Abstract

Since 2015, the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) has performed annual qualitative assessments of asthma management provided by all medical institutions that care for asthma patients in Korea. According to the third report of qualitative assessment of asthma management in 2017, the assessment appears to have contributed to improving the quality of asthma care provided by medical institutions, especially primary clinics. However, there is still a gap between the ideal goals of asthma management and actual health care policies/regulations in real clinical settings, which leads to the state of standstill with respect to the quality of asthma management despite considerable efforts such as the qualitative assessment of asthma management by national agencies such as the HIRA. At this point, a harmonized approach is needed to raise the level of asthma management among several components including medical policies, efforts of academic associations such as education and distribution of the guideline for management, and reliable financial support by the government.

In March 2017, Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) has released the results of qualitative assessment for asthma management provided by all medical institutions that care for asthma patients in Korea1. In fact, this is third report since HIRA released its first report in January 2015. The purposes of the quality assessment are to improve the quality of asthma management provided by medical institutions, prevent the progression/exacerbation, and inform the patients of the necessity for the continuous asthma management. This will improve public health status and lead to appropriate expenditure on health care costs and they are the ultimate goals of the qualitative assessment of asthma management.

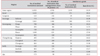

The third qualitative assessment of asthma management was conducted using the data collected by HIRA from July 2015 to June 2016. They analyzed all patients recorded with diagnostic codes J45 and J46 in HIRA's database according to 10th International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). In the qualitative assessment of asthma management, seven items were analyzed as follows: (1) performance rate of pulmonary function test, (2) percentage of visits to same medical institution for asthma management, (3) prescription rate of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), (4) prescription rate of anti-inflammatory controllers for asthma such as leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs) and ICS, (5) prescription rate of long acting β2-agonists (LABA) without ICS, (6) prescription rate of short acting β2-agonists without ICS, and (7) prescription rate of oral corticosteroids (OCS) without ICS. Among these seven items, four items numbered from 1 to 4 were sub-categorized as mandatory items. The results revealed that the total number of asthmatic patients was 776,882, which was lower than the previous two reports: 831,613 in first report and 818,771 in second report. Most patients (79.8%) have received asthma treatment from their primary care physician in private clinics. Primary care physicians were general physicians, internists, and respiratory/allergy specialists. The primary private clinics accounted for about 88.1% of all medical institutions providing asthma management in Korea. In addition, the minority of asthmatic patients received the medical services at the general hospitals (7.2%), the geriatric hospitals (2.2%), and tertiary general hospitals (0.3%). Results of assessment for the seven items for asthma management are summarized in Table 1. In brief, the mean performance rate of pulmonary function tests was 28.3% for all medical institutions and 20.1% for primary private clinics. The rate of visits to the same medical institution for asthma management was 72.0% in all medical institutions. The prescription rate for ICS or anti-inflammatory controllers (i.e., ICS or LTRAs) was 30.6% or 63.7% for total medical institutions, respectively. Based on the results of the assessment, HIRA classified the medical institutions as two grades, satisfactory and unsatisfactory grades. When a medical institution earned a score above the median value of four mandatory items, the institution was considered to be satisfactory grade. According to the results of this assessment, the medical institutions valued in the satisfactory grade accounted for only 16.19% of clinics where more than ten asthma patients visit per year (Table 2). The list of medical institutions of satisfactory grade only was publicly announced by HIRA through official announcements, press, and websites.

This quality assessment for asthma management has been performed in two aspects, correct diagnosis and optimal treatment. The goal of this HIRA's project is to encourage physicians and health care workers who treat asthmatic patients to follow the international and Korean guideline for asthma management in their clinical settings. Particularly, in terms of diagnosis, physicians are advised to use pulmonary function tests, including spirometry with bronchodilator response test or bronchial provocation test rather than relying solely on the history taking and physical examinations. The test is helpful to identify the presence of airflow obstruction and other pulmonary disorders such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disorders, the bronchodilator response, and the degree of hyperresponsiveness at the time of diagnosis and the progress of the disease. On the other hand, the use of anti-inflammatory medicines, especially ICS is emphasized to improve the quality of treatment, which has been considered first-line maintenance therapy2. As shown in the results of this report, performance rate of pulmonary function test is low at 28.3% and in cases of primary private clinics the rate is much lower at 20.1%. Given that most of the institutions evaluated in this assessment are primary clinics which account for almost 80%, this low level of performance rate of pulmonary function test seems to reflect the results of primary clinics. Interestingly, the prescription rate of ICS was very similar to the performance rate of pulmonary function test and also very low at 28.3% and 30.6% in total medical institutions and 20.1% and 20.1% in primary clinics, respectively. Whereas, the prescription of anti-inflammatory controllers including LTRAs was relatively high, which suggests the physicians and/or patients prefer to use oral medications than inhaled formulations. In the United States, the rate of ICS in anti-inflammatory medication use represents a major portion at 72.5%3. In Europe, about 43% of the population has used ICS for asthma4. Considering these findings, the ICS prescription rate in Korea is much lower seriously. In addition, the rates in two important items which are performance of pulmonary function test and the use of ICS are still as low as about 30%, although the trend has been increased for three years (Table 3). These observations suggest that these two items seem to be influenced by one another and by similar other factors.

In fact, considerable primary clinics, even steered by internists have no facilities for pulmonary function test or even if they are equipped with the facilities, physicians do not use it frequently in Korea, because the test is required of relatively more time and the special technicians for the performance. At present, in real practice, primary physicians have many difficulties to spend enough time managing each patient due to several limitations of Korean health care system such as medical insurance premium regulations and some policies. Moreover, the cost of inhaled formulations is higher than that of oral medications. Additionally, with the use of ICS, physicians should spend more time and efforts explaining the patients how to properly use the inhaler and checking for proper use on subsequent visits. Without the compensation for these efforts, the physicians prefer to prescribe oral medications. In this point, there is a slight discrepancy between the ideal goals of asthma management and actual health care policies/regulations of national medical insurance. This quality assessment of asthma management encourages the early and active use of ICS to prevent the diseases progression and acute exacerbation, while current National Health Insurance regulations strictly restrict the use of expensive medications such as ICS. This irony needs to be adequately corrected by policies for better management of asthma.

Of course, to improve the quality of asthma management, it is most important that physicians and patients recognize the need for pulmonary function testing and the use of ICS in asthma management. Actually, the patients often refuse to undergo additional medical examinations including pulmonary function test despite the physicians' recommendation. Doctors also do not like to perform the tests due to some inconvenience. In terms of this view, the correct knowledge and updated information for asthma as well as the more simple methods to evaluate pulmonary function such as peak flow monitoring should be shared with the physicians and patients though public relations activity, distribution of management guideline, education for health care workers, the general publics, students, and even kids. Regular evaluation/survey for the awareness and the related performance by patients and physicians is also needed. However, delivery of the knowledge and up-to-date information only to the public and physicians without any political supports seems to have many limitations to overcome practical difficulties of proper asthma management. In the report on third qualitative assessment of asthma management, the prescription rate of OCS without ICS was still high at 28.2% and the rate was getting much higher in primary clinics (33.1%). The first quality assessment defined the sole prescription rate of OCS without ICS as the prescription for the duration longer than 2 weeks. The third assessment made a change to the definition by removing the terms concerning the duration longer than 2 weeks. When the new definition is applied to the results from the first assessment, adjusted prescription rate of OCS without ICS in the first assessment is 30.36% (Table 3). The results seem to be derived from the reality that although the physicians are aware of the need for antiinflammatory controllers in asthma treatment, they still prefer to prescribe oral medications such as OCS rather than ICS because there are many hurdles left by the health care systemic dissonance in real clinical settings.

A good example for the induction of actual behavioral changes in asthma management of patients and physicians is the Finland's 10 year-national program lasting from 1994 to 2004 to improve asthma care and limit the projected increases in costs56. The program was run by the Finnish Lung Health Association and supported financially by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health who gave their political commitment to the program. In the program, measures to achieve the goals were as follows: (1) early diagnosis and active treatment, (2) guided self-management as the primary form of treatment, (3) reduction in respiratory irritants such as smoking and environmental tobacco smoke, (4) implementation of patient education and rehabilitation combined with normal treatment, planned individually and timed appropriately, (5) increase in knowledge about asthma in key groups, and (6) promotion of scientific research. According to the report on the program, the medical cost per patient for asthma management has decreased 36%. There are also several indicators that show significant decreases in the proportion of patients with severe complications such as hospitalization days, disability pensions, and allowances for days off work6. As for the use of ICS, in 1987 a nationwide health survey showed that only one third of Finnish asthma patients used ICS67. Very encouragingly, both in 2001 and 2004, over 85% of patients purchasing asthma drugs from pharmacies used ICS daily in Finland68. This successful program is also addressing that this kind of program cannot be effective without organized follow up and feedback, but even these are not enough and that financial resources are necessary to start up and monitor the program but the two key words for success are “motivate” and “organize”6. Therefore, benchmarking successful models such as the Finnish national project is one of better approaches to improve asthma management and it should be tailored to the practices in Korea.

Lastly, there is some controversy whether efforts to increase the prescription rate of single ICS are sufficient to manage asthmatic patients. In fact, many asthmatics require a combined inhalation formulation of ICS and LABA for their controlled state of asthma linked to prevention of acute exacerbation. It is thought that the current assessment for ICS use include the use of combined formulation of ICS and LABA; however, given that the medical insurance premium regulation for the use of combined inhalation formulation of ICS and LABA is stricter than single ICS in primary clinics, the prescription rate of the combined ICS and LABA is expected to be much lower than single ICS. Therefore, in a long-term view, the use of combined inhalation formulation including ICS and LABA as well as single ICS should be recommended and assessed by national policies, academic programs, and quality assessment cooperatively for the ultimate goals of asthma management.

In conclusion, it is clear that HIRA's quality assessment for asthma management, one of national agencies, is valuable to improve the level of asthma care provided by medical institutions, especially primary clinics. It is also very encouraging that asthma is accepted as a major chronic disorder that needs to be assessed and monitored by public authorities such as HIRA. However, the current assessment tools are insufficient to induce a real impact on actual behavioral changes, as shown in the results to date of the quality assessments that show little change in each item of quality assessment over the past 3 years. In order to achieve the actual effects of these quality assessments for asthma management, it seems that the harmonized approach is required among several components including medical policies, efforts of academic associations such as education and distribution of guideline for management, and reliable financial support by the government.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Summary of results of the third report of quality assessment of asthma management by the HIRA

Table 2

Regional status of the proportion of medical institutions given a satisfactory grade in Korea

Table 3

Changes in outcomes of quality assessment of asthma management by the HIRA

*The value in bracket indicates the rate in primary clinics only. †The adjusted prescription rate of OCS without ICS in the first and second report based on the new definition form the third quality.

HIRA: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; OCS: oral corticosteroids.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea; Grant HI12C1786 and Grant HI16C0062 and by the fund of Biomedical Research Institute, Chonbuk National University Hospital.

We appreciate all the efforts of the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service.

References

1. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service [Internet]. Wonju: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service;2017. cited 2017 May 16. Available from: http://www.hira.or.kr.

2. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention [Internet]. Bethesda: Global Initiative for Asthma;2017. updated 2017. cited 2017 May 16. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org.

3. Adams RJ, Fuhlbrigge A, Guilbert T, Lozano P, Martinez F. Inadequate use of asthma medication in the United States: results of the asthma in America national population survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002; 110:58–64.

4. Cazzoletti L, Marcon A, Janson C, Corsico A, Jarvis D, Pin I, et al. Asthma control in Europe: a real-world evaluation based on an international population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007; 120:1360–1367.

5. Haahtela T, Laitinen LA. Asthma programme in Finland 1994-2004. Report of a Working Group. Clin Exp Allergy. 1996; 26:Suppl 1. 1–24.

6. Haahtela T, Tuomisto LE, Pietinalho A, Klaukka T, Erhola M, Kaila M, et al. A 10 year asthma programme in Finland: major change for the better. Thorax. 2006; 61:663–670.

7. Peura S, Martikainen J, Klaukka T. Use and costs of asthma medication in 1980s. Publication M: 72. Helsinki: Social Insurance Institution;1990.

8. Klaukka T, Hirvonen A, Karhula K, Peura S. Good and bad news from asthma. Asthma barometer 2004. Suom Laakaril. 2004; 42:4002–4004.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download