Abstract

Deaths of suspects or inmates while in custody and incarceration is a tragedy for families and could become a public issue. Such deaths occur within a complicated brew of ethical and legal hurdles that must be handled with caution. We conducted a survey about these deaths. We collected and reviewed 85 cases of death that occurred while in custody and incarceration in Seoul and the Gyeonggi province, including e postmortem examinations between 2004 and 2011. Natural causes (most commonly cardiovascular diseases) accounted for nearly half of the deaths in custody, and unnatural causes accounted for nearly all of the remainder. Suicidal strangulation (hanging and self-strangulation) was the most common cause, followed by poisoning. Natural deaths by cardiovascular disease and unnatural deaths by suicidal strangulations, poisoning accounted for most cases of death while in custody and during incarceration. We hope this study can facilitate policy proposals to address this problem, helping authorities to reduce the occurrences of these preventable and untimely deaths of individuals in custody and incarceration.

The deaths while under police custody or prison may attract public interests or attentions that need to be handled carefully with scrutiny.1) Whenever such deaths occur in custody or during incarceration, controversial and legal issues or litigation may occur and a postmortem examination with meticulous investigation needs to be done. These deaths lie in a very complicated brew of ethical, legal and medical hurdles involving several authorities which can be hard to handle. In the past, some deaths became important public issues,2, 3) and some of these deaths have contributed to the total incidences of suicide.4, 5) Therefore, we conducted this study to examine these deaths so that we, forensic pathologists, may know how to handle sensitive issues regarding these types of deaths and we can make recommendations for policy to reduce more incidences of these deaths.

All our cases analyzed in this study occurred while in custody and incarceration, under police or prosecutor's investigation and judicial process. Custody not only includes detention in lockup or a holding cell at police station or the prosecutor's office, but also all procedures from first encounter to arrest or release. Incarceration covers local jails and prisons. We collected all cases in which the deaths in custody or incarceration occurred in Seoul and Gyeonggi province, consulted the postmortem examination from 2004 to 2011. We reviewed all autopsy reports including autopsy findings, toxicological tests, medical records, reports from the police officers' investigation.

In police custodies and incarcerations between 2004 and 2011, we found a total of 85 cases, consisting of 81 local residents and 4 foreigners. The majority of the deceased were overwhelmingly male (97.6%, 83) and their age varied between 20 and 73 years old with the average age of 46 years. The 4 foreigners were two Chinese, a Vietnamese, and an American.

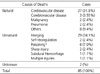

42 cases (49.4%) died of natural causes. Cardiovascular disease was the most common cause, followed by cerebrovascular disease, malignancy, pneumonia and others. Only 10 cases had a medical history; diabetes mellitus, hypertension, depression, asthma, epilepsy, unstable angina, meningitis, cerebral infarction, oropharyngeal cancer, and leukemia. The majority of these histories were not directly related to the cause of death. 4 cases (4.7%) occurred in custody and 38 cases (44.7%) in incarceration in local jail or prisons (Tables 1 and 2).

41 cases (48.2%) died of unnatural causes. Hanging was the most common cause (34.1%, 29), followed by herbicide (paraquat) and cyanide poisoning (7.0%, 6). 2 cases died by self-strangulation, 2 cases by self-injury (fatal sharp injury of the neck or abdomen), 1 case by multiple injuries from a fall from height, and 1 case by acute subdural hemorrhage. In 1 of 2 sharp injury cases, the deceased was found with a fatal abdominal stab injury immediately after he was falling down from a Taser gun. Most cases (38.8%, 32) occurred during incarceration, 7 cases (8.2%) in police custody, and 2 cases (2.4%) in the custody of the prosecutor's office. In 4 cases, the toxicological test showed positive results for a few drugs (antidepressants, antianxiety drugs, antipsychotics and others) but the level of drug in blood ranged within or below the therapeutic level. In another 5 cases (4 cases in police custody, 1 case occurred immediately after entering incarceration), they were under the influence of alcohol (between 0.14% and 0.269%) (Tables 1 and 2).

In 2 cases, the cause of death was unknown; in 1 case, the deceased was a foreigner (American) showing violent psychotic symptoms suddenly while in police custody. He was transported to a hospital but died shortly. There were no specific findings in the postmortem examination except for his urine testing positive for marijuana in the toxicological test. In the other case occurred during incarceration, there were also no specific findings in the postmortem examination.

Deaths which occur in police custody and incarceration cause great sadness to the family and loss of trust in the government. Although they committed a felony or misdemeanor that had to be processed by judicial procedure, it's the responsibility of legal system to protect their civil rights.6) Therefore we examined these deaths to recommend change of policy in order to prevent future occurrences. To the best of our knowledge, our study represents the first survey of deaths in custody and incarceration in Korea.

Natural deaths occupied nearly half of all cases. Most individuals died of cardiovascular diseases. During incarceration, all past medical history had to be reviewed and physicians regularly check their health in order to determine whether they are fit for imprisonment or if they need to be placed under special medical care. In cases where all medical histories were known, they received the necessary treatment or were transported to a hospital for further evaluation. Nevertheless, the majority didn't have any past histories and showed no specific symptoms or signs before their death and it was impossible to anticipate their death. Some of the deaths were unavoidable because they were caused by preexisting medical condition. As was the case of natural death with deep neck infection, (for which he received regular treatment by a volunteer dental service), unfortunately it was too late for treatment or were delayed getting appropriate medical care because of the limited medical service. Therefore, the guards who first meet, and often examine them, have to be educated to recognize early signs that signal the need for urgent medical care.7) And the authorities should consider how to provide a higher quality medical service including competent medical or professional staffs, an efficient healthcare system so on.

For deaths before incarceration, we assumed that there must be a loophole in the custody procedure; somewhere between first encountering a suspect or a citizen, during investigation, transporting to a local jail or prison, or during the process for entering incarceration. Because there was no time to check or examine their health, problems were discovered late, and the appropriate treatment was delayed. In many cases, during the procedure, there were no doctors or professional medical staff to handle any emergencies. In case of emergency, they had to call paramedics that would lead to get treatment. Considering that most individuals were in their 40s to 60s, police officers should be minded of their health and frequently check their condition. The authorities need to establish more rapid and efficient medical care system for them.

For unnatural causes of death, suicidal strangulation was most common and most of them occurred during incarceration but rarely in the prosecutor's office or police custody. The types of strangulation in our cases were hanging and in rare instances, self-strangulation. The cords used in strangulations were made with undershirts, blankets, uniform shirts, pants, or shoelaces, and in a few cases, rubber gloves, the elastic band of underwear, or plastic bags. They usually fastened the cords on the security grilles of windows at the restroom or living room and sometimes on a fan or a shelf on the wall. The most common times/periods to commit suicide were when security was light, usually early in the morning, late at night, while alone, or immediately after entering incarceration. No doubt it would be impossible for all guards to be vigilant at all times. However, during these times, it is necessary to heighten vigilance. According to the study about suicide in New South Wales prison, which shows a similar rate of occurrence, representing 41% of all deaths in custody, reinforced surveillance in the first week of incarceration can be an effective method of intervention.8) For their clothes or beddings, special designs that make it difficult to be torn should be considered and in the furnishings or the building structures, it is necessary to take preventive measures for risks in whatever situation they would encounter, including removal of potential risky objects.7)

Herbicide (paraquat) and cyanide poisoning occurred in custody and immediately after entering incarceration. The deceased suddenly disappeared during investigation at the police station or the prosecutor's office and they were later found dead having ingested drugs or chemicals, hanging themselves, or falling from a height. In one case, a police officer missed a concealed box cutter despite searching the person. As soon as he entered lockup, he injured himself cutting his neck. Therefore, police officers should search carefully for a concealed weapon, any toxic drugs, or chemicals before processing. And a least while they are under police custody, police officers need to be aware of their whereabouts. In a lockup, a restroom, or any place in the police office, it is also necessary to take prevented measures to all risks. In Australia, 339 recommendations in the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in custody (1991) final report were made for developing programs for prevention of suicide in custody and incarceration.9) These recommendations would be helpful for the improvement of our correction system.

In one case, the deceased died of a sharp abdominal injury related to the use of a TASER® gun.10) In order to stop him from injuring himself, the man was tasered and he fell immediately afterwards. As he fell, he received a severe stab injury in his abdomen from the blade he was holding. Obviously, such police action must be done for precluding of his suicide attempt and wild behavior, and he died of fatal stab injuries in his abdomen. Nevertheless, considering the physiological mechanism of Taser gun, it is very difficult to prove that police action might not contribute to his death. In our study, we had only one case involving the use of a Taser gun. But the use of a Taser gun are increasing in law enforcement agencies worldwide10-12) and its uses seems to be related to custody sudden deaths.11) Therefore, police officers should be trained on all available information on the use of a Taser gun, including the dangers.

It is difficult to compare our results to those of other countries because each country has their own jurisdiction system. But we found a similar survey conducting in another country and compared it with our own. The study performed in Ontario in Canada5) showed that for natural deaths, the occurrence rate (41%) was very similar to our results, and the common cause of death was cardiovascular disease, followed by cancer. And for violent deaths, suicide by strangulation was most common, followed by poisoning and homicide. Both studies showed similar results for the distribution of sex and age, in that males were overwhelmingly dominant and the mean age was in the 40s. Interestingly, in our study we didn't have any homicide cases but that it is most likely related to the limitation of our study. Our study covers only Seoul and Gyeonggi province, which includes 5 local jails and 4 prisons. The prisons for criminals who committed assaults, murders, or any other major crimes were not included in our study. This factor might contribute to or influence the reason why we had no homicide cases. Also in our study, herbicide (paraquat) and cyanide were used for the fatal suicides, in contrast to the study in Canada in which most cases were accidents due to drug overdose. In whatever the situations, police officers or guards need to be vigilant to the risks of drug overdose or intoxication and search for concealed chemicals.

The results of both our study and the study in Ontario described that suicide by strangulation and natural deaths caused by cardiovascular diseases were most common, implying that authorities should mainly focus on developing policy to reduce the occurrences of these preventable and untimely deaths. According to the mortality survey in a prison in London between 1795 and 1829,13) suicides by hanging had occurred during that period as well and, except for cases without stated causes of death, 'Visitation of God' was the most common cause, perhaps as a coroner's whitewashing rephrases describing deaths in prison. In hindsight, it is still unclear what it meant exactly, but some sudden deaths by cardiovascular disease might be included. Just as it is these days, this ancient report implies 'nothing new under the sun' - nearly 200 years before today. Nevertheless, there are still something to learn from this report, and based on this study, we can urge the authorities to focus their effort on reducing the occurrences of death in police custody and incarceration.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Saukko P, Knight B. Knight's forensic pathology. 2004. 3rd ed. London: Edward Arnold Ltd;305–311.

2. Freckelton I. Safeguarding the vulnerable in custody. J Law Med. 2009. 17:157–164.

3. Kariminia A, Law MG, Butler TG, et al. Factors associated with mortality in a cohort of Australian prisoners. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007. 22:417–428.

4. Pompili M, Lester D, Innamorati M, et al. Preventing suicide in jails and prisons: suggestions from experience with psychiatric inpatients. J Forensic Sci. 2009. 54:1155–1162.

5. Wobeser WL, Datema J, Bechard B, Ford P. Causes of death among people in custody in Ontario, 1990-1999. CMAJ. 2002. 167:1109–1113.

6. The Constitution of the Republic of Korea. Ministry of Government Legislation. Available from http://www.law.go.kr/lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=61603#0000.

7. Davis N. Death in custody. J R Soc Med. 1999. 92:611.

8. O'Driscoll C, Samuels A, Zacka M. Suicidein New South Wales Prisons, 1995-2005: towards a better understanding. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007. 41:519–524.

9. 339 recommendations in the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in custody (1991) final report. Available from http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/IndigLRes/rciadic/national/vol5/5.html#Heading5.

10. Kim JY, Park S, Ha H. Stab Injury and Death, Related with TASER(R) Gun: A Case Report and Literature Reviews. Korean J Leg Med. 2010. 34:129–132.

11. Lee BK, Vittinghoff E, Whiteman D, Park M, Lau LL, Tseng ZH. Relation of Taser (electrical stun gun) deployment to increase in in-custody sudden deaths. Am J Cardiol. 2009. 103:877–880.

12. Jauchem JR. Deaths in custody: are some due to electronic control devices (including TASER devices) or excited delirium? J Forensic Leg Med. 2010. 17:1–7.

13. Forbes TR. A mortality record for Coldbath Fields Prison, London, in 1795-1892. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1977. 53:666–670.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download