review of the literature. Urol Int. 1997. 59:263–265.

4. Al Otaibi M, Abou Youssif T, Alkhaldi A, Sircar K, Kassouf W, Aprikian A, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena caval extention: impact of tumour extent on surgical outcome. BJU Int. 2009. 104:1467–1470.

5. Bower TC, Nagorney DM, Cherry KJ Jr, Toomey BJ, Hallett JW, Panneton JM, et al. Replacement of the inferior vena cava for malignancy: an update. J Vasc Surg. 2000. 31:270–281.

6. Hardwigsen J, Baqué P, Crespy B, Moutardier V, Delpero JR, Le Treut YP. Resection of the inferior vena cava for neoplasms with or without prosthetic replacement: a 14-patient series. Ann Surg. 2001. 233:242–249.

7. Montie JE, el Ammar R, Pontes JE, Medendorp SV, Novick AC, Streem SB, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with inferior vena cava tumor thrombi. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991. 173:107–115.

8. Caldarelli G, Minervini A, Guerra M, Bonari G, Caldarelli C, Minervini R. Prosthetic replacement of the inferior vena cava and the iliofemoral vein for urologically related malignancies. BJU Int. 2002. 90:368–374.

9. Jibiki M, Iwai T, Inoue Y, Sugano N, Kihara K, Hyochi N, et al. Surgical strategy for treating renal cell carcinoma with thrombus extending into the inferior vena cava. J Vasc Surg. 2004. 39:829–835.

10. Bissada NK, Yakout HH, Babanouri A, Elsalamony T, Fahmy W, Gunham M, et al. Long-term experience with management of renal cell carcinoma involving the inferior vena cava. Urology. 2003. 61:89–92.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download