Abstract

Purpose

This study was done to explore experiences of persons living through the periods of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and self-care.

Methods

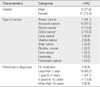

With permission, texts of 29 cancer survival narratives (8 men and 21 women, winners in contests sponsored by two institutes), were analyzed using Kang's Korean-Computerized-Text-Analysis-Program where the commonly used Korean-Morphological-Analyzer and the 21st-century-Sejong-Modern-Korean-Corpora representing laymen's Korean-language-use are connected. Experiences were explored based on words included in 100 highly-used-morphemes. For interpretation, we used 'categorizing words by meaning', 'comparing use-rate by periods and to the 21st-century-Sejong-Modern-Korean-Corpora', and highly-used-morphemes that appeared only in a specific period.

Results

The most highly-used-word-morpheme was first-person-pronouns followed by, diagnosis·treatment-related-words, mind-expression-words, cancer, persons-in-meaningful-interaction, living and eating, information-related-verbs, emotion-expression-words, with 240 to 0.8 times for layman use-rate. 'Diagnosis-process', 'cancer-thought', 'things-to-come-after-diagnosis', 'physician·husband', 'result-related-information', 'meaningful-things before diagnosis-period', and 'locus-of-cause' dominated the life of the diagnosis-period. 'Treatment', 'unreliable-body', 'husband · people · mother · physician', 'treatment-related-uncertainty', 'hard-time', and 'waiting-time represented experiences in the treatment-period. Themes of living in the self-care-period were complex and included 'living-as-a-human', 'self-managing-of-diseased-body', 'positive-emotion', and 'connecting past · present · future'.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Carroll-Johnson RM, Gorman LM, Bush NJ. Psychosocial nursing care along the cancer continuum. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Press;2006.

2. Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kraemer J, Wright K, Coscarelli A, et al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: A qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2004; 13(6):408–428. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.750.

3. Szegedy-Maszak M, Hobson K. Beating a killer. US News World Rep. 2004; 136(11):56–58.

4. National Cancer Center. Cancer incidence in Korea, 2010 [Internet]. Goyang: Author;2014. cited 2014 March 21. Available from: http://ncc.re.kr/english/infor/kccr.jsp.

5. Yang JH. The actual experiences of the living world among cancer patients. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2008; 38(1):140–151. http://dx.doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2008.38.1.140.

6. Yi M, Park EY, Kim DS, Tae YS, Chung BY, So HS. Psychosocial adjustment of low-income Koreans with cancer. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2011; 41(2):225–235. http://dx.doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2011.41.2.225.

7. Anderson C. Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010; 74(8):141.

8. Park HS, Cho GY, Park KY. The effects of a rehabilitation program on physical health, physiological indicator and quality of life in breast cancer mastectomy patients. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2006; 36(2):310–320.

9. Pennebaker JW. Current issues and new directions in psychology and health: Listening to what people say-the value of narrative and computational linguistics in health psychology. Psychol Health. 2007; 22(6):631–635. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870440701414920.

10. Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.;1998.

11. Francis ME, Pennebaker JW. Putting stress into words: The impact of writing on physiological, absentee, and self-reported emotional well-being measures. Am J Health Promot. 1992; 6(4):280–287.

12. Lee GH, Kang NJ, Lee JY. The study on rhetoric of president Moo-Hyun Noh in impeachment period: Focusing on computerized text analysis program. Korean J Journal Commun Stud. 2008; 52(5):25–55.

13. Cho MA, Kim DS. Changes in attitudes of Korean terminal cancer patients family members about palliative sedation for controlling refractory symptoms: Before to after sedative injection. Poster session presented at: The 10th Asia Pacific Hospice Conference 2013. 2013 October 11-13; Bangkok Convention Centre at Central World, Bangkok, TH.

14. Jeong HW, Lee YJ. Cognitive map for the strongest presidential candidate through running in election: Content analysis of declaration running for president and analysis of semantic network. EAI OPINION Rev Ser. 2012; 2012(7):1–10.

15. Kang B. Building corpora and making use of frequency (statistics) for linguistic descriptions. J Korealex. 2008; 12:7–40.

16. Pennebaker JW, Chung CK. Expressive writing, emotional upheavals, and health. In : Friedman H, Silver R, editors. Handbook of health psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press;2007. p. 263–284.

17. Stirman SW, Pennebaker JW. Word use in the poetry of suicidal and nonsuicidal poets. Psychosom Med. 2001; 63(4):517–522.

18. Pennebaker JW, Pennebaker JW, Mehl MR, Niederhoffer KG. Psychological aspects of natural language use: Our words, our selves. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003; 54:547–577. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145041.

19. Gardner WL, Gabriel S, Lee AY. "I" value freedom, but "We" value relationships: Self-construal priming mirrors cultural differences in judgment. Psychol Sci. 1999; 10(4):321–326. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00162.

20. Boyle DA. Survivorship. In : Carroll-Johnson RM, Gorman LM, Bush NJ, editors. Psychosocial nursing care along the cancer continuum. 2nd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Press;2006. p. 25–51.

21. Skott C. Expressive metaphors in cancer narratives. Cancer Nurs. 2002; 25(3):230–235.

22. Halldórsdóttir S, Hamrin E. Caring and uncaring encounters within nursing and health care from the cancer patient's perspective. Cancer Nurs. 1997; 20(2):120–128.

23. Kwon EJ, Yi M. Distress and quality of life in breast cancer survivors in Korea. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2012; 12(4):289–296. http://dx.doi.org/10.5388/aon.2012.12.4.289.

24. Conrad P, Barker KK. The social construction of illness: Key insights and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010; 51:Suppl. S67–S79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383495.

25. Hupcey JE. Clarifying the social support theory-research linkage. J Adv Nurs. 1998; 27(6):1231–1241.

26. Hobfoll SE, Cameron RP, Chapman HA, Gallagher RW. Social support and social coping in couples. In : Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG, editors. Handbook of social support and the family. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media;1996. p. 413–433.

27. Cho J, Smith K, Choi EK, Kim IR, Chang YJ, Park HY, et al. Public attitudes toward cancer and cancer patients: A national survey in Korea. Psychooncology. 2013; 22(3):605–613.

28. Beck SJ, Keyton J. Facilitating social support: Member-leader communication in a breast cancer support group. Cancer Nurs. 2014; 37(1):E36–E43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182813829.

29. Krumwiede KA, Krumwiede N. The lived experience of men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012; 39(5):E443–E450. http://dx.doi.org/10.1188/12.onf.e443-e450.

30. Wang JJ, Hsieh PF, Wang CJ. Long-term care nurses' communication difficulties with people living with dementia in Taiwan. Asian Nurs Res. 2013; 7(3):99–103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2013.06.001.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download