1. Lepor H. Pathophysiology of lower urinary tract symptoms in the aging male population. Rev Urol. 2005. 7:Suppl 7. S3–S11.

2. Homma Y, Kawabe K, Tsukamoto T, Yamanaka H, Okada K, Okajima E, et al. Epidemiologic survey of lower urinary tract symptoms in Asia and Australia using the international prostate symptom score. Int J Urol. 1997. 4:40–46.

3. Baazeem A, Elhilali MM. Surgical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia: current evidence. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008. 5:540–549.

4. AUA guideline on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (2003). Chapter 1: diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J Urol. 2003. 170(2 Pt 1):530–547.

5. Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, Emberton M, Gravas S, Michel MC, et al. Guidelines on the Treatment of Non-neurogenic Male LUTS. 2011. European Association of Urology.

6. Barendrecht MM, Koopmans RP, de la Rosette JJ, Michel MC. Treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia: the cardiovascular system. BJU Int. 2005. 95:Suppl 4. 19–28.

7. Watson V, Ryan M, Brown CT, Barnett G, Ellis BW, Emberton M. Eliciting preferences for drug treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004. 172(6 Pt 1):2321–2325.

8. Lee E, Lee C. Clinical comparison of selective and non-selective alpha 1A-adrenoreceptor antagonists in benign prostatic hyperplasia: studies on tamsulosin in a fixed dose and terazosin in increasing doses. Br J Urol. 1997. 80:606–611.

9. Lee ES, Lee CW. Effect of tamsulosin, a selective alpha1A-adrenoreceptor antagonist, in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Korean J Urol. 1997. 38:158–166.

11. Barry MJ, Williford WO, Change Y, Machi M, Jones KM, Walker-Corkey E, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association symptom index and the benign prostatic hyperplasia impact index is perceptible to patients? J Urol. 1995. 154:1770–1774.

12. Höfner K, Claes H, De Reijke TM, Folkestad B, Speakman . Tamsulosin 0.4 mg once daily: effect on sexual function in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol. 1999. 36:335–341.

14. Chen ML, Shah V, Patnaik R, Adams W, Hussain A, Conner D, et al. Bioavailability and bioequivalence: an FDA regulatory overview. Pharm Res. 2001. 18:1645–1650.

15. Shaw SJ, Krauss GL. Generic antiepileptic drugs. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2008. 10:260–268.

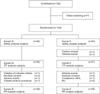

). We anticipated that about 15% of enrolled patients would be ineligible. Therefore, 122 patients (61 per study group) were recruited. All results are presented as means±standard deviations.

). We anticipated that about 15% of enrolled patients would be ineligible. Therefore, 122 patients (61 per study group) were recruited. All results are presented as means±standard deviations.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download