Abstract

Purpose

Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedures are used for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women. The procedures with synthetic materials can have a risk of vaginal erosion. We experienced transobturator suburethral sling (TOT) tape-induced vaginal erosion and report the efficacy of a vaginal mucosal covering technique.

Materials and Methods

A total of 560 female patients diagnosed with stress urinary incontinence underwent TOT procedures at our hospital between January 2005 and August 2009. All patients succeeded in follow-ups, among which 8 patients (mean age: 50.5 years) presented with vaginal exposure of the mesh. A vaginal mucosal covering technique was performed under local anesthesia after administration of antibiotics and vaginal wound dressings for 3-4 days.

Results

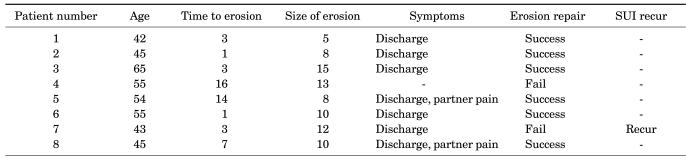

Seven of the 8 patients complained of persistent vaginal discharge postoperatively. Two of the 8 patients complained of dyspareunia of their male partners. The one remaining patient was otherwise asymptomatic, but mesh erosion was discovered at the routine follow-up visit. Six of the 8 patients showed complete mucosal covering of the mesh after the operation (mean follow-up period: 16 moths). Vaginal mucosal erosion recurred in 2 patients, and the mesh was then partially removed. One patient had recurrent stress urinary incontinence.

Go to :

Among the minimally invasive and simple surgical procedures for female stress urinary incontinence, tension-free vaginal tape (TVT), which was developed by Ulmsten et al in 1996, has been documented to be very effective [1]. However, approaching into the posterior pubic cavity may result in bladder perforation and injuries to vessels, nerves, and bowels. To minimize such complications, the tension-free transobturator suburethral sling (TOT) was developed [2]. During this procedure, the use of synthetic tape material (polypropylene monofilament mesh) can decrease the disadvantages of the conventional procedure using fascia graft such as tenderness and increased procedure time, but it may cause rejection, infection, and erosion [3]. Once such complications have occurred, the synthetic mesh must be removed, and the incidence of synthetic mesh-related erosion is reported to be 0.2-22% [4]. When the synthetic tape has been removed due to erosion, the patient becomes anxious about the recurrence of stress incontinence and the economic burden of reoperation [5,6]. Therefore, we performed a conservative surgical procedure by covering the eroded tape with the vaginal mucosa instead of removing it. Here we report the effectiveness of this conservative procedure.

Go to :

The study was conducted on 560 patients who were followed up for more than 3 months among those who had been diagnosed with stress urinary incontinence by urodynamic study and underwent the TOT operation by the same surgeon from January 2005 until August 2009 in our hospital. Outpatient observations were performed at 2 weeks, 1 month, and 3 months after the operation by observing the vaginal mucosa with the use of a speculum. Eight patients developed vaginal mucosal erosion (average age: 50.5 years) and underwent the vaginal mucosal covering technique.

Patients with tape-induced vaginal erosion were admitted and treated with intravenous antibiotics using secondgeneration cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, and metronidazole. In addition, we applied vaginal dressings using povidone iodine and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and performed irrigation with normal saline with the patient lying in the supine position 2-3 times a day. After 3-4 days of treatment, as the inflammatory findings of the erosion and vaginal mucosa disappeared, we applied local anesthesia on the mucosa surrounding the eroded tape with 2% lidocaine and designed a mucosal flap around the exposed mesh (Fig. 1). We checked for urethral erosion via cystoscope, removed granuloma around the tape, and performed undermining of the submucosal layer until there was no tension on the mucosal flap. After bleeding had been controlled completely by use of a Bovie cautery, we covered the tape with the vaginal wall mucosal advancement flap and sutured tightly with 4-0 chromic gut sutures (Fig. 2).

After the procedure, the patient underwent vaginal packing with Betadine-soaked Vaseline gauze that was removed the next morning. A dressing with povidone iodine and hydrogen peroxide was applied for 2-3 days. After the wound had become clean without pus or discharge, the Foley catheter was removed and the patient was discharged with oral antibiotics and Betadine vaginal suppositories for 2 weeks. At 2 weeks, 1 month, and 3 months after discharge, the patient was examined for any recurrence of mucosal erosion.

Go to :

None of the patients experienced complications during the operation and it took an average of 8 months (range, 1-16 months) until the vaginal mucosal erosion was found. There was no erosion on the urinary bladder or urethra. Seven patients complained of sustained vaginal discharge and 2 patients complained of dyspareunia of their partners. None of the patients suffered from systemic inflammation or surgical wound tenderness. The average size of the erosions was 10 mm (range, 5-15 mm), and after an average of 17 months (range, 6-40 months) of follow-up, 6 patients were successfully treated, whereas 2 patients experienced recurrence of vaginal erosion and underwent partial tape removal. Among the 2 patients who underwent tape removal, stress urinary incontinence recurred in 1 patient (Table 1).

Go to :

Among the surgical treatments for female stress urinary incontinence, TVT is widely used as a noninvasive technique based on the integral theory that the mid-urethra plays an important role in the continence mechanism [1]. Despite its high success rate, complications like bladder perforation, bowel perforation, hemorrhage, and nerve injury may occur [1,2]. To lessen such complications, an operation through the obturator foramen TOT was developed, which has become the most widely used technique. During TVT or TOT operations, synthetic tape is placed to reinforce the hammock in the mid-urethra. The incidence of vaginal erosion after the operation is reported to be 0.2-22% [4], which was 1.4% in our hospital. The exact mechanism for such tape erosions remains unknown, but possible explanations include subclinical wound infection, excessive sling tension, small mesh pore size, poor mesh incorporation, radiotherapy, postoperative vaginal atrophy, and premature sexual intercourse after operation [7,8]. The incidence of vaginal erosion was the same for both TOT and TVT, and to minimize the difference between operators we chose only patients who were operated on by the same surgeon. In addition, to control the difference among the synthetic materials, we used only type 1 (macroporous monofilament polypropylene) tape. The incidence of vaginal erosion with type 1 tape is reported to be around 0.2-1.2%, which is slightly lower than the incidence in our hospital, which is 1.4%. We expect the incidence to be reduced with increased numbers of cases, strict infection control, and more precise application of the surgical procedure.

The symptoms of vaginal mucosal erosion include sustained vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, dyspareunia of the patient or her partner, and recurrent urinary tract infection [8]. The patients in our hospital complained of sustained vaginal discharge (7 patients) and dyspareunia of their male partners (2 patients), and 1 patient was asymptomatic. Because there were patients who had been asymptomatic for 16 months and in whom vaginal erosion was diagnosed during screening for cervical cancer, careful vaginal examination is required for patients who have sustained vaginal discharge after operation. Once vaginal mucosal erosion has been found, the urethra and bladder must also be examined via cystoscope for possible erosion.

The recommended treatment for vaginal erosion is partial or complete removal of the tape, which should be decided upon according to the size of the erosion, symptoms of localized or systemic infection, and the type of tape. However, removal of the tape may result in recurrence of stress incontinence [4,7]. In our hospital, 1 of the 2 patients who underwent tape removal experienced recurrence of stress urinary incontinence.

Kobashi and Govier reported complete mucosal recovery after 6 weeks of prohibition of sexual intercourse without any antibiotics or hormone administration in 4 patients who had mucosal defects of less than 1 cm after receiving SPARC [9]. Al-Wadi et al treated a 43-year-old patient having a 1x2 cm sized vaginal erosion with intravaginal estrogen for 2 months. However, because conservative management failed, they covered the t-tape with a bulbocavernous fat pad graft [10]. Conservative treatment consumes much time and martius grafting has the disadvantage of leaving an incision wound on the labia majora. Domingo et al insisted that the tape must be completed removed because conservative treatment and observation has a poor outcome [11]. Lee et al conserved the tape and covered the mucosal defect with a randomized mucosal flap in 3 patients but failed in all 3 [12]. The presence of a foreign body as well as an inflammatory response on the tape increases the failure rate of the flap operation.

In our hospital, we did not remove the tape and to shorten the duration of treatment we concentrated on improving the inflammation through meticulous vaginal dressing (2-3 times per day) and the administration of triple antibiotics. As soon as the inflammation had regressed, we built a mucosal flap by using the mucosa below and above the defect (vertical to the tape) with sufficient thickness for better circulation. In addition, we reduced the possibility of vessel injury by forming the flap bilaterally and thereby achieved a higher success rate.

Go to :

References

1. Ulmsten U, Henriksson L, Johnson P, Varhos G. An ambulatory surgical procedure under local anesthesia for treatment of female urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1996; 7:81–85. PMID: 8798092.

2. Delorme E. Transobtuator urethral suspension: mini-invasive procedure in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women. Prog Urol. 2001; 11:1306–1313. PMID: 11859672.

3. Kim TH, Seo JT. Comparison of the efficacy and vaginal erosion rate between monofilament and multifilament polypropylene tapes for treating urinary incontinence. Korean J Urol. 2008; 49:844–849.

4. Karram MM, Segal JL, Vassallo BJ, Kleeman SD. Complications and untoward effects of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure. Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 101:929–932. PMID: 12738152.

5. Bafghi A, Benizri EI, Trastour CT, Benizri EJ, Michiels JF, Bongain A. Multifilament polypropylene mesh for urinary incontinence: 10 cases of infections requiring removal of the sling. BJOG. 2004; 112:376–378. PMID: 15713159.

6. Domingo S, Alama P, Ruiz N, Perales A, Pellicer A. Diagnosis, management and prognosis of vaginal erosion after transobturator suburethral tape procedure using a nonwoven thermally bonded polypropylene mesh. J Urol. 2005; 173:1627–1630. PMID: 15821518.

7. Bhargava S, Chapple CR. Rising awareness of the complications of synthetic slings. Curr Opin Urol. 2004; 14:317–321. PMID: 15626872.

8. Deval B, Haab F. Management of the complications of the synthetic slings. Curr Opin Urol. 2006; 16:240–243. PMID: 16770121.

9. Kobashi KC, Govier FE. Management of vaginal erosion of polypropylene mesh slings. J Urol. 2003; 169:2242–2243. PMID: 12771759.

10. Al-Wadi K, Al-Badr A. Martius graft for the management of tension-free vaginal tape vaginal erosion. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114:489–491. PMID: 19622973.

11. Domingo S, Alama P, Ruiz N, Perales A, Pellicer A. Diagnosis, management and prognosis of vaginal erosion after transobturator suburethral tape procedure using a nonwoven thermally bonded polypropylene mesh. J Urol. 2005; 173:1627–1630. PMID: 15821518.

12. Lee T, Kim JS, Jung JK, Lee HJ. Surgical management of vaginal wound healing defects after tension-free vaginal tape placement. Int J Urol. 2005; 12:699–701. PMID: 16045568.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download