Abstract

Purpose

This study was conducted to examine whether simultaneous transrectal prostate needle biopsy (TPNB) owing to an increase in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels is safe and effective in patients who are scheduled for transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Materials and Methods

Combined TPNB and TURP was performed in a total of 42 patients aged 60 years and older who had gray-zone PSA values (4-10 ng/ml) and PSA density (PSAD) values of 0.12 and less. The frequencies of fever, sepsis, and epididymitis were assessed after surgery. The diagnostic accuracy was assessed, and the results of histologic examination were evaluated in terms of TPNB or TURP. In addition, the diagnostic accuracy was assessed according to age.

Results

Prostate cancer was diagnosed in 6 (14.3%) of the 42 patients: 2 patients were diagnosed with prostate cancer by TPNB only, 3 patients by TURP only, and 1 patient by combined TPNB and TURP. Four (25%) of the 16 patients aged under 70 years and 2 (7.8%) of the 26 patients aged 70 years and older were diagnosed with prostate cancer. Fever was observed in 9 patients (21.4%), 4 (9.5%) of whom had a fever of higher than 38℃. The fever normalized the day after surgery in all 9 patients. No septicemia was noted. There were no serious complications related to combined TPNB and TURP.

Go to :

Prostate biopsy has been widely performed in clinical practice in patients with high prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, and the incidence of prostate cancer has increased. Although a serum PSA level of 3.0 or 4.0 ng/ml is used as a cutoff value for screening for prostate cancer, it is relatively difficult to discriminate prostate cancer from benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) in men with gray-zone PSA values (4-10 ng/ml) [1,2]. To increase the diagnostic accuracy of prostate biopsy, various parameters including PSA velocity [3], percent free PSA [4], age reference PSA ranges [5], and PSA density (PSAD) [6] have been used in clinical practice. PSAD values of ≥0.15 are generally regarded as being highly suspicious of prostate cancer [7].

With developments in prostate ultrasound and biopsy instruments, prostate biopsy can be performed under local anesthesia on an outpatient basis in most cases. The development of prostate biopsy techniques has reduced patient discomfort, but a considerable number of patients still complain of pain or discomfort [8]. Some patients refuse to undergo prostate biopsy because they recall the pain of previous biopsy procedures [9]. To reduce this discomfort, prostate biopsy is sometimes performed under general anesthesia or spinal anesthesia, which is often costly and time consuming. In cases in which the PSA level is within the gray zone, but the PSAD value is low, this increased PSA level is mostly attributed to BPH, suggesting a lower possibility of prostate cancer [10]. If combined prostate biopsy and transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is safe, the pain or discomfort experienced when prostate biopsy is performed separately can be avoided.

This study was conducted to examine whether simultaneous transrectal prostate needle biopsy (TPNB) is safe and effective in patients who are scheduled for TURP because of an increase in PSA levels.

Go to :

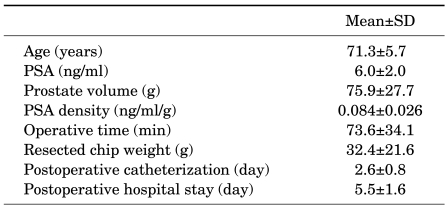

This study included a total of 42 patients aged ≥60 years who had PSA levels of 4 to 10 ng/ml and PSAD values of ≤0.12 and who underwent combined TPNB and TURP at our hospital. The mean age, prostate volume, PSA level, and PSAD value of the patients were 71.3±5.7 years, 75.9±27.7 g, 6.0±2.0 ng/ml, and 0.084±0.026, respectively (Table 1). PSA was measured by using the Tandem-R assay. Prostate volume was calculated by using the following formula:

π/6×L×W×H

where L=length, W=width, and H=height. PSAD was calculated by dividing PSA by prostate volume.

After prostate biopsy was performed with the patient under spinal anesthesia, the patient's position was changed into the lithotomy position for TURP. Prostate biopsy was conducted under transrectal ultrasound guidance by using the 8 core method before February 2008 and the 12 core method after March 2008. After surgery, the degree and duration of fever, the absence or presence of sepsis, and the development of complications, such as epididymitis or orchitis, were assessed. Fever was defined when the highest measurement was ≥37.5℃. The diagnostic accuracy was determined, and the results of histological examinations were evaluated according to TPNB alone or combined TPNB and TURP. The Gleason score was measured in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of prostate cancer (PCa group). Clinical characteristics, prostate volume, PSA, and PSAD were analyzed in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of BPH (BPH group) and in the PCa group. Diagnostic accuracy was analyzed in two groups of patients according to age: those <70 years and those ≥70 years.

All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA). Comparisons of clinical characteristics and parameters were made by using the Mann-Whitney test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Go to :

The mean volume of the resected specimen after TURP was 32.4±21.6 g. The durations of urethral catheter placement and admission were 2.6±0.8 and 5.5±1.6 days, respectively (Table 1). Of the total 42 patients, fever was noted in 9 patients (21.4%), 4 (9.5%) of whom had a fever of ≥38℃. All of the 9 patients had fever the day after surgery, and the fever subsided within 24 hours. No patients had sepsis, persistent hematospermia, orchitis, or epididymitis. There was no significant difference in the duration of hospital stay between the patients with fever and those without.

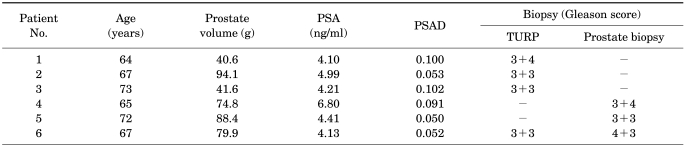

Of the total 42 patients, 6 (14.3%) were definitively diagnosed as having prostate cancer. Prostate cancer was diagnosed in 2 patients by TPNB alone, in 3 patients by TURP alone, and in 1 patient by both procedures. The Gleason score was 6 points in 3 patients and 7 points in 3 patients (Table 2).

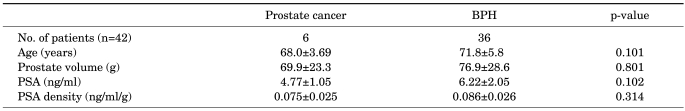

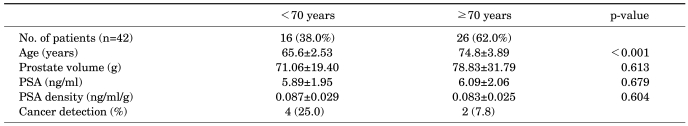

The PSA level was 4.77 ng/ml in the PCa group and 6.22 ng/ml in the BPH group, but the difference was not statistically significant. The PSAD value was 0.075 in the PCa group and 0.086 in the BPH group, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 3). According to the reference age of 70 years, there were no significant differences in prostate volume, the PSA level, or the PSAD value between the two age groups of <70 years and ≥70 years. The diagnostic accuracy was 25.0% (4/16) in the patients aged <70 years and 7.8% (2/26) in the patients aged ≥70 years (Table 4).

Go to :

With advancements in PSA screening tests, transrectal ultrasound, and biopsy instruments, prostate biopsy is widely performed in clinical practice. Although complications after prostate biopsy are not serious, many patients hesitate to undergo prostate biopsy because of pain or discomfort. Zisman et al reported that about 96% and 89% of patients undergoing prostate biopsy complained of pain and discomfort, respectively [8]. Many attempts to reduce pain during prostate biopsy have been made. Among them, infusion of lidocaine jelly is simple to use but its effect is controversial [11]. A previous study documented that about 82% of patients reported "No" to the question "Will you undergo prostate biopsy again if needed?" [12]. When prostate biopsy is performed under general anesthesia to avoid such discomfort or pain, the procedure costs are increased, although patient discomfort or pain can be reduced. Such problems can be solved if combined TPNB and TURP are performed in patients who need prostate biopsy although there is a low possibility of prostate cancer based on a PSA level within the gray zone but a low PSAD value. Shen et al reported that combined TPNB and TURP is safe without notable complications other than fever, which agrees with our results [13]. Of the total 42 patients in the present study, 9 (21.4%) had fever after surgery, 4 (9.5%) of whom had a fever of ≥38℃. Fever subsided in all 9 patients within 24 hours. There were no significant differences in the durations of urethral catheter placement and hospital stay between the patients with fever and those without fever. It has been reported that fever occurs in 4.4% or 6.2% of patients after TPNB alone [14,15]. In our study, a fever of ≥38℃ occurred in 9.5% of the patients without any significant difference between TPNB alone and combined TPNB and TURP. Palisaar et al indicated that open radical retropubic prostatectomy after TURP gives favorable surgical and functional outcomes without an increase in the incidence of complications or sexual dysfunction [16]. In our study, open radical retropubic prostatectomy was performed on 5 of the 6 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of prostate cancer, and there was no increase in the incidence of complications.

PSAD is used to increase diagnostic accuracy in patients who have gray-zone PSA values (4-10 ng/ml). Some investigators have proposed that prostate biopsy is indicated for patients with a PSAD value of ≥0.15, and others have advocated that the criteria should be lowered. Gohji et al reported that in a study of 287 patients with a PSA level of 2.1-10.0 ng/ml, the PSA level had a sensitivity of 90%, a specificity of 36%, and a positive predictive value of 14% in those with a PSAD value of <0.12 [17]. A recent study showed that in patients with a PSA level of 4-10 ng/ml, the PSA level had a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 33.7% at a PSAD cutoff value of 0.134 [18]. In our study, combined TPNB and TURP was performed on patients with a PSA level of 4-10 ng/ml as well as a PSAD value of <0.12. As a result, 6 patients (14.6%) were definitively diagnosed with prostate cancer. Prostate cancer was diagnosed in 2 patients (4.9) by TPNB alone, 3 patients (7.3%) by TURP alone, and 1 patient (2.4%) by combined TPNB and TURP. This result suggests that the diagnostic accuracy of TPNB alone is 7.3% in patients with a PSAD value of <0.12. It is generally recognized that TURP is effective in diagnosing prostate cancer in patients with negative TPNB results [19,20]. Of the 6 patients diagnosed with prostate cancer, prostate cancer was definitively diagnosed by TURP in 4 patients, 3 of whom were diagnosed by TURP alone. In other words, if TPNB alone had been performed on the aforementioned 3 patients, the results might have been negative and the patients might have needed to undergo repeated TPNB or TURP. We were able to reduce the frequency of TPNB by combined TPNB and TURP. On the basis of these findings, we can infer that combined TPNB and TURP may be more effective than repeated TPNB in the diagnosis of prostate cancer in patients with previous TPNB-negative results.

PSA tends to increase with age. The normal range of PSA has been reported to be 2.4-3.5 ng/ml in the 50 to 59 year group, 3.6-5.4 ng/ml in the 60 to 69 year group, and 5.2-7.5 ng/ml in the 70 to 79 year group [21-24]. Therefore, it is estimated that in elderly patients, the diagnostic accuracy of the PSA level may decrease in patients with low PSAD values. Meshref et al reported that the diagnostic accuracy of the PSA level in patients with a PSA level of 4.1-10 ng/ml was 0% in the 50 to 59 year group, 4.1% in the 60 to 69 year group, and 0% in the 70 to 79 year group at a PSAD cutoff value of 0.15 or less [25]. They also reported that the diagnostic accuracies of the PSA level were 4.2%, 1.5%, and 0%, respectively after adjustment for age (3.6-10 ng/ml for the 50 to 59 year group, 4.6-10 ng/ml for the 60 to 69 year group, and 6.6-10 ng/ml for the 70 to 79 year group). Those authors concluded that the diagnostic accuracy of the PSA level was 0% at a PSAD cutoff value of 0.15 or less in the ≥70 years age group. Kobayashi et al showed that diagnostic accuracy is low in patients aged ≥70 years with large prostate volumes [10]. Thus, because the increased PSA level is probably due to BPH in the ≥70 years age group, prostate biopsy should be avoided in patients aged ≥70 years with large prostate volumes. Similarly, we found that the diagnostic accuracy of the PSA level was 25% and 8%, respectively, for the age groups of <70 and ≥70 years. Because there is a high possibility of the presence of diabetes mellitus or use of anticoagulant medications, the incidence of complications after TPNB may be high. In BPH patients aged ≥70 years who are scheduled for TURP because they have a PSA level within the gray zone, separate TPNB can be avoided by performing combined TPNB and TURP.

Our study had some limitations. First, it was retrospective in nature and the number of subjects was relatively small. Second, even though TURP can enhance the diagnostic yield of prostate cancer in this group of patients, at the same time it could miss some chances of radical prostatectomy without prior TURP. However, we confirmed that combined TPNB and TURP is safe and that the possibility of prostate cancer may be reduced in elderly patients as found in previous studies.

Go to :

Because combined TPNB and TURP is a safe procedure, it should be performed on patients who need the 2 procedures. In particular, this combined procedure may be useful for patients with TPNB-negative results who need TURP. Moreover, because there is a low possibility of prostate cancer in BPH patients with a PSAD value of <0.12 and aged more than 70 years old, combined TPNB and TURP can prevent unnecessary TPNB before TURP.

Go to :

References

1. Catalona WJ, Richie JP, Ahmann FR, Hudson MA, Scardino PT, Flanigan RC, et al. Comparison of digital rectal examination and serum prostate specific antigen in the early detection of prostate cancer: results of a multicenter clinical trial of 6,630 men. J Urol. 1994; 151:1283–1290. PMID: 7512659.

2. Park HK, Hong SK, Byun SS, Lee SE. Comparison of the rate of detecting prostate cancer and the pathologic characteristics of the patients with a serum PSA level in the range of 3.0 to 4.0 ng/ml and the patients with a serum PSA level in the range 4.1 to 10.0 ng/ml. Korean J Urol. 2006; 47:358–361.

3. Lee SC, Lee SC, Kim WJ. Value of PSA density, PSA velocity and percent free PSA for detection of prostate cancer in patients with serum PSA 4-10 ng/ml patients. Korean J Urol. 2004; 45:747–752.

4. Lee SJ, Seo IY, Kim JS, Rim JS. The effectiveness of free/total prostate specific antigen (PSA) ratio for increasing the detection rate of prostate cancer in patients with serum PSA level 4-10ng/ml. Korean J Urol. 2001; 42:815–820.

5. Lee TK, Chung TG, Kim CS. Age-specific reference ranges of prostate specific antigen from a health center in Korea. Korean J Urol. 1999; 40:583–588.

6. Kim BK, Chang SH, Kim CI. Clinical significance of prostate-specific antigen density in patients with serum prostate specific antigen between 4 and 10 ng/ml. Korean J Urol. 2006; 47:1161–1165.

7. Rommel FM, Agusta VE, Breslin JA, Huffnagle HW, Pohl CE, Sieber PR, et al. The use of prostate specific antigen and prostate specific antigen density in the diagnosis of prostate cancer in a community based urology practice. J Urol. 1994; 151:88–93. PMID: 7504748.

8. Zisman A, Leibovici D, Kleinmann J, Siegel YI, Lindner A. The impact of prostate biopsy on patient well-being: a prospective study of pain, anxiety and erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2001; 165:445–454. PMID: 11176394.

9. Jones JS, Ulchaker JC, Nelson D, Kursh ED, Kitay R, Angie S, et al. Periprostatic local anesthesia eliminates pain of office-based transrectal prostate biopsy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2003; 6:53–55. PMID: 12664066.

10. Kobayashi T, Mitsumori K, Kawahara T, Nishizawa K, Ogura K, Ide Y. Prostate gland volume is a strong predictor of biopsy results in men 70 years or older with prostate-specific antigen levels of 2.0-10.0 ng/mL. Int J Urol. 2005; 12:969–975. PMID: 16351653.

11. Autorino R, De Sio M, Di Lorenzo G, Damiano R, Perdona S, Cindolo L, et al. How to decrease pain during transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy: a look at the literature. J Urol. 2005; 174:2091–2097. PMID: 16280735.

12. Cha KS, Lee SW, Cho JM, Kang JY, Yoo TK. Efficacy and safety of intravenous propofol anesthesia during transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. Korean J Urol. 2009; 50:757–761.

13. Shen BY, Chang PL, Lee SH, Chen CL, Tsui KH. Complications following combined transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate needle biopsies and transurethral resection of the prostate. Arch Androl. 2006; 52:123–127. PMID: 16443589.

14. Gustafsson O, Norming U, Nyman CR, Ohström M. Complications following combined transrectal aspiration and core biopsy of the prostate. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1990; 24:249–251. PMID: 2274747.

15. Rietbergen JB, Kruger AE, Kranse R, Schröder FH. Complications of transrectal ultrasound-guided systematic sextant biopsies of the prostate: evaluation of complication rates and risk factors within a population-based screening program. Urology. 1997; 49:875–880. PMID: 9187694.

16. Palisaar JR, Wenske S, Sommerer F, Hinkel A, Noldus J. Open radical retropubic prostatectomy gives favourable surgical and functional outcomes after transurethral resection of the prostate. BJU Int. 2009; 104:611–615. PMID: 19298408.

17. Gohji K, Nomi M, Egawa S, Morisue K, Takenaka A, Okamoto M, et al. Detection of prostate carcinoma using prostate specific antigen, its density, and the density of the transition zone in Japanese men with intermediate serum prostate specific antigen concentrations. Cancer. 1997; 79:1969–1976. PMID: 9149025.

18. Zheng XY, Xie LP, Wang YY, Ding W, Yang K, Shen HF, et al. The use of prostate specific antigen (PSA) density in detecting prostate cancer in Chinese men with PSA levels of 4-10 ng/ml. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008; 134:1207–1210. PMID: 18446367.

19. Puppo P, Introini C, Calvi P, Naselli A. Role of transurethral resection of the prostate and biopsy of the peripheral zone in the same session after repeated negative biopsies in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2006; 49:873–878. PMID: 16439052.

20. Cho KJ, Ha US, Lee CB. Role of transurethral resection of the prostate in the diagnosis of prostate cancer for patients with lower urinary tract symptoms and serum PSA 4-10 ng/ml with a negative repeat transrectal needle biopsy of prostate. Korean J Urol. 2007; 48:1010–1015.

21. Oesterling JE, Cooner WH, Jacobsen SJ, Guess HA, Lieber MM. Influence of patient age on the serum PSA concentration. An important clinical observation. Urol Clin North Am. 1993; 20:671–680. PMID: 7505975.

22. Dalkin BL, Ahmann FR, Kopp JB. Prostate specific antigen levels in men older than 50 years without clinical evidence of prostatic carcinoma. J Urol. 1993; 150:1837–1839. PMID: 7693980.

23. Anderson JR, Strickland D, Corbin D, Byrnes JA, Zweiback E. Age-specific reference ranges for serum prostate-specific antigen. Urology. 1995; 46:54–57. PMID: 7541586.

24. Choi YD, Kang DR, Nam CM, Kim YS, Cho SY, Kim SJ, et al. Age-specific prostate-specific antigen reference ranges in Korean men. Urology. 2007; 70:1113–1116. PMID: 18158029.

25. Meshref AW, Bazinet M, Trudel C, Aronson S, Peloquin F, Nachabe M, et al. Role of prostate-specific antigen density after applying age-specific prostate-specific antigen reference ranges. Urology. 1995; 45:972–979. PMID: 7539562.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download