Abstract

Background

Endobronchial ultrasound–guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) is a minimally invasive diagnostic method for mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy. This study aimed to investigate the incidence of fever following EBUS-TBNA.

Methods

A total of 684 patients who underwent EBUS-TBNA from May 2010 to July 2012 at Seoul National University Hospital were retrospectively reviewed. The patients were evaluated for fever by a physician every 6–8 hours during the first 24 hours following EBUS-TBNA. Fever was defined as an increase in axillary body temperature over 37.8℃.

Results

Fever after EBUS-TBNA developed in 110 of 552 patients (20%). The median onset time and duration of fever was 7 hours (range, 0.5–32 hours) after EBUS-TBNA and 7 hours (range, 1–52 hours), respectively, and the median peak body temperature was 38.3℃ (range, 37.8–39.9℃). In most patients, fever subsided within 24 hours; however, six cases (1.1%) developed fever lasting longer than 24 hours. Infectious complications developed in three cases (0.54%) (pneumonia, 2; mediastinal abscess, 1), and all three patients had diabetes mellitus. The number or location of sampled lymph nodes and necrosis of lymph node were not associated with fever after EBUS-TBNA. Multiple logistic regression analysis did not reveal any risk factors for developing fever after EBUS-TBNA.

Endobronchial ultrasound–guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) is a minimally invasive diagnostic method for mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy1. The main use of this technique is in the nodal staging of patients with lung cancer. EBUS-TBNA has also been performed for patients with sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and lymphoma, and in the workup of mediastinal lymphadenopathy of unknown cause. The cumulative sensitivity of EBUS-TBNA in the lymph node staging of lung cancer is 88%–93%23. Hence, EBUS-TBNA has been replacing mediastinoscopy because of its high diagnostic yields and minimal invasiveness.

EBUS-TBNA also has an extremely low complication rate. According to a Japanese nationwide survey, the infectious complication rate of EBUS-TBNA was 0.19%4. A recent study of 3,123 cases undergoing the procedure reported infectious complications in 0.16%5. Serious complications such as mediastinal abscess, pneumomediastinum, empyema, pericarditis, sepsis, and intramural hematoma have been described in case reports678. However, with the increasing use of this method, significant and critical complications may increase.

A total of 684 patients who underwent EBUS-TBNA from May 2010 to July 2012 at Seoul National University Hospital were retrospectively reviewed. Patients were excluded if they had at least one of the following criteria: body temperature >37.5℃ during the 48 hours prior to EBUS-TBNA (n=56), therapeutic bronchoscopy (n=6), conventional bronchoscopy within 24 hours of EBUS-TBNA (n=6), and discharge within 24 hours of EBUS-TBNA (n=64). Finally, 552 patients were included in the analysis.

All EBUS-TBNA was performed using a real-time linear probe (BF-UC260F-OL8 and BF-UC260FW; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). We used a 22-guage needle (NA-201SX-4022; Olympus) for transbronchial aspiration, and conventional flexible bronchoscopy was performed before the EBUS-TBNA examination. If the patient had already taken the bronchoscopy examination, the EBUS-TBNA was conducted immediately after. We used a flexible bronchoscope with a 5.9 mm diameter (model BF-200 or BF-1T240; Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan). Of 552 patients, 532 (96.4%) underwent conventional bronchoscopy before the EBUS-TBNA examination. EBUS-TBNA was performed with the patient under moderate sedation using fentanyl and midazolam, as well as local anesthesia using lidocaine.

The patients were evaluated for fever by a physician every 6–8 hours during the first 24 hours following EBUS-TBNA. Fever was defined as an increase in axillary body temperature over 37.8℃.

White blood cells (WBC) and neutrophil counts were obtained before EBUS-TBNA in and at the time of fever. When fever developed after EBUS-TBNA, two sets of blood cultures (both aerobic and anaerobic) were performed.

A chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables, and a t test was used to compare continuous variables. The odds ratios for the risk of fever following EBUS-TBNA were analyzed using a multivariate logistic regression model, including age, sex, any variables with a p<0.20, and prior immunosuppressive or antibiotic therapy that could impact fever after EBUS-TBNA. A p<0.05 was considered to indicate significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

The records of a total of 552 patients who underwent EBUS-TBNA were reviewed. The median age was 66 years (range, 22–87 years), and 387 patients were male (70.1%). The baseline clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. The indications of EBUS-TBNA were for the staging of lung cancer in 386 cases, diagnosis of cancer (lung cancer in 27 cases, and others in 68 cases, suspected of sarcoidosis in 19 cases, tuberculosis in seven cases, and mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy in 45 cases). Fever after EBUS-TBNA developed in 110 of 552 patients (20%).

One hundred twenty one patients (21.9%) underwent bronchoscopic procedure including biopsy, washing and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). There were no differences in abnormal bronchoscopic findings such as bronchial obstruction or narrowing and bronchoscopic procedures between the fever and non-fever group.

The total number of sampled lymph nodes or lung masses was 2.3±0.9. The most frequently punctured lymph node was the lower paratracheal lymph node in 472 cases (85.5%), followed by the subcarinal lymph node in 350 cases (63.4%). There were no differences in the number or location of sampled lymph nodes and necrosis of lymph node on computed tomography (CT) between groups (Table 2). When we evaluated factors for developing fever after EBUS-TBNA using a multivariate model including age, smoking history, prior immunosuppressant therapy, prior antibiotic therapy, bronchial obstruction or narrowing, number of sampled lymph nodes or mass and diagnosis of tuberculosis, no risk factors for fever following EBUS-TBNA were observed (Table 3).

The median onset and duration of fever after EBUS-TBNA was 7 hours (range, 0.5–32 hours) and 7 hours (range, 1–52 hours), respectively, and the median peak body temperature was 38.3℃ (range, 37.8℃–39.9℃). Of 110 febrile patients, 43 patients (39%) received antibiotic treatment due to fever after EBUS-TBNA. Fever in most patients (94.5%) resolved within 24 hours. Accompanying symptoms were chill in 46.4%, febrile sense in 30.9%, general ache in 10.9%, and dyspnea in 5.5% patients. Thirty-four patients (30.4%) had no symptoms.

Blood culture samples at the time of fever were taken in 56 (50.9%) patients and positive in two (1.8%). Streptococcus hominis was identified in only a single positive culture of the patients and is part of the normal skin flora thereby able to contaminate blood cultures. None of the bacteraemic patients showed clinical features suggestive of infection. Therefore, no true bacteremia was found. Peripheral WBC and neutrophil counts increased significantly at the time of fever than the pre–EBUS-TBNA values (n=57) (Figure 1).

Six of 110 febrile patients developed prolonged fever lasting longer than 24 hours, and pneumonia developed in two of the six patients. Three of six patients (50%) with prolonged fever had diabetes mellitus and 12 of 104 patients (11.5%) with fever that subsided within 24 hours had diabetes mellitus. Diabetes mellitus was more common in patients with prolonged fever than in patients with non-prolonged fever (p=0.032). Both patients who developed pneumonia had diabetes.

We experienced one case of mediastinal abscess developing after EBUS-TBNA. A 69-year-old female patient with underlying diabetes mellitus underwent EBUS-TBNA for diagnosis of mediastinal lymphadenopathy, but no specific diagnosis was obtained. She developed fever 3 days after the procedure that continued for 7 days, at which time she was diagnosed with mediastinal abscess. After 7 days of antibiotic therapy, the patient became afebrile. The patient was successfully treated with antibiotics for 6 weeks.

Our study showed that incidence of fever following EBUS-TBNA was 20%. In most patients, fever develops during the day after procedure, and subsides within a day. Six cases (1.1%) developed fever lasting longer than 24 hours and infectious complications developed in three cases (0.54%). To the best of our knowledge, only two studies have reported fever after EBUS-TBNA. In a Japanese nationwide survey of 7,345 cases of EBUS-TBNA, the fever and infectious complications developed in four cases (0.05%) and 14 cases (0.19%), respectively4. The other study evaluated only fever lasting longer than 24 hours. The study reported that one case (0.03%) developed fever lasting longer than 24 hours and four cases (0.13%) developed infectious complications out of a total of 3,123 cases5.

However, there was not detailed information regarding the definition, onset or duration of fever because these studies evaluated incidence of fever through a questionnaire survey. In our institution, all patients were admitted to conduct EBUS-TBNA and evaluated for fever every 6–8 hours following EBUS-TBNA. We also excluded patients who discharged within 24 hours of EBUS-TBNA. The inconsistent results may reflect differences between patients included and excluded, definitions of fever, methods for evaluation of fever and interval and duration of measuring body temperature. Therefore, the fever rate of other studies might be underestimated. Eapen et al.14 studied prospectively to investigate the incidence of and risk factors for complications in patients undergoing EBUS-TBNA and reported that complications occurred in 19 (1.44%) of total 1,317 patients. However, they did not evaluate fever after EBUS-TBNA. Overall, this is the first report to thoroughly investigate the incidence of fever following EBUS-TBNA.

The rate of fever following conventional flexible bronchoscopy varies according to different reports, ranging from 5% to 16%91011. Fever after bronchoscopy usually begins a few hours after the procedure, and subsides within 24 hours of onset. These clinical courses of fever after bronchoscopy are consistent with the results of the present study. According to previous reports91516, fever following bronchoscopy is associated with old age, abnormal bronchoscopic findings, biopsy, BAL, amount of saline solution or topical anesthetic, duration of the procedure, severity of bleeding, and a final diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. However, in the present study, there appeared to be no relationship between fever and bronchoscopic procedures such as washing and biopsy, abnormal bronchoscopic findings, number of sampled lymph nodes or necrosis of lymph nodes on CT. The exact cause of fever following EBUS-TBNA remains unclear.

One possible cause of fever after EBUS-TBNA is transient bacteremia because of the inoculation of oropharyngeal bacteria through transbronchial aspiration. Steinfort et al.17 prospectively studied the rate of bacteremia in 43 patients undergoing EBUB-TBNA. Bacteremia was observed in three patients (7%), and all bacterial organisms were typical oropharyngeal flora. However, the three bacteremic patients did not have clinical features suggestive of infection. In a study to examine the incidence of fever and bacteremia in 50 procedures for conventional TBNA, fever occurred in 10% and no bacteremia was found13. In our study, two patients (1.8%) had positive blood culture. Identified organism was normal flora of skin and there was no true bacteremia. These results suggest that fever after EBUS-TBNA is not related to bacteremia.

Several studies have suggested that the cause of fever after bronchoscopy is a systemic inflammatory response. We showed significant increases in the total leukocyte and neutrophil counts in the blood at the time of fever relative to the pre–EBUS-TBNA values. These results were consistent with other study9. Krause et al.16 suggested that fever develops after bronchoscopy because of the release of inflammatory cytokines due to their release into the blood stream caused by the alveolar cells after the instillation of fluid. Fever after EBUS-TBNA may be a manifestation of systemic inflammatory response due to physical irritations such as suctioning and TBNA, as well as to fluid instillation.

In the present study, infectious complications developed in three cases (0.54%), with pneumonia observed in two cases (0.36%) and mediastinal abscess in one (0.18%). A Japanese survey reported that the rate of infectious complication was 0.19% (mediastinitis, 0.09%; pneumonia, 0.05%; pericarditis, 0.01%; cyst infection, 0.01%; sepsis, 0.01%)4. Similarly, a recent study in Turkey showed an infectious complication rate of 0.16% (fever lasting longer that 24 hours, 0.03%; infection of bronchogenic cyst, 0.03%; mediastinal abscess, 0.03%; pericarditis, 0.03%; pneumomediastinitis with empyema, 0.03%)5. Several cases with infectious complications caused by EBUS-TBNA have been reported678181920212223, and we reviewed fifteen of these. Most patients usually developed fever at 4–10 days after EBUS-TBNA. Similarly, in our study, one case of mediastinal abscess developed fever 3 days after the procedure. Although risk factors for infective complications after EBUS-TBNA have not been determined, they may include biopsy of necrotic structures compromising bacterial inoculation clearance mechanisms, operator inexperience and immunocompromised state due to underlying diseases such as diabetes mellitus and end stage renal disease622. In our study, all three patients with infectious complications had diabetes mellitus.

It is important to note that this study had several limitations. Specifically, there was no long term follow-up of any cases for the assessment of fever and infectious complications after EBUS-TBNA because of the retrospective study design. Additionally, 43 patients of 110 febrile patients (39%) received antibiotic treatment due to fever after EBUS-TBNA. As a result, our study could underestimate the incidence of fever and infectious complications after EBUS-TBNA. Finally, we excluded 64 patients who discharged within 24 hours after the EBUS-TBNA because they couldn’t be evaluated fever and thus our study had the potential for a selection bias.

In conclusion, fever is relatively common after EBUS-TBNA, but is transient in most patients. However, clinicians should be aware of the possibility of infectious complications among patients with diabetes mellitus.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

Changes in peripheral blood white blood cell (WBC) and neutrophil counts before endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)–guided transbronchial needle aspiration and at the time of fever in the fever group (n=57). *p=0.030. †p<0.001.

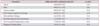

Table 1

Comparison of baseline characteristics and bronchoscopic findings and procedures between fever and non-fever group

Table 2

Comparisons of characteristics of lymph nodes, final diagnosis, and radiologic findings between fever and nonfever group

Table 3

Predictors of fever after EBUS-TBNA (multivariable analysis)

References

1. Yasufuku K, Chiyo M, Sekine Y, Chhajed PN, Shibuya K, Iizasa T, et al. Real-time endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Chest. 2004; 126:122–128.

2. Gu P, Zhao YZ, Jiang LY, Zhang W, Xin Y, Han BH. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for staging of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2009; 45:1389–1396.

3. Adams K, Shah PL, Edmonds L, Lim E. Test performance of endobronchial ultrasound and transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy for mediastinal staging in patients with lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2009; 64:757–762.

4. Asano F, Aoe M, Ohsaki Y, Okada Y, Sasada S, Sato S, et al. Complications associated with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a nationwide survey by the Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy. Respir Res. 2013; 14:50.

5. Caglayan B, Yilmaz A, Bilaceroglu S, Comert SS, Demirci NY, Salepci B. Complications of convex-probe endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a multi-center retrospective study. Respir Care. 2016; 61:243–248.

6. Leong SC, Marshall HM, Bint M, Yang IA, Bowman RV, Fong KM. Mediastinal abscess after endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a case report and literature review. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2013; 20:338–341.

7. Haas AR. Infectious complications from full extension endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration. Eur Respir J. 2009; 33:935–938.

8. Lee HY, Kim J, Jo YS, Park YS. Bacterial pericarditis as a fatal complication after endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015; 48:630–632.

9. Um SW, Choi CM, Lee CT, Kim YW, Han SK, Shim YS, et al. Prospective analysis of clinical characteristics and risk factors of postbronchoscopy fever. Chest. 2004; 125:945–952.

10. Sharif-Kashani B, Shahabi P, Behzadnia N, Mohammad-Taheri Z, Mansouri D, Masjedi MR, et al. Incidence of fever and bacteriemia following flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy: a prospective study. Acta Med Iran. 2010; 48:385–388.

11. Kanemoto K, Satoh H, Ishikawa H, Ishikawa S, Ohtsuka M, Sekizawa K. Prospective study of fever and pneumonia after flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006; 54:827–830.

12. Darjani HR, Kiani A, Bakhtiar M, Sheikhi N. Diagnostic yield of transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) for cases with intra-thoracic lymphadenopathies. Tanaffos. 2011; 10:43–48.

13. Witte MC, Opal SM, Gilbert JG, Pluss JL, Thomas DA, Olsen JD, et al. Incidence of fever and bacteremia following transbronchial needle aspiration. Chest. 1986; 89:85–87.

14. Eapen GA, Shah AM, Lei X, Jimenez CA, Morice RC, Yarmus L, et al. Complications, consequences, and practice patterns of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: results of the AQuIRE registry. Chest. 2013; 143:1044–1053.

15. Pereira W, Kovnat DM, Khan MA, Iacovino JR, Spivack ML, Snider GL. Fever and pneumonia after flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1975; 112:59–64.

16. Krause A, Hohberg B, Heine F, John M, Burmester GR, Witt C. Cytokines derived from alveolar macrophages induce fever after bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997; 155:1793–1797.

17. Steinfort DP, Johnson DF, Irving LB. Incidence of bacteraemia following endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Eur Respir J. 2010; 36:28–32.

18. Oguri T, Imai N, Imaizumi K, Elshazley M, Hashimoto I, Hashimoto N, et al. Febrile complications after endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for intrapulmonary mass lesions of lung cancer: a series of 3 cases. Respir Investig. 2012; 50:162–165.

19. Huang CT, Chen CY, Ho CC, Yu CJ. A rare constellation of empyema, lung abscess, and mediastinal abscess as a complication of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011; 40:264–265.

20. Kouskov OS, Almeida FA, Eapen GA, Uzbeck M, Deffebach M. Mediastinal infection after ultrasound-guided needle aspiration. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2010; 17:338–341.

21. Moffatt-Bruce SD, Ross P Jr. Mediastinal abscess after endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration: a case report. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010; 5:33.

22. Ishimoto H, Yatera K, Uchimura K, Oda K, Takenaka M, Kawanami T, et al. A serious mediastinum abscess induced by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA): a case report and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2015; 54:2647–2650.

23. Fukunaga K, Kawashima S, Seto R, Nakagawa H, Yamaguchi M, Nakano Y. Mediastinitis and pericarditis after endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Respirol Case Rep. 2015; 3:16–18.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download