Abstract

Purpose

Transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy is the procedure of choice for diagnosing prostate cancer. We compared with pain-relieving effect of acetaminophen, a known drug for enhancing the pain-relieving effect of tramadol, and eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA), a local anesthetic agent, with that of the conventional periprostatic nerve block method.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective, randomized, single-blinded study. A total of 430 patients were randomly assigned to three groups. Group 1 received a periprostatic nerve block with 1% lidocaine, group 2 received acetaminophen 650 mg, and group 3 received EMLA cream for pain control. All patients were given 50 mg of tramadol intravenously 30 minutes before the procedure. At 3 hours after completion of the procedure, the patients were asked to grade their pain on a horizontal visual analogue scale (VAS). The patients were also asked whether they were willing to undergo future biopsy if required.

Results

There were no significant differences between the three groups in terms of age, prostate-specific antigen, prostate size, or numbers of biopsy cores. The pain scores for groups 2 and group 3, which were 3.47±1.92 and 3.50±1.36, respectively, were similar and were significantly lower than that of group 1, which was 5.24±2.07.

Go to :

As Korea also experiences the graying of society, awareness of prostate cancer has increased, and with the introduction of prostate-specific antigen (PSA), prostate cancer can be detected and treated early. The sensitivity of PSA to detect prostate cancer has been reported to be high. Recently, as its measurement has become standardized, the number of patients undergoing prostate biopsy is rising rapidly.

In the past, finger-guided prostate biopsy was performed. Recently, however, owing to the development of prostate ultrasonography, transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy has become the standard procedure. Transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy is essential for the definite diagnosis of prostate cancer; nonetheless, it induces pain in many cases. It has been reported that the pain is severe in approximately 19% to 25% of patients undergoing prostate biopsy [1-3]. In addition, many patients present with not only pain felt during the prostate biopsy but also pain felt during the insertion of the transrectal ultrasound probe. Furthermore, it has been reported that approximately 20% of the patients do not wish to undergo prostate biopsy again unless the pain is reduced [1]. Therefore, numerous methods have been suggested to reduce the pain during transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy [4-17]. Presently, to reduce the pain before prostate biopsy, the most widely applied method is the periprostatic nerve block method with 1% lidocaine [18]. Nonetheless, it does not sufficiently reduce pain in some cases.

Tramadol is used for the reduction of pain in many fields, and acetaminophen has been reported to augment the analgesic effects of tramadol [19]. Eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) cream (2.5% lidocaine, 2.5% prilocaine) is a topical anesthetic agent that is frequently used in the dermatologic and obstetric fields. In this study, we compared with pain-relieving effect of acetaminophen and EMLA in addition to intravenous injection of tramadol with that of the conventional periprostatic nerve block method.

Go to :

This was a prospective, single-blinded randomized study performed in a tertiary urology center. The study subjects were selected from patients who visited the department of urology at our hospital during approximately 14 months from May 2009 to June 2010. The subjects were 430 patients who underwent transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy, and all biopsies were performed by a single urologist. At the time of selection of the subjects, patients with prostatitis, chronic pelvic pain, or anal diseases such as hemorrhoids, anal fissure, and anal fistula were excluded.

By random assignment, the subjects were divided into the periprostatic nerve block group, in whom 1% lidocaine was injected (group 1); the oral acetaminophen 650 mg group (group 2); and the EMLA cream group (group 3). Thirty minutes before prostate biopsy, 50 mg tramadol was injected intravenously in all groups of patients, and 5 g of EMLA cream was applied 30 minutes before prostate biopsy to the peri-anal area and rectum in group 3. EMLA cream is known to allow dermal anesthesia and is specially applied to prevent pain associated with superficial surgical procedures. EMLA can be used under occlusive dressing. In our case, however, because the affected areas were the peri-anal area and rectum, occlusive dressing could not be applied. Regarding the number of prostate biopsy samples, 10 cores or 12 cores were obtained randomly. The transrectal ultrasound examinations were performed by using the General Electric LOGIQ400MD ultrasound machine and a 6 MHz transducer.

Three hours after prostate biopsy, by a single-blind method, a third person evaluated the pain that was felt during the insertion of the transrectal ultrasound probe by using a visual analogue scale (VAS) (Fig. 1). A score of 0 was defined as no pain, and 10 points was defined as the most severe intolerable pain. In addition, we surveyed whether the patients were willing to undergo another prostate biopsy in the future if required. After 3 days, the pain that developed during the biopsy and the presence of complications were assessed again in telephone interviews.

For the statistical program, SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. Statistical analysis was performed with ANOVA and Pearson chi-square test, and p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Go to :

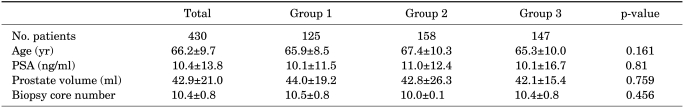

The mean age of the 430 patients was 66.2%9.7 years, the average PSA was 10.4%13.8 ng/ml, the average prostate size was 42.9%21.0 ml, and the average number of biopsy cores was 10.4%0.8. The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the three groups.

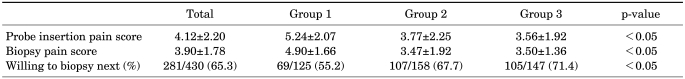

The average pain score at the time of insertion of the ultrasound probe and the pain score at the time of biopsy were 4.12%2.20 and 3.90%1.78, respectively, and the percentage of patients who indicated that they would be willing to undergo rebiopsy if needed was 65.3% (281 of 430 patients). The pain scores and willingness to undergo rebiopsy are shown in Table 2. The pain scores at the time of insertion of the ultrasound probe and at the time of biopsy were similar for group 2 and group 3. However, they were significantly lower than the pain scores of group 1 (p<0.05) (Table 2). Similarly, the percentages of patients willing to undergo rebiopsy in group 2 and group 3 were 67.6% (107/158) and 71.4% (105/147), respectively, which was significantly higher than in group 1 (55.2%; 69/125) (p<0.05).

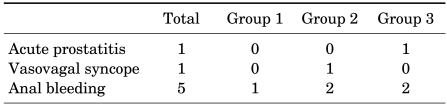

Regarding side effects that developed after prostate biopsy, there was 1 case of acute prostatitis, 1 of vasovagal, and 5 of rectal bleeding (Table 3). The patient who developed acute prostatitis in group 3 was discharged after intravenous injection of antibiotics for 2 days. The patient who developed vasovagal syncope in group 2 was stabilized by bed rest and hydration without any other special treatment. Regarding the 5 cases of rectal bleeding, 1 patient was from group 1, 2 patients were from group 2, and 2 patients were from group 3. The bleeding in all cases was stopped within 30 minutes and no additional hospitalization or outpatient visits were required. Similarly, in the telephone interview conducted 3 days after biopsy, it was found that no additional pain or other complications had developed.

Go to :

With the prolongation of the average life span, the incidence of prostate cancer has rapidly increased worldwide in recent years. In 2005, in America, the number of patients who experienced prostate biopsy increased such that more than 770,000 cases of transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy were performed. Recent statistics indicate that, even if cancer is not detected at the initial biopsy, it is detected at rebiopsy in 21% to 29% cases [20-22], and thus the importance of rebiopsy has been emphasized. The greatest factor contributing to patients??refusal to undergo rebiopsy may be the pain felt at the time of the initial biopsy. Redelmeier et al reported that when colonoscopy is performed repeatedly on patients who have experienced colonoscopy once, their pain score is higher than that of patients undergoing colonoscopy for the first time [23]. Therefore, from the aspect of reducing the discomfort of patients, pain reduction is important and it is thought to play a role in the willingness to undergo rebiopsy if needed. In our study, not only the pain at the time of the prostate biopsy but also the willingness regarding rebiopsy were studied. In addition, similar to colonoscopy, pain scores may be increased due to previous experiences; thus, in our study, patients who experienced prostate biopsy in the past were excluded.

Transrectal ultrasonography was first applied to examine the prostate in 1963 by Takahashi and Ouchi [24]. In 1989, Hodge et al performed transrectal ultrasound-guided 6-core prostate biopsy [25]. Afterward, this method was used as the standard method for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. To raise the rate of diagnosis, the method has been modified to include an increased number of biopsy cores. Recently, efforts have been made to reduce the pain of patients, and bleeding, infection, and other complications caused by biopsy have been considered.

Although numerous studies on the methods used to reduce pain have been conducted in Korea as well as in other countries, to date, standard procedures have not been established. Currently, the most widely used method for pain reduction is the nerve block method using 1% lidocaine before biopsy [18]. Additional methods are the application of lidocaine gel to the rectum and the periprostate area [5-10], injection of diclofenac or ketorolac [11,12], midazolam administration [13], inhalation anesthesia using N2O [14,15], and intravenous anesthesia using propofol [16,17]. From the aspect of convenience and effectiveness, however, whether to consider these as standard procedures is controversial.

Irani et al have reported that the application of lidocaine gel to the rectum and the peri-prostate area was effective; however, a control group was not included in that study [1]. Desgrandchamps et al compared a group in which 2% lidocaine was applied to the rectum with a control group in which ultrasound gel was applied and reported that the application of lidocaine to the rectum did not improve the patients??pain at the time of biopsy [26]. In Korea, Song et al showed that the pain level of a group in whom lidocaine was applied to the rectum was not significantly different from that of a control group in whom saline was injected into the periprostatic area [27]. Although numerous studies have been performed on the application of lidocaine gel to the rectum and the periprostatic area, concurrent effects have not been reported [5-8,10]. The anesthetic effect of the injection of diclofenac or ketorolac alone is relatively insufficient, and thus cases without sufficient reduction of pain are frequently seen. Sedatives such as midazolam may induce severe side effects such as delirium, confusion, amnesia, and respiratory failure, and elderly males are more vulnerable to the development of these complications [28]. Because many people have an aversion to general anesthesia, inhalation anesthesia with N2O and intravenous anesthesia with propofol are difficult to perform in reality, and these methods are also cost-ineffective.

The purpose of this study was to assess the effect of the oral administration of 650 mg acetaminophen and EMLA cream in addition to intravenous injection of tramadol and to compare their effects with the conventional method used to reduce pain. The VAS, a method that is used in many fields to assess pain, was used for the comparison. The VAS can be used regardless of age, language, and race, and because it is numerically assessed, it is a good method for comparing pain statistically.

The results of our study showed that in comparison with the conventional periprostatic nerve block method, the pain-relieving effect of the oral administration of 650 mg acetaminophen and the application of EMLA cream was excellent, and no side effects induced by the drugs were detected. In particular, the advantage of the oral administration of 650 mg acetaminophen and the topical application of EMLA cream is that the pain caused by use of the needle for injection of the 1% lidocaine does not occur. When the periprostatic nerve block procedure is performed, the number of needle injections is increased in addition to conventional biopsy by more than two, which may be associated with complications such as prostatitis and bleeding. However, in our study, the complication rate of group 1, in which nerve block was performed, was not significantly different from that of groups 2 and 3, in which nerve block was not performed. These findings agree with the study reported by Obek et al [29].

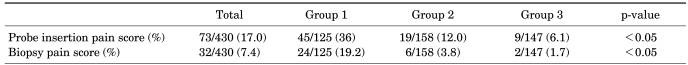

In the evaluation of VAS pain scores, scores of 1 to 3 are considered mild, 4 to 6 moderate, and ≥7 severe [30]. In this study, the average pain scores of the three groups showed mild to moderate pain scores. The ratios of the patients presenting with severe pain (≥7) at the time of probe insertion were 36% (group1), 12.0% (group 2), and 6.1% (group 3). The ratios at the time of biopsy were 19.2% (group 1), 3.8% (group 2), and 1.7% (group 3). The differences between the three groups were all significant (Table 4).

The anxiety and pain caused by prostate biopsy are associated with the anal pain induced by the ultrasonography probe insertion and the pain induced by the needles at the time of biopsy. However, the anal pain during probe insertion is known to cause more pain than the biopsy itself [26]. In our study, similarly, comparable results were observed, and in comparison with group 1, the anal pain that developed at the time of the insertion of the ultrasonography probe in groups 2 and 3 was statistically significantly reduced.

The advantages of our study were that the biopsies were performed by a single urologist, and thus our study is superior to other studies in which biopsies were performed by several urologists. In addition, the oral administration of acetaminophen before prostate biopsy or the use of EMLA cream are simple, side effects were rare, the pain that developed at the time the ultrasonography probes passed through the anus and the pain that developed at the time of biopsy could be reduced, and willingness to undergo rebiopsy was increased. Regarding selecting a preferable method, patients' kidney and liver functions as well as their perirectal skin condition should be taken under consideration, because acetaminophen can cause hepatitis or renal insufficiency, although very rarely, and EMLA should not be used with open wounds.

A potential imitation of our study is that the VAS is a very subjective index. The absence of a control group with tramadol is also a limitation, because tramadol may have achieved significant relief of pain.

Go to :

According to the results of our study, oral administration of 650 mg acetaminophen and topical application of EMLA cream, in addition of intravenous tramadol, reduce pain and are both technically easy, noninvasive, and safe. Moreover, these methods were more effective for pain relief than was the conventional periprostatic nerve block method. Therefore, they are thought to be useful methods of relieving pain during prostate biopsy.

Go to :

Notes

We acknowledge the financial support of the Healthy Medical Treatment Research and development Program of the Ministry of Health & Welfare (No. A090481).

Go to :

References

1. Irani J, Fournier F, Bon D, Gremmo E, Doré B, Aubert J. Patient tolerance of transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate. Br J Urol. 1997; 79:608–610. PMID: 9126093.

2. Collins GN, Lloyd SN, Hehir M, McKelvie GB. Multiple transrectal ultrasound-guided prostatic biopsies--true morbidity and patient acceptance. Br J Urol. 1993; 71:460–463. PMID: 8499991.

3. Crundwell MC, Cooke PW, Wallace DM. Patient's tolerance of transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy: an audit of 104 cases. BJU Int. 1999; 83:792–795. PMID: 10368198.

4. Alavi AS, Soloway MS, Vaidya A, Lynne CM, Gheiler EL. Local anesthesia for ultrasound guided prostate biopsy: a prospective randomized trial comparing 2 methods. J Urol. 2001; 166:1343–1345. PMID: 11547070.

5. Chang SS, Alberts G, Wells N, Smith JA Jr, Cookson MS. Intrarectal lidocaine during transrectal prostate biopsy: results of a prospective double-blind randomized trial. J Urol. 2001; 166:2178–2180. PMID: 11696730.

6. Cevik I, Ozveri H, Dillioglugil O, Akdaş A. Lack of effect of intrarectal lidocaine for pain control during transrectal prostate biopsy: a randomized prospective study. Eur Urol. 2002; 42:217–220. PMID: 12234505.

7. Kravchick S, Peled R, Ben-Dor D, Dorfman D, Kesari D, Cytron S. Comparison of different local anesthesia techniques during TRUS-guided biopsies: a prospective pilot study. Urology. 2005; 65:109–113. PMID: 15667874.

8. Mutaguchi K, Shinohara K, Matsubara A, Yasumoto H, Mita K, Usui T. Local anesthesia during 10 core biopsy of the prostate: comparison of 2 methods. J Urol. 2005; 173:742–745. PMID: 15711260.

9. Rodriguez A, Kyriakou G, Leray E, Lobel B, Guillé F. Prospective study comparing two methods of anaesthesia for prostate biopsies: apex periprostatic nerve block versus intrarectal lidocaine gel: review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2003; 44:195–200. PMID: 12875938.

10. Issa MM, Bux S, Chun T, Petros JA, Labadia AJ, Anastasia K, et al. A randomized prospective trial of intrarectal lidocaine for pain control during transrectal prostate biopsy: the Emory University experience. J Urol. 2000; 164:397–399. PMID: 10893594.

11. Haq A, Patel HR, Habib MR, Donaldson PJ, Parry JR. Diclofenac suppository analgesia for transrectal ultrasound guided biopsies of the prostate: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Urol. 2004; 171:1489–1491. PMID: 15017205.

12. Mireku-Boateng AO. Intravenous ketorolac significantly reduces the pain of office transrectal ultrasound and prostate biopsies. Urol Int. 2004; 73:123–124. PMID: 15331895.

13. Shrimali P, Bhandari Y, Kharbanda S, Patil M, Srinivas V, Gaitonde S, et al. Transrectal ultrasound-guided prostatic biopsy: midazolam, the ideal analgesic. Urol Int. 2009; 83:333–336. PMID: 19829036.

14. Masood J, Shah N, Lane T, Andrews H, Simpson P, Barua JM. Nitrous oxide (Entonox) inhalation and tolerance of transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy: a double-blind randomized controlled study. J Urol. 2002; 168:116–120. PMID: 12050503.

15. Manikandan R, Srirangam SJ, Brown SC, O'Reilly PH, Collins GN. Nitrous oxide vs periprostatic nerve block with 1% lidocaine during transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy of the prostate: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Urol. 2003; 170:1881–1883. PMID: 14532798.

16. Kitamura T, Fujiwara H, Nagata O, Usui H, Suzuki T, Ogawa M, et al. Anesthetic management using propofol and fentanyl for transrectal ultrasound-guided prostatic biopsy. Masui. 2001; 50:1209–1212. PMID: 11758325.

17. Cha KS, Lee SW, Cho JM, Kang JY, Yoo TK. Efficacy and safety of intravenous propofol anesthesia during transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. Korean J Urol. 2009; 50:757–761.

18. Pareek G, Armenakas NA, Fracchia JA. Periprostatic nerve blockade for transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy of the prostate: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Urol. 2001; 166:894–897. PMID: 11490241.

19. Raffa RB, Friderichs E, Reimann W, Shank RP, Codd EE, Vaught JL. Opioid and nonopioid components independently contribute to the mechanism of action of tramadol, an 'atypical' opioid analgesic. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992; 260:275–285. PMID: 1309873.

20. Singh H, Canto EI, Shariat SF, Kadmon D, Miles BJ, Wheeler TM, et al. Predictors of prostate cancer after initial negative systematic 12 core biopsy. J Urol. 2004; 171:1850–1854. PMID: 15076292.

21. Rabets JC, Jones JS, Patel A, Zippe CD. Prostate cancer detection with office based saturation biopsy in a repeat biopsy population. J Urol. 2004; 172:94–97. PMID: 15201745.

22. Djavan B, Remzi M, Schulman CC, Marberger M, Zlotta AR. Repeat prostate biopsy: who, how and when? A review. Eur Urol. 2002; 42:93–103. PMID: 12160578.

23. Redelmeier DA, Katz J, Kahneman D. Memories of colonoscopy: a randomized trial. Pain. 2003; 104:187–194. PMID: 12855328.

24. Takahashi H, Ouchi T. The ultrasonic diagnosis in the field of urology (the first report). Proc Jap Soc Ultrasonics Med. 1963; 3:7–10.

25. Hodge KK, McNeal JE, Terris MK, Stamey TA. Random systematic versus directed ultrasound guided transrectal core biopsies of the prostate. J Urol. 1989; 142:71–74. PMID: 2659827.

26. Desgrandchamps F, Meria P, Irani J, Desgrippes A, Teillac P, Le Duc A. The rectal administration of lidocaine gel and tolerance of transrectal ultrasonography-guided biopsy of the prostate: a prospective randomized placebo-controlled study. BJU Int. 1999; 83:1007–1009. PMID: 10368245.

27. Song S, Ji YH, Lee SB, You D, Kim JK, Park JY, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing effectiveness of local anesthesia techniques in patients undergoing transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. Korean J Urol. 2004; 45:236–239.

28. Greenblatt DJ, Abernethy DR, Locnskar A, Harmatz JS, Limjuco RA, Shader RI. Effect of age, gender, obesity on midazolam kinetics. Anesthesiology. 1984; 61:27–35. PMID: 6742481.

29. Obek C, Onal B, Ozkan B, Onder AU, Yalcin V, Solok V. Is periprostatic local anesthesia for transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy associated with increased infectious or hemorrhagic complications? A prospective randomized trial. J Urol. 2002; 168:558–561. PMID: 12131309.

30. Mallick S, Humbert M, Braud F, Fofana M, Blanchet P. Local anesthesia before transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy: comparison of 2 methods in a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2004; 171:730–733. PMID: 14713798.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download