Abstract

Purpose

This study was done to develop a prediction model for postpartum depression by verifying the mediation effect of antepartum depression. A hypothesized model was developed based on literature reviews and predictors of postpartum depression by Beck.

Methods

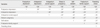

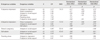

Data were collected from 186 pregnant women who had a gestation period of more than 32 weeks and were patients at a maternity hospital, two obstetrics and gynecology specialized hospitals, or the outpatient clinic of K medical center. Data were analysed with descriptive statistics, correlation and exploratory factor analysis using the SPSS/WIN 18.0 and AMOS 18.0 programs.

Results

The final modified model had good fit indices. Parenting stress, antepartum depression and postpartum family support had statistically significant effects on postpartum depression, and defined 74.7% of total explained variance of postpartum depression. Antepartum depression had significant mediation effects on postpartum depression from stress in pregnancy and self-esteem.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that it is important to develop nursing interventions including strategies to reduce parenting stress and improve postpartum family support in order to prevent postpartum depression. Especially, it is necessary to detect and treat antepartum depression early to prevent postpartum depression as antepartum depression can affect postpartum depression by mediating antepartum factors.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Smith M, Jaffe J. Depression in women: Causes, symptoms, treatment, and self-help [Internet]. Santa Monica, CA: Helpguide;2014. cited 2014 March 3. Available from: http://www.helpguide.org/articles/depression/depression-in-women.htm.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Depression among women of reproductive age [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: Author;2013. cited 2014 April 11. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/Depression/.

3. Park YJ, Shin HJ, Ryu HS, Cheon SH, Moon SH. The predictors of postpartum depression. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2004; 34(5):722–728.

4. Cho HJ, Choi KY, Lee JJ, Lee IS, Park MI, Na JY, et al. A study of predicting postpartum depression and the recovery factor from prepartum depression. Korean J Perinatol. 2004; 15(3):245–254.

5. Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: An update. Nurs Res. 2001; 50(5):275–285.

6. Youn JH, Jeong IS. Predictive validity of the postpartum depression predictors inventory-revised. Asian Nurs Res. 2011; 5(4):210–215. DOI: 10.1016/j.anr.2011.11.003.

7. Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: A synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004; 26(4):289–295. DOI: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006.

8. Kim JY, Kim JG. Psycho-social predicting factors model of postpartum depression. Korean J Health Psychol. 2008; 13(1):111–140.

9. Cho HW, Woo JY. The relational structure modeling between variables related with postpartum depression. Korean J Couns Psychother. 2013; 25(3):549–573.

10. Leigh B, Milgrom J. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry. 2008; 8:24. DOI: 10.1186/1471-244x-8-24.

11. Bae JY. Construction of a postpartum depression model. J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2002; 11(4):572–587.

12. Kim KS, Kam S, Lee WK. The influence of self-efficacy, social support, postpartum fatigue and parenting stress on postpartum depression. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2012; 16(2):195–211.

13. Chandran M, Tharyan P, Muliyil J, Abraham S. Post-partum depression in a cohort of women from a rural area of Tamil Nadu, India Incidence and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 2002; 181:499–504.

14. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; 150:782–786.

15. Han K, Kim M, Park JM. The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, Korean version: Reliability and validity. J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry. 2004; 10(2):201–207.

16. Park JW. A study to development a scale of social support. J Nurs Sci. 1986; 9(1):22–31.

17. Song JM. In the parenting stress situation, the effect of social support to parental perceptions of child behavior [master's thesis]. Seoul: Sookmyoung Women's University;1992.

18. Ahn HL. An experimental study of the effects of husband's supportive behavior reinforcement education on stress relief of primigravidas. J Nurs Acad Soc. 1985; 15(1):5–16.

19. Jo JA, Kim YH. Mothers' prenatal environment, stress during pregnancy, and children's problem behaviors. J Hum Ecol. 2007; 11(2):43–62.

20. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press;1965.

21. Jon BJ. Self-esteem: A test of its measurability. Yonsei Forum. 1974; 11(1):107–130.

22. Lee J, Nam S, Lee MK, Lee JH, Lee SM. Rosenberg' self-esteem scale: Analysis of item-level validity. Korean J Couns Psychother. 2009; 21(1):173–189.

23. Hopkins J, Campbell SB, Marcus M. Role of infant-related stressors in postpartum depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1987; 96(3):237–241.

24. Cutrona CE. Social support and stress in the transition to parenthood. J Abnorm Psychol. 1984; 93(4):378–390.

25. Cheon JA. The effect of postpartum stress and social network on the postpartum [master's thesis]. Seoul: Korea University;1990.

26. Kwon JH. A test of a vulnerability-stress model of postpartum depression. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1997; 16(2):55–66.

27. Silva R, Jansen K, Souza L, Quevedo L, Barbosa L, Moraes I, et al. Sociodemographic risk factors of perinatal depression: A cohort study in the public health care system. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012; 34(2):143–148.

28. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.;2013.

29. Lee MK. A structural model for depression during pregnancy [dissertation]. Daejeon: Eulji University;2014.

30. Choi MR, Lee IH. The moderating and mediating effects of self-esteem on the relationship between life stress and depression. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2003; 22(2):363–383.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download