Abstract

Purpose

A diagnosis of breast cancer is one of the most traumatic events that threatens a woman's life, but while women adapt to and overcome these threats, they not only experience negative aspects, but also growth. The purpose of this study was to identify the many factors that affect growth, and to provide fundamental information for nursing interventions, which can help the women in their growth.

Methods

The participants in this study were 131 married women patients with breast cancer, who were on medical treatment in one of two university hospitals, in Seoul and Chungnam. Data were collected for posttraumatic growth, self-esteem, cancer coping questionnaire, marital intimacy, and body image. The data were analyzed using the SPSS 19.0 program (IBM).

Figures and Tables

Table 2

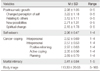

Scores for Posttraumatic Growth, Self-esteem, Cancer-coping, Marital Intimacy and Body Image (N=131)

References

1. Baxter NN, Goodwin PJ, McLeod RS, Dion R, Devins G, Bombardier C. Reliability and validity of the body image after breast cancer questionnaire. Breast J. 2006. 12(3):221–232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00246.x.

2. Cho OH, Yoo YS. Psychosocial adjustment, marital intimacy and family support of post-mastectomy patients. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2009. 9(2):129–135.

3. Choi JH. Posttraumatic growth in cancer patients. 2011. Busan: Catholic University of Pusan;Unpublished master's thesis.

4. Chung SW, Hwang EK, Hwang SW. Marital intimacy and quality of life in women with breast cancer. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2009. 9(2):122–128.

5. Falk Dahl CA, Reinertsen KV, Nesvold IL, Fosså SD, Dahl AA. A study of body image in long-term breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2010. 116(15):3549–3557. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25251.

6. Han IY, Lee IJ. Posttraumatic growth in patients with cancer. Korean J Soc Welf Stud. 2011. 42(2):419–441.

7. Heijer M, Seynaeve C, Vanheusden K, Duivenvoorden HJ, Vos JV, Bartels CCM, et al. The contribution of self-esteem and self-concept in psychological distress in women at risk of hereditary breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2011. 20(11):1170–1175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1824.

8. Jon BJ. Self-esteem: A test of its measurability. Yonsei Nonchong. 1974. 11(1):107–130.

9. Kim HJ, Kwon JH, Kim JN, Lee R, Lee KS. Posttraumatic growth and related factors in breast cancer survivors. Korean J Health Psychol. 2008. 13(3):781–799.

10. Kim JN, Kwon JH, Kim SY, Yoo BH, Hur JW, Sung HJ, et al. Validation of Korean-cancer coping questionnaire (K-CCQ). Korean J Health Psychol. 2004. 9(2):395–414.

11. Kim SH, Lee ES. The stress and adaptation of the spouses of patients with gynecological cancer. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2006. 6(2):162–171.

12. Koo BJ. The influence of resilience, hope, marital intimacy, and family support on quality of life for middle-aged women. J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008. 17(4):421–430.

13. Lee KH. Marriage types classified by wives' perception of marital conflict and intimacy. 1998. Seoul: Seoul University;Unpublished doctoral dissertation.

14. Lee YS. Psychosocial experience in post-mastectomy women. Korean J Soc Welf. 2007. 59(3):99–124.

15. Lepore SJ, Glaser DB, Roberts KJ. On the positive relationbetween received social support and negative affect: A test of the triage and self-esteem threat models in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2008. 17(12):1210–1215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1347.

16. Linley PA, Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. J Trauma Stress. 2004. 17(1):11–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e.

17. Moorey S, Frampton M, Greer S. The cancer coping questionnaire: A self-rating scale for measuring the impact of adjuvant psychological therapy on coping behaviour. Psychooncology. 2003. 12(4):331–344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.646.

18. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN practice guidelines in oncology. 2007. Retrieved 2007. from http://www.nccn.org/index.asp.

19. National Cancer Information Center. Cancer statistics. 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2012. from http://www.cancer.go.kr/ncic/cics_f/01/012/index.html.

20. Posluszny DM, Baum A, Edwards RP, Dew MA. Posttraumatic growth in women one year after diagnosis for gynecologic cancer or benign conditions. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2011. 29(5):561–572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2011.599360.

21. Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. 1965. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University press.

22. Smith BW, Dalen J, Bernard JF, Baumgartner KB. Posttraumatic growth in non-Hispanic White and Hispanic women with cervical cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008. 26(4):91–109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07347330802359768.

23. Song SH, Lee HS, Park JH, Kim KH. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the posttraumatic growth inventory. Korean J Health Psychol. 2009. 14(1):193–214.

24. Statistical Korea. I wish I could have more respect for myself. 2004. Retrieved 2004. from http://kosis.kr/gen_etl/start.jsp?orgId=110&tblId=TX_12019_A332&conn_path=I2&path=NSI.

25. Tedeshi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996. 9(3):455–471. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490090305.

26. Tedeshi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 2004. 15(1):1–18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01.

27. Yang AJ. Mindfulness, positive cancer coping styles and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors-the mediating effect of positive coping style. 2009. Seoul: Ewha Womans University;Unpublished master's thesis.

28. Yoon MO, Park JS. Live spiritual experiences of patients with terminal cancer. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2003. 14(3):445–456.

29. Yu MS, Lee SY. The validation of the Korean version of body image after breast cancer questionnaire. Korean J Play Ther. 2010. 13(1):65–81.

30. Zwahlen D, Hagenbuch N, Carley MI, Jenewein J, Buchi S. Posttraumatic growth in cancer patients and partners-effects of role, gender and the dyad on couples’ posttraumatic growth experience. Psychooncology. 2010. 19:12–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pon.1486.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download