Abstract

Purpose

Uroflowmetry (UFM) requires at least 125ml to 150ml of urine volume for an adequate interpretation. It is common to repeat UFM in clinical settings because of an insufficient voided volume, which may be induced by increased anxiety. To reduce performing repeated UFMs, we evaluate the usefulness of performing a prevoiding sonographic bladder scan and we determined the anxiety level before performing UFM.

Materials and Methods

We enrolled one hundred two patients (mean age: 62.6±15.0 years) who visited our clinic due to voiding dysfunction. The bladder volume prior to UFM was measured by an automated bladder scan (Biocon-500™, Mcube Technology) when the patients felt a strong fullness sensation. All the patients kept a voiding diary for 3 days, and they underwent the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory questionnaire, the fullness scale and UFM.

Results

The mean prevoiding volume was 307±124ml and the mean voided volume was 271±129ml. There was a correlation between the prevoiding scan volume and the voided volume: voided volume=17.502+ (0.724xprevoiding volume) (r=0.851, p<0.001). Among the 333 patients without a bladder scan and who had UFM performed, 25.8% showed insufficient voided volumes of less than 125ml, and 32.4% showed voided volumes of less than 150ml. However, among the 102 patients who underwent a bladder scan, 9.8% showed insufficient voided volumes of less than 125ml and 12.7% showed voided volumes of less than 150ml (p<0.001). The patients who had a higher state of anxiety than trait anxiety before their UFM revealed a relatively decreased functional bladder capacity (p=0.013).

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

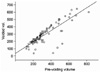

Linear regression analysis, calculated as voided volume= 17.502+(0.724xpre-voiding volume) (r=0.851, p<0.001).

References

1. Benign prostatic hyperplasia guideline panel. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: diagnosis and treatment. Clinical practice guideline 8. 1994. Rockville: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research;42–46.

2. Chung B, Lee T, Yang JH. The diagnostic value of portable bladder volume measurement system (BVMS) with real bladder image in the measurement of bladder volume according to the different angling of transducer. 34th International Continence Society. 2004. Paris: 740.

3. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RC, Lushene RE. Mannual for the State-Trait anxiety inventory. 1983. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press;12.

4. Helvaci MR, Seyhanli M. What a high prevalence of white coat hypertension in society! Intern Med. 2006. 45:671–674.

5. Jensen KM. Uroflowmetry in elderly men. World J Urol. 1995. 13:21–23.

6. Tong YC. The effect of psychological motivation on volumes voided during uroflowmetry in healthy aged male volunteers. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006. 25:8–12.

7. Boci R, Fall M, Walden M, Knutson T, Dahlstrand C. Home uroflowmetry: improved accuracy in outflow assessment. Neurourol Urodyn. 1999. 18:25–32.

8. Reynard JM, Peters TJ, Lim C, Abrams P. The value of multiple free-flow studies in men with lower urinary tract symptoms. Br J Urol. 1996. 77:813–818.

9. Pagani M, Rimoldi O, Pizzineli P, Furlan R, Crivellaro W, Liberati D, et al. Assessment of the neural control of the circulation during psychological stress. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1991. 35:33–41.

10. McNaughton-Collins M, Barry MJ. Managing patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Med. 2005. 118:1331–1339.

11. Reynard JM, Yang Q, Donovan JL, Peters TJ, Schaffer W, de la Rosette JJ, et al. The ICS-'BPH' study: uroflowmetry, lower urinary tract symptoms and bladder outlet obstruction. Br J Urol. 1998. 82:619–623.

12. Erdem E, Akbay E, Doruk E, Cayan S, Acar D, Ulusoy E. How reliable are bladder perceptions during cystometry? Neurourol Urodyn. 2004. 23:306–309.

13. Dicuio M, Creti S, Di Campli A, Dipietro R, Mannini D, Nanni G, et al. Usefulness of a prevoiding transabdominal sonographic bladder scan for uroflowmetry in patients involved in clinical studies of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Ultrasound Med. 2003. 22:773–776.

14. Patel HR, Garcia-Montes F, Christopher N, Reeves BC, Emberton M. Diagnostic accuracy of flow rate testing in urology. BJU Int. 2003. 92:58–63.

15. Reynard JM, Lim C, Abrams P. Significance of intermittency in men with lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology. 1996. 47:491–496.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download