Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to translate the Spiritual Perspective Scale (SPS) and Self-transcendence Scale (STS) into Korean and test the psychometric properties of the instruments with Korean elders.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey design was used to implement the three stages of the study. Stage I consisted of translating and reviewing the scales by six experts. In Stage II, equivalence was tested by comparing the responses between the Korean and English versions among 71 bilingual adults. Stage III established the psychometric properties of the Korean versions SPS-K and STS-K among 154 Korean elders.

Results

Cronbach's alpha of the SPS-K and the STS-K .97, and .85 respectively with Korean elders. Factor analysis showed that the SPS-K had one factor; the STS-K had four factors with one factor clearly representing self-transcendence as theorized. Both scales showed good reliability and validity for the translated Korean versions. However, continued study of the construct validity of the STS-K is needed.

Conclusion

Study findings indicate that the SPS-K and the STS-K could be useful for nurses and geriatric researchers to assess a broadly defined spirituality, and to conduct research on spirituality and health among Korean elders. Use of these scales within a theory-based study may contribute to further knowledge about the role of spirituality in the health and well-being of Korean people facing health crises.

In the last few decades, nursing and other health-related disciplines have examined the effect of spirituality on mental and physical health worldwide (Delaney, Barrere, & Helming, 2011; Koenig, 2008; Sessanna, Finnell, & Jezewski, 2007). Spirituality provides a salient resource to help older adults cope with declining physical and mental health and with other losses and death that occur in later life (Callen, Mefford, Groer, & Thomas, 2011; Kim, Reed, Hayward, Kang, & Koenig, 2011). The findings from many studies indicate that spirituality among older adults has been positively correlated with greater social support, higher life satisfaction, less depression, better cognitive function, and higher psychological and physical well-being (Boswell, Kahana, & Dilworth-Anderson, 2006; Kim et al.; Lee, 2007). Spirituality is a broad and multidimensional concept which has may different meanings and interpretations. Thus, spirituality is defined and measured by several different spiritually-related variables such as forgiveness, gratitude, hope, spiritual well-being, spiritual perspective, meaning and purpose in life, self-transcendence, connectedness, religious coping mechanisms, and religious beliefs and practices (Koenig).

A considerable number of studies have demonstrated a significant relationship between spirituality and well-being, but most have focused on spirituality and religion in Western cultures and the Christian tradition (Lee, 2007). Little is known about Korean elders' experience of spirituality and its relationship to health or well-being in Korean culture. A few investigators have reported that spirituality among Korean older adults is positively related to acceptance of death, satisfaction with life, positive and negative affect, depression, subjective well-being, and physical health such as physical function, and health promoting behaviors (Jang & Kim, 2003; Kim et al., 2011; Lee; Lee & Oh, 2003). However, these studies used the Spiritual Well-Being Scale developed by Paloutzian and Ellison (1982), which confounds measures of emotional well-being with spirituality (Koenig, 2008). The lack of instruments in the Korean language to measure the broad concept of spirituality has limited research into the potential health-related influences of spirituality among Korean elders. There is a need to establish measures of spirituality that are psychometrically sound for research with Korean individuals. Thus, the goal of this measurement study was to provide researchers with two psychometrically sound spirituality instruments that have been translated into the Korean language. Through use of these instruments, researchers may gain a better understanding of spiritually-related factors that influence physical and mental health outcomes in Korean elders.

The Spiritual Perspective Scale (SPS) and Self-transcendence Scale (STS) developed by Reed (1986; 1987) have been widely used to measure spirituality that is more broadly defined. The theory of Self-transcendence (Reed, 2008) served as the theoretical basis for defining a spiritual perspective and self-transcendence. This theory was developed to explain the process of self-transcendence as related to physical and psychological well-being in older adults facing life-threatening illness and end-of-life challenges. Self-transcendence is defined as the expansion of self-boundaries in a way that enhances awareness of self and broadens life perspectives (Reed, 2008). Some of the ways a person can expand self-boundaries are intrapersonally (within one's inner potential and experiences); interpersonally (reaching out to others or to one's environment); and temporally (whereby the meaning of the present integrates with the past and future) (Reed, 2008). A spiritual perspective is a form of self-transcendence that emphasizes expanding self-boundaries transpersonally through prayer, meditation, forgiveness, and belief in God or a higher purpose; there is a distinct sense of connectedness to something greater than the self (Reed, 1991). The SPS was developed to measure the saliency of a spiritual perspective and practices in a person's life (Reed, 1987). The STS was developed to measure various experiences of self-transcendence from a more terrestrial than transpersonal view, such as expansion of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and temporal self-boundaries that occur with an increased awareness of mortality such as in life-threatening illness, bereavement, or advanced age (Reed, 1991; 2008).

The SPS and STS have been translated into several languages such as Japanese, Persian, Spanish, and Swedish to examine spiritually-related variables in various cultural backgrounds across adulthood ages, especially older adults (Hoshi, 2008; Nygren et al., 2005; Rohani, Khanjari, Abedi, Oskouie, & Langius-Eklof, 2010). However, the instruments had not been translated into Korean. Therefore, it was necessary to develop a reliable and valid Korean translation of the SPS and the STS to facilitate spiritually-related research on health and well-being among people in Korea and in cross-cultural research. Although the translated versions of the SPS-K and STS-K could be applied to any Korean adult population, the reliability and validity of the Korean versions of the SPS-K and the STS-K were tested in this study with Korean older adults because of the specific need for research on how spiritual perspective and self-transcendence relate to emotional well-being in this population. Both instruments were originally developed for use with adults facing end of life through aging or serious illness experiences, and there is abundant research on these instruments with non-Korean older adults with which to compare findings. In addition, reliable and valid Korean versions of the SPS and the STS may be useful for assessing spiritual perspective and self-transcendence for nursing practice or research with Korean older adults.

The specific purposes of this study were to: a) translate the Spiritual Perspective Scale (SPS) and the Self-transcendence Scale (STS) into Korean (Stage I); b) compare the translated Korean versions to the original English versions to test equivalence and their reliability in using a bilingual sample (Stage II); and c) test the reliability and validity of the Korean versions of the SPS-K and the STS-K with Korean elders (Stage III).

Cross-sectional survey designs were used to implement each of the three stages of the study. To test equivalence between the original English and translated Korean versions of the instruments, Hilton and Skrutkowski (2002) recommended several methods including expert review, response comparisons, and psychometric examination. Through a translation process (Stage I), experts reviewed the translations for clarity and linguistic appropriateness. In Stage II, responses to the two language versions were compared by bilingual persons. Stage III determined the psychometric properties of the translated Korean versions of the SPS-K and the STS-K among Korean elders.

The SPS was developed by Reed (1987) to measure the saliency of a transcendent perspective with emphasis on spirituality and that may include traditional or nontraditional religious perspectives. The 10 items of the SPS elicit data about a person's spiritual views and practices. Each item is scored on a 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all/strongly disagree) to 6 (about one a day/strongly agree). The means across all items are summed and divided by the number of items for the total score. Possible scores range from 1.0 to 6.0; higher scores indicate a greater spiritual perspective. Research findings support construct and criterion-related validity and reliability, which consistently have been found to be .90 or above with no redundancy in inter-item correlations. The SPS has been widely used in numerous studies with elders, caregivers and patients with various chronic illnesses and has maintained a reliability of .92 to .94 (Dailey & Steward, 2007; Gray, 2006; Jesse & Reed, 2004; Reed, 1987).

The STS, developed by Reed (1986), consists of 15 items to measure self-transcendence which is the capacity of individuals to expand self-boundaries inwardly in introspective activities, outwardly in concern for others, transpersonally as a focus on things greater than the self, and temporally as the past and future may affect the present (Reed, 1986). Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much), with reverse-scoring on item 15. The total score is calculated by summing across items and dividing by items completed. Possible scores range from 1.0 to 4.0; a higher score indicates greater self-transcendence. The STS is a unidimensional scale, which has one factor representing expansion of self-boundaries (such as inwardly, outwardly, temporally, and transpersonally). The STS emphasizes psychosocial experiences and expressions of spirituality. It has demonstrated acceptable construct validity and reliability, with coefficients generally found to be around .80 to as high as .94. It has been used with many populations of various ethnicities and across adulthood ages, especially older adults; and with well and ill patient groups; breast cancer survivors and patients; and with family caregivers and professional nurses (Bean & Wagner, 2006; Chen & Walsh, 2009; Reed, 1991; Thomas, Burton, Quinn Griffin, & Fitzpatrick, 2010).

Three distinct stages, including 5 steps in Stage I, were implemented to translate and test each instrument. Stages II and III were distinct studies designed to test various psychometric properties of each instrument. The results of these studies are discussed in the Results section.

The revised Brislin's (1970) translation process, adapted by Jones, Lee, Phillips, Zhang, and Jaceldo (2001), was undertaken to develop the translated Korean versions of the SPS and STS. An adaptation and extension of Brislin's process included simultaneous translations and back-translations followed by group discussion by bilingual experts (Jones et al.). In this study, semantic and conceptual equivalence were considered and established. Semantic equivalence refers to the similarity of meaning of each item and conceptual equivalence indicates that the instrument measures the same theoretical construct across two cultures (Hilton & Skrutkowski, 2002). While an emic perspective, which emphasizes the meaning of concepts in one culture, makes it difficult to translate some concepts or specific items into different cultures (Jones et al.), we used a derived etic view (Berry, 1969) which combined both emic and etic perspectives to guide the translation and to facilitate semantic and conceptual equivalence culturally and linguistically. Thus, the translators ensured that the meaning of each item was conceptually and idiomatically appropriate and familiar to the contextual meaning in both American and Korean cultures. Six bilingual translators with a bicultural background in Korean and English including 3 nursing professors, 1 linguistic professor, and 2 nurses participated in the translation procedure. Permission to use and to translate the SPS and the STS into Korean was obtained from Dr. Reed prior to the study (Kim et al., 2011).

The translation procedure consisted of 5 steps (see Figure 1). In Step 1, two independent translators (A and B) simultaneously translated the instruments from English into Korean and developed two initial Korean versions (K1 and K2). In Step 2, two new translators (C and D) who did not see the original versions (SPS and STS) blindly back-translated and created two back-translations (BT1 and BT2). Step 3 consisted of group discussion and synthesis. A group discussion was held to check the cultural and linguistic equivalence between the original and the two back-translated versions produced in Step 2. Translators A, B, C and D reviewed and compared the two initial Korean versions (K1 and K2), back-translations (BT1 and BT2), and the original English versions (SPS and STS) to determine the most accurate and easily comprehensible terms as culturally equivalent meanings. For example, the SPS term "higher being" in English matched a phrase "god of heaven and earth" in Korean because shamanistic Koreans worship the heavens and earth (Oak, 2010). The STS English phrase "Dwelling on my past unmet dreams or goals" was interpreted into Korean as "Living regretfully with my past unmet dreams or goals". After the translators discussed the content, semantics and conceptual equivalence and discrepancies through their derived etic view, they obtained a single Korean version (K3). In Step 4, two translators (E and F) independently and blindly back-translated new versions (BT3 and BT4) from the Korean versions (K3) produced in Step 3. In Step 5, translators A, B, C and D had a second group discussion to review the new back translations (BT3 and BT4). At this time, all four translators agreed on the cultural equivalence between the source and target language versions of the instruments and created the final Korean versions (SPS-K and STS-K).

In this stage, a study was designed to compare the translated Korean versions to the original English versions and to test equivalence and reliability. Both the English and Korean versions of each instrument (SPS and STS) were administered to bilingual persons who were familiar with both languages and cultures.

Participants were recruited from local Korean churches and the Diamond Zen temple in Tucson, AZ, USA from January 1, 2006 to June 30, 2006. The Consent Form, demographic questionnaires and both the original English and Korean versions of the SPS and the STS were administered to 71 persons who were bilingual speakers of English and Korean and 21 years of age or older. The English and Korean versions of the SPS and the STS were randomly arranged in a counterbalanced order so that approximately half of the participants were administered the English version first, and half the Korean version first. The final sample size of 71 was sufficient to detect a moderately small effect (Cohen's d=.34) with power of .80 and two-tailed alpha=.05 for Paired sample t-test and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

The ICC and Paired sample t-tests were used to compare the responses on each item, and total scores between the English and Korean versions to test equivalence. A larger ICC (>.80) indicates a higher degree of correlation and non-significant differences between the two versions. Also, equivalence was investigated by asking the bilingual participants who had completed both Korean and English versions whether they thought the two versions were equivalent or not. Reliability, the degree of internal consistency of the new Korean versions and the original English versions of the SPS and the STS, was tested using Cronbach's alpha coefficients. All statistical analyses in this study were performed using SPSS (version 18.0). Stage II results, reported below, were positive and allowed progression to Stage III.

The Korean versions of the two instruments developed in Stage II were further analyzed in Stage III. In this stage, a study was implemented to test the reliability and validity of each instrument (SPS-K and STS-K) in a sample of Korean elders.

A convenience sampling method was used to recruit 230 Korean elders from welfare centers, community centers for elders, and religious institutions (e.g., churches and temples) in Seoul Korea from March 1, 2007 to June 30, 2007. Recruitment strategies included use of flyers and announcements in community bulletins. Elders were eligible if they were: a) 60 years of age or older; b) able to read or speak Korean; and c) had no serious cognitive disorders (to ensure their ability to communicate clearly with an interviewer and complete questionnaires). They were asked basic demographic questions (e.g., name, birth date, age, address, telephone number, and current date) to assess their cognitive and communication abilities. Thirty-eight elders were excluded due to significant impairment or difficulty with communicating. Thirty-five elders were excluded for not completing the questionnaires. Of the 230 recruited, 157 elders (68.3%) completed self-administered questionnaires. With a total of 25 items across instruments, a minimum sample size of 125 participants was needed according to Floyd and Widaman's (1995) suggestion of a 5:1 ratio of participants to variables for exploratory factor analysis.

Reliability was estimated by Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The item-total correlations of the SPS-K and the STS-K were analyzed to examine whether each item correlated strongly with the scale. A minimum item-total correlation level of .20 was set for inclusion in the scale (George & Mallery, 2011). To assess the construct validity, exploratory factor analysis using the principal component analysis with a Varimax rotation was used to examine the underlying factor structure. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett's test of sphericity (BT) were examined to determine the adequacy of the data for factor analysis. In this study, the factor loading criterion was set at .40. The cutoff criterion of an eigenvalue greater than 1.0 was used to select the number of factors (George & Mallery). Convergent validity was tested by examining the theorized relationships between the SPS-K and the STS-K.

Two studies for Stages II and III each received Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Arizona's Human Subject Committee (IRB #B05.275 and #B07.021). The written subjects' consent form was obtained from each participant prior to administering the questionnaires.

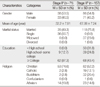

Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. Seventy-one bilingual (English/Korean) persons, 38 men and 33 women, participated in this study. Their ages ranged from 21 to 62 with a mean age of 32±7.91. All participants had a high school education.

In this sample of 71 bilingual persons, the reliability of the SPS-K (α=.97) was similar to the original English version of the SPS (α=.96). The reliability of the STS-K was .77, the same as that found in the original English version of the STS (α=.77). Both results were above the .70 criterion for acceptable internal consistency (George & Mallery, 2011). Similar coefficients of internal consistency between the two language versions supported equivalence. The means, standard deviations, and reliability of the two scales are shown in Table 2.

Table 3 and 4 presents the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the SPS and STS. There were significant correlations between the new Korean versions and the original English versions: the SPS (r=.99, p<.01), and the STS (r=.95, p<.01). Also, significant and high correlations were found between each SPS item responses on both language versions, which ranged from .95 (item 1) to .99 (item 2, 3, 7 and 9) (see Table 3). There were significant and high correlations between STS item responses, which ranged from .81 (item 4) to .97 (item 3) (see Table 4). Moreover, paired t-test comparisons of responses on each item and between total scores indicated that there were no significant differences between the two versions of the two instruments. Furthermore, the bilingual participants reported that the two versions were equivalent after they completed both the Korean and English versions. Findings supported equivalence between the two language versions.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the 157 Korean elders who participated in the study. The sample consisted of 86 males and 71 females. Ages ranged from 60 years to 94 years with a mean age of 68±7.24. Only two participants (1%) were over 90 years old, but both were able to clearly communicate with the interviewer to complete the questionnaires.

Cronbach's alpha of the SPS-K with Korean elders was .97. The mean of the inter-item correlation of the SPS-K was .79 (with a range of .65 to .90), and the corrected item-total correlations ranged from .80 to .93 (see Table 3). Statistically significant and high item-total score correlations indicated that the direction of scoring was correct for all items and that each item contributed significantly to the total score.

Cronbach's alpha of the STS-K was .85. The mean inter-item correlation of the STS-K was .29 (with a range of .23 to .58), and the corrected item-total correlations were from .12 to .61 (see Table 4). The reverse-scored item 15, "Dwelling on my past unmet dreams or goals" weakly correlated with the summated score for all other items (r=.12). It failed to meet a minimum item-total correlation level of .20 for inclusion in the scale (George &Mallery, 2011). This item has performed similarly in previous research. However, removal of this item did not significantly increase the alpha coefficients (α=.87). These findings support that both the SPS-K and the STS-K had good internal consistency. (See Table 2 for the means, standard deviations, and reliability from the Stage III testing).

Construct validity of the SPS-K was examined using Principal-Component Factor Analysis with a Varimax rotation. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy and BT indicated that the data were appropriate for factor analysis (KMO=.95; χ2 (45)=2107.11, p<.01). Factor analysis of the SPS-K showed that only one factor was extracted with an eigenvalue >1. This factor had an eigenvalue of 8.01 and accounted for 80.93% of the variance. Further examination of the factor loading of each item on this factor showed that all 10 items were highly loaded on the one factor, which had a common theme of spiritual perspective. Table 3 presents factor loading of each item on the single factor of the SPS-K.

Table 4 presents factor loading of each item on the four factors of the STS-K. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy and BT supported the adequacy of the data for factor analysis (KMO=.86; χ2 (105)=799.535, p<.01). Using the principal axis factoring extraction method with an eigenvalue >1, four factors were extracted and explained 59.36% of the total sample variance. The first largest factor had an eigenvalue of 5.43 and accounted for the largest percentage (36.19%) of the variance: the seven highly loaded items were 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, and 14. The second factor explained 8.62% of the variance and Items 4, 5, 7, 11, and 12 correlated most highly with it. A third factor accounted for 7.58% of the variance with Items 12 and 13 loading on this factor. Lastly, the fourth factor accounted for 6.97% of the variance with loadings from items 10 and 15. The exploratory factor analysis generated one primary factor that contained a representative group of items on expanding self-boundaries outwardly and inwardly. This finding lent some support to construct validity.

This research involved three stages of empirical work to translate the SPS and the STS into Korean, to test for equivalence between the English and Korean versions, and then to examine the reliability and validity of the SPS-K and the STS-K. The research process and outcomes overall indicated that the use of the 3-stage approach was an efficient yet effective approach to instrument translation. The translation process (Stage I) showed that the revised Brislin model by Jones and colleagues (2001) was an appropriate method to translate the SPS and the STS into Korean. The derived etic approach facilitated achievement of semantic and conceptual equivalence between the English and Korean versions of the two instruments. Also, Hilton and Skrutkowski (2002) suggested that translators be familiar with the study area and include experts, professional interpreters, people who are bilingual in either the source language as their first language or in the target language as their first language, and people who are monolingual and representative of the populations being studied. Consistent with their suggestion, we used six bilingual translators who were all familiar with the concept of spirituality and included three nursing researchers as experts, one linguistic professor as a professional interpreter, and two nurses in the translation procedure. Moreover, in Stage II, we tested cultural and linguistic equivalence by comparing responses to the original English and translated Korean versions among 71 bilingual persons who were bilingual speakers of English and Korean with a bicultural background. The results supported that the two languages of the instruments achieved their semantic and conceptual equivalence.

In Stage III, the results of this study indicated that the SPS-K and the STS-K demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity. Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the SPS-K was very good, as in the English version (Dailey & Steward, 2007; Gray, 2006; Jesse & Reed, 2004; Reed, 1987). Factor analyses confirmed that the SPS-K had a single factor structure as that of the original English version (Reed, 1987). The STS-K showed an acceptable alpha reliability estimate, similar to results reported for the English version (Bean & Wagner, 2006; Chen & Walsh, 2009; Reed, 1991; Thomas et al., 2010). However, item analysis found that a reverse item 15, "Dwelling on my past unmet dreams or goals", weakly correlated with the overall measure. In the translation process, experts were unable to find the word in Korean which has same meaning of a phrase "dwelling on" in English. Hence, the English phrase "Dwelling on my past unmet dreams or goals" was interpreted into Korean as "Living regretfully with my past unmet dreams or goals". This item has had problems for research with the English version as well. Regardless of the lower item-total correlations of item 15, we decided to keep it in the STS-K because there was no significant increase in Cronbach's alpha when it was left out.

While the results indicated that cultural and linguistic equivalence were achieved in the STS-K, more research is needed regarding the construct validity. The four factors extracted in the exploratory factor analysis were not consistent with the STS as a unidimensional instrument (Reed, 1986). However, the strongest factor represented well the conceptualization of self-transcendence as expanding self-boundaries in multiple ways. In addition, the second strongest factor was interpretable in terms of behaviors that focus on expanding boundaries intrapersonally (e.g., finding inner meanings and adjusting to one's limitations). So, in this sense, the STS-K does demonstrate some construct validity. Future research should more closely examine the instruments' content validity and meanings of self-transcendence, for example, by using focus groups of Koreans from differing religious and social groups. In sum, Stage III results, based on a psychometric study involving 157 Korean elders, supported reliability as estimated by Cronbach's alpha, construct validity, and convergent validity for both instruments. However, more research is needed to further understand the meaning of self-transcendence in the context of different Korean spiritual and religious views.

In terms of limitations of the study, some elements of the study design and sample composition limit the scope of the conclusions that may be drawn from the analyses. The use of a convenience sample limits generalizability of the results. For example, Korean elders who participated in this study were living in Seoul, Korea and were relatively well-educated. The application of the SPS-K and the STS-K to elders living in rural Korea or who are less educated requires further evaluation. Future studies should incorporate broader samples to better establish the reliability and validity in various Korean populations.

Our results support that the Korean versions of the SPS-K and the STS-K have adequate reliability and validity. The SPS-K and the STS-K would be able to measure the broad concept of spirituality and facilitate research on spirituality and health in Korea as well as in cross-cultural research. Applying these instruments within theory-based research may contribute to knowledge about the role of spirituality in the health and well-being of Korean elders facing health crises. Researchers may gain a better understanding of spiritually-related factors that influence physical and mental health outcomes in Korean elders. For nursing practice, the SPS-K and STS-K have the potential to assess spiritually-related variables and evaluate their relationships to health and well-being outcomes among Korean elders. Culturally sensitive and valid instruments could foster nursing education for providing spiritual care among Korean elders. However, the Korean versions of the SPS-K and the STS-K may be used by researchers who are mindful of the need for continued evaluation of the reliability and validity in their research samples. The instruments can be obtained from the copyright owner of these instruments, namely Dr. Kim, Suk-Sun for the Korean versions, and Dr. Pamela Reed for the English versions of the SPS (Reed, 1987) and the STS (Reed, 1986).

Figures and Tables

References

1. Bean KB, Wagner K. Self-transcendence, illness distress, and quality of life among liver transplant recipients. J Theory Constr Test. 2006. 10(2):47–53.

2. Berry JW. On cross-cultural comparability. Int J Psychol. 1969. 4(2):119–128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00207596908247261.

3. Boswell GH, Kahana E, Dilworth-Anderson P. Spirituality and health lifestyle behaviors: Stress counter-balancing effects on the well-being of older adults. J Relig Health. 2006. 45(4):587–602. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10943-006-9060-7.

4. Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970. 1(3):185–216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301.

5. Callen BL, Mefford L, Groer M, Thomas SP. Relationships among stress, infectious illness, and religiousness/spirituality in community-dwelling older adults. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2011. 4(3):195–206. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/19404921-20101001-99.

6. Chen S, Walsh SM. Effect of a creative-bonding intervention on Taiwanese nursing students' self-transcendence and attitudes toward elders. Res Nurs Health. 2009. 32:204–216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nur.20310.

7. Dailey DE, Steward AL. Psychometric characteristics of the Spiritual Perspective Scale in pregnant African-American women. Res Nurs Health. 2007. 30:61–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nur.20173.

8. Delaney C, Barrere C, Helming M. The influence of a spirituality-based intervention on quality of life, depression, and anxiety in community-dwelling adults with cardiovascular disease: A pilot study. J Holist Nurs. 2011. 29(1):21–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0898010110378356.

9. Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychol Assess. 1995. 7:286–299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.286.

10. George D, Mallery P. SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 18.0 update. 2011. 11th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

11. Gray J. Measuring spirituality: Conceptual and methodological considerations. J Theory Constr Test. 2006. 10(2):58–64.

12. Hilton A, Skrutkowski M. Translating instruments into other languages: Development and testing processes. Cancer Nurs. 2002. 25(1):1–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002820-200202000-00001.

13. Hoshi M. Self-transcendence, vulnerability, and well-being in hospitalized Japanese elders. 2008. Tucson, USA: University of Arizona;Unpublished doctoral dissertation.

14. Jang E, Kim S. Study on spiritual well-being of elderly people in the community. J Korean Gerontol Nurs. 2003. 5(2):193–204.

15. Jesse DE, Reed PG. Effects of spirituality and psychosocial well-being on health risk behaviors in Appalachian pregnant women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004. 33:739–747. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0884217504270669.

16. Jones PS, Lee JW, Phillips LR, Zhang XE, Jaceldo KB. An adaptation of Brislin's translation model for cross-cultural research. Nurs Res. 2001. 50(5):300–304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200109000-00008.

17. Kim SS, Reed PG, Hayward RD, Kang Y, Koenig HG. Spirituality and psychological well-being: Testing a theory of family interdependence among family caregivers and their elders. Res Nurs Health. 2011. 34:103–115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nur.20425.

18. Koenig HG. Concerns about measuring "spirituality" in research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008. 196(5):349–355. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31816ff796.

19. Lee EO. Religion and spirituality as predictors of well-being among Chinese American and Korean American older adults. J Relig Spiritual Aging. 2007. 19(3):77–100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J496v19n03_06.

20. Lee SO, Oh BJ. A correlation study of health promoting behaviors, spiritual well-being and physical function in elderly people. J Korean Gerontol Nurs. 2003. 5(2):127–137.

21. Nygren B, Aléx L, Jonsén E, Gustafson Y, Norberg A, Lundman B.. Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging Ment Health. 2005. 9(4):354–362. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1360500114415.

22. Oak S. Healing and exorcism: Christian encounters with shamanism in early modern Korea. Asian Ethnol. 2010. 69(1):95–128.

23. Paloutzian RF, Ellison CW. Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness, spiritual well-being and the quality of life. Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research, and therapy. 1982. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

24. Reed PG. Religiousness among terminally ill and healthy adults. Res Nurs Health. 1986. 9(1):35–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770090107.

25. Reed PG. Spirituality and well-being in terminally ill hospitalized adults. Res Nurs Health. 1987. 10:335–344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770100507.

26. Reed PG. Self-transcendence and mental health in oldest-old adults. Nurs Res. 1991. 40:5–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199101000-00002.

27. Reed PG. Smith MJ, Liehr PR, editors. Self-transcendence theory. Middle range theory for nursing. 2008. New York: Springer;105–130.

28. Rohani C, Khanjari S, Abedi HA, Oskouie F, Langius-Eklof A. Health index, sense of coherence scale, brief religious coping scale and spiritual perspective scale: Psychometric properties. J Adv Nurs. 2010. 66(12):2796–2806. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05409.x.

29. Sessanna L, Finnell D, Jezewski MA. Spirituality in nursing and health-related literature. J Holist Nurs. 2007. 25(4):252–262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0898010107303890.

30. Thomas JC, Burton M, Quinn Griffin MT, Fitzpatrick JJ. Self-transcendence, spiritual well-being, and spiritual practices of women with breast cancer. J Holist Nurs. 2010. 28:115–122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0898010109358766.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download