Abstract

Pulmonary strongyloidiasis is an uncommon presentation of Strongyloides infection, usually seen in immunocompromised hosts. The manifestations are similar to that of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Therefore, the diagnosis of pulmonary strongyloidiasis could be challenging in a COPD patient, unless a high index of suspicion is maintained. Here, we present a case of Strongyloides hyperinfection in a COPD patient mimicking acute exacerbation, who was on chronic steroid therapy.

Exacerbation is an inevitable reality in the natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Most exacerbations are consequences of infection with viruses or bacteria1. Inhaled bronchodilator, antibiotics, corticosteroid with or without non-invasive ventilation remain the mainstay of management for COPD exacerbation. Inhaled long-acting bronchodilators are the preferred therapy and oral corticosteroids has no role in management of stable disease2. Long-term steroid therapy can lead to a state of immunosuppression and potentially increases the risk of opportunistic infections in COPD patients. Strongyloides stercoralis is a human intestinal nematode endemic in tropical and subtropical countries including India. Most infections remain asymptomatic; however, severe strongyloidiasis such as hyperinfection and disseminated disease can occur in immunocompromised hosts 345. We report a case of Strongyloides hyperinfection in a COPD patient mimicking acute exacerbation who was on oral corticosteroids for long duration.

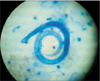

A 62-year-old man, previously diagnosed with COPD presented with increasing breathlessness, cough productive of mucoid sputum for 2 months and bilateral pedal edema for 1 month. He was a farmer and former smoker with history of 35 pack-years of smoking. He had no diabetes but was known to have hypertension of 10 years duration. His regular medication included amlodipine and telmisartan and he used to take oral betamethasone (over the counter basis) almost daily with intermittent parenteral dexamethasone for last 3 years for controlling COPD symptoms. Physical examination revealed an average built man with pulse rate 126 per minute, blood pressure 168/110 mm Hg, respiratory rate 30 breaths per minute, and room air oxygen saturation of 92% by pulse oximetry. General examination showed features of chronic steroid use like facial puffiness, nape of neck swelling, and bilateral pitting pedal edema. He was afebrile and fully conscious without any neurological deficit. Chest auscultation revealed bilateral diminished air entry with wheezes and crackles. Examination of other systems was essentially normal. Hemogram showed a hemoglobin concentration of 12.2 g/dL, white blood cells counts 15,090/mm3 with differentials of polymorphs 92%, lymphocytes 7%, monocytes 1%, and platelets count of 2.91 Lac/mm3. Renal function was impaired with raised blood urea (65 mg/dL) and creatinine (1.7 mg/dL). Serum electrolytes and liver function test were normal. Chest radiograph showed bilateral lung hyperinflation with prominent vascular markings (Figure 1). Suspecting acute exacerbation of COPD, treatment with parenteral amoxicillin-clavulunate along with intravenous hydrocortisone, diuretic, nebulized salbutamol, and oral theophylline was started. Expectorated sputum was subjected to Gram stain, acid fast staining, fungal mount and routine culture. Sputum culture grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa sensitive to ciprofloxacin. Surprisingly, Zeihl-Neilsen stain of sputum revealed larvae resembling S. stercoralis (Figure 2). Subsequently, actively motile larvae of S. stercoralis were identified in successive stool samples examined in wet mount preparation (Figure 3, Video clip 1). Strongyloides hyperinfection was diagnosed and oral ivermectin was added to the treatment regimen immediately. Our case did not manifest peripheral blood eosinophilia or increased sputum eosinophil count. High resolution computed tomography scan of lungs showed only diffuse emphysematous changes. Flexible bronchoscopy revealed inflamed airway mucosa; however, bronchoalveolar lavage microscopy was noncontributory for Strongyloides . Blood culture was reported sterile. Serology for human immunodeficiency virus was negative. Serum immunoglobulin E was not measured. Further systemic evaluation established evidence of retinopathy and nephropathy related to long-standing hypertension. Echocardiography showed concentric left ventricular hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, mild pulmonary artery hypertension, and tricuspid regurgitation with normal (ejection fraction 55.8%) left ventricular systolic function. The present exacerbation of COPD was attributed to Strongyloides hyperinfection. Hydrocortisone was discontinued on second day, antibiotic was changed to ciprofloxacin and ivermectin 12 mg daily (200 µg/kg) single dose was continued for 14 days. Patient improved symptomatically and he was discharged after a week with inhaled bronchodilator and oral theophylline for long-term control of COPD. Spirometry performed during follow-up after 2 weeks showed obstruction with poor bronchodilator reversibility (post bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1] 53%, forced vital capacity [FVC] 62%, and post bronchodilator FEV1/FVC 82% of predicted) and repeat examinations of stool and sputum were negative for Strongyloides.

Strongyloidiasis is caused by the female nematode S. stercoralis. The life cycle of S. stercoralis consists of two larval forms: one is free-living rhabditiform larvae in the outside environment (soil) and the other is a parasitic filariform larvae within the host. The infective filariform larvae enters the human host through the skin, gain access to the circulation and reach the gastrointestinal tract via lungs where it mature to non-infective rhabditiform larvae those are excreted in the stool, thus completing the life cycle. Some of these rhabditiform larvae transform to the filariform larvae in the gut and penetrates through the bowel mucosa or perianal skin to reach the lung without being excreted in the stool. This ability of Strongyloides to recycle itself within the human host without needing the external environment is known as autoinfection. Because of autoinfection, the parasites can persist in the human body for decades or for the rest of the host life even after the host ceases to live in an endemic area346. Most Strongyloides infections manifest as asymptomatic peripheral blood eosinophilia that varies from 350/µL to 450/µL7. Hyperinfection syndrome is an accelerated autoinfection where there is increased larval burden that commonly occurs in immunocompromised hosts but can be seen in immunocompetent individuals as well6. Disseminated disease is defined as the systemic migration of larvae beyond the traditional gut-lung route. The common sites of dissemination are liver, brain, heart, and urinary tract34. Patients may present with severe manifestations like shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, respiratory failure, bacterial or aseptic meningitis, and renal failure3.

In hyperinfection, exacerbation of gastrointestinal and pulmonary symptoms is seen and the detection of increased number of larvae in stool and sputum is the hallmark of hyperinfection. Patients may present with increasing cough, dyspnea, or wheezing mimicking exacerbation of COPD78, acute respiratory distress syndrome9, abdominal catastrophe and gram-negative septicemia10. Corticosteroids use has been most commonly associated with the progression of chronic infection to hyperinfection and a short course of a week or two may be sufficient to develop hyperinfection. The other patients at risk for hyperinfection are those receiving chemotherapy, and those with hematologic malignancy, kidney transplants, bone marrow transplants, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 infection, and hypogammaglobulinemia 3510. Besides the large parasite burden and systemic dissemination, gram-negative bacteraemia is frequently associated with hyperinfection or disseminated disease. This occurs due to translocation of enteric bacilli carried on the larval surface during its migration in to the circulation. Therefore, common blood culture isolates are Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas, and Enterococcus faecalis310. Radiologically, pulmonary strongyloidiasis manifests as diffuse or focal interstitial shadow, alveolar opacity, nodular lesions, and even cavitation11. The diagnosis is usually established by identification of larvae in stool microscopy and sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid by Gram, Papanicolaou, or acid-fast stains. The larvae have also been demonstrated in bronchial brushings, lung biopsies, pleural fluid, gastric or duodenal mucosal biopsies by microscopic examination3. The sensitivity of stool microscopy in detecting Strongyloides larvae varies from 75.9% in one sample to 92% when three samples are examined4. Serological test for demonstration of antibodies is also a useful and sensitive test, particularly for chronic strongyloidiasis; however, the same is not reliable in hyperinfection syndrome as it may be negative due to immunosuppression4.

Unlike, chronic strongyloidiasis, peripheral eosinophilia is strikingly uncommon in hyperinfection and disseminated disease56. Therefore, absence of peripheral eosinophilia should not be considered as criteria for exclusion of Strongyloides hyperinfection. Indeed, lack of peripheral eosinophilia has been linked to more severe infection and increased fatality in hyperinfection syndrome. Peripheral eosinophilia is an indirect marker of immune response in Strongyloides infection. Corticosteroids therapy affects the eosinophilic defence and predisposes for hyperinfection and may also have a direct stimulatory effect on the parasite accelerating larval burden10.

Differentiating pulmonary strongyloidiasis from acute exacerbation of COPD could be difficult as the manifestations are similar. Therefore, a high index of clinical suspicion is crucial for the early diagnosis of hyperinfection syndrome. Moreover, patients may not complain of abdominal symptoms as they may perceive it irrelevant at a time of acute respiratory distress or have accepted it as a part of their life owing to long-standing duration. Therefore, unless clinicians proactively enquire for abdominal symptoms, this may be missed leading to delay in diagnosis. At times abdominal symptoms may be erroneously treated as hyperacidity or gastroesophageal reflux disease. Furthermore, peripheral eosinophilia, if present in a COPD patient presenting with hyperinfection syndrome may be misleading as the same may be considered as a surrogate for eosinophilic airway inflammation and patients may be prescribed corticosteroid liberally that could be perpetual for the hyperinfection. Mostly, the diagnosis is unsuspected in such patients and comes as surprise by chance detection of larvae in respiratory samples (sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage) subjected for routine microbiological tests that leads to further examination of stool and other body fluids to establish the diagnosis. Fortunately, Strongyloides larvae were identified in first sputum sample of our patient stained for acid-fast bacilli and subsequent stool examination demonstrated numerous larvae. Identification of larvae in stool and sputum, growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in sputum culture, absence of peripheral eosinophilia, and remarkable response to ivermectin reaffirmed our diagnosis of hyperinfection syndrome. The negative bronchoalveolar lavage result may be due to delay in sampling (two days after starting ivermectin) or one-time nature of sampling. He might have acquired the infection easily being a farmer and prolong use of corticosteroid resulted in hyperinfection syndrome.

In general, there is a low prevalence of Strongyloides infections in Korea as only few cases have been reported. Majority of reported cases belong to gastrointestinal strongyloidiasis 121314. A case of gastrointestinal hyperinfection with Strongyloides was confirmed by examination of gastric biopsy and gastroduodenal aspirate in an elderly lady receiving corticosteroid for arthritis15. In the year 2005, Kim et al.16 reported the first case of a fatal pulmonary strongyloidiasis by autoinfective filariform larvae in an asthmatic patient receiving chronic steroid therapy. The diagnosis was established by demonstration of larvae in expectorated sputum sample during cytological examination by Papanicolaou staining whereas Giemsa and acid-fast staining were negative for the parasite16. Our case was diagnosed by identification of larvae in acid-fast staining of sputum. Recently another case of Strongyloides hyperinfection presenting with alveolar hemorrhage has been reported in an elderly man receiving chemotherapy for small cell carcinoma of lung17.

Ivermectin is the treatment of choice for Strongyloides infection. Oral ivermectin at 200 µg/kg for 2 days remains the standard of treatment for uncomplicated infections. Alternatively, albendazole at 400 mg twice a day for 3–7 days can be used but found to be slightly less effective than ivermectin in uncomplicated strongyloidiasis4. What duration of treatment constitutes adequate therapy for hyperinfection and disseminated disease is not clearly defined. Presently, oral ivermectin, 200 µg/kg/day until negative stool examination persists for 2 weeks is strongly suggested4. In patients where oral administration was not feasible veterinary preparation of ivermectin has been used subcutaneously or per rectum for the best interest of the patient in isolated cases as there is no parenteral ivermectin licensed for human use10. Discontinuation or reduction of immunosuppressive therapy, if possible is equally important in treatment of hyperinfection or disseminated disease. Both hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease are potential medical emergencies with mortality rate as high as 87% and 100% respectively in immunocompromised patients if remain untreated4. Therefore, distinguishing between the two is not essential as far as management is concerned.

In conclusion, patients with COPD may occasionally present with Strongyloides hyperinfection mimicking exacerbation. High index of suspicion should be maintained in patients receiving or received corticosteroid in the recent past, frequent exacerbations despite optimal medical management, or lack of expected response to the standard therapy for exacerbation. Multiple stool and sputum samples should be examined in such patients to exclude Strongyloides hyperinfection irrespective of peripheral eosinophilia. Oral ivermectin is the preferred anti-helminthic along with appropriate antibiotic in presence of bacteraemia.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:2355–2365.

2. Aaron SD. Management and prevention of exacerbations of COPD. BMJ. 2014; 349:g5237.

3. Kassalik M, Monkemuller K. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011; 7:766–768.

4. Mejia R, Nutman TB. Screening, prevention, and treatment for hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated infections caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012; 25:458–463.

5. Buonfrate D, Requena-Mendez A, Angheben A, Munoz J, Gobbi F, Van Den Ende J, et al. Severe strongyloidiasis: a systematic review of case reports. BMC Infect Dis. 2013; 13:78.

6. Ghoshal U, Khanduja S, Chaudhury N, Gangwar D, Ghoshal UC. A series on intestinal strongyloidiasis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Trop Gastroenterol. 2012; 33:135–139.

7. Ortiz Romero Mdel M, Leon Martinez MD, Munoz Perez MAz, Altuna Cuesta A, Cano Sanchez A, Hernandez Martinez J. Strongyloides stercoralys as an unusual cause of COPD exacerbation. Arch Bronconeumol. 2008; 44:451–453.

8. Liu HC, Hsu JY, Chang KM. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection presenting with symptoms mimicking acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Chin Med Assoc. 2009; 72:442–445.

9. Vigg A, Mantri S, Reddy VA, Biyani V. Acute respiratory distress syndrome due to Strongyloides stercoralis in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006; 48:67–69.

10. Feely NM, Waghorn DJ, Dexter T, Gallen I, Chiodini P. Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection: difficulties in diagnosis and treatment. Anaesthesia. 2010; 65:298–301.

11. Woodring JH, Halfhill H 2nd, Berger R, Reed JC, Moser N. Clinical and imaging features of pulmonary strongyloidiasis. South Med J. 1996; 89:10–19.

12. Choi KS, Whang YN, Kim YJ, Yang YM, Yoon K, Kim JK, et al. A case of hyperinfection syndrome with Strongyloides stercoralis. Korean J Parasitol. 1985; 23:236–240.

13. Lee SK, Shin BM, Khang SK, Chai JY, Kook J, Hong ST, et al. Nine cases of strongyloidiasis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1994; 32:49–52.

14. Hong SJ, Han JH. A case of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Korean J Parasitol. 1999; 37:117–120.

15. Kim YK, Kim H, Park YC, Lee MH, Chung ES, Lee SJ, et al. A case of hyperinfection with Strongyloides stercoralis in an immunosuppressed patient. Korean J Intern Med. 1989; 4:165–170.

16. Kim J, Joo HS, Ko HM, Na MS, Hwang SH, Im JC. A case of fatal hyperinfective strongyloidiasis with discovery of autoinfective filariform larvae in sputum. Korean J Parasitol. 2005; 43:51–55.

17. Kim YJ, Ahn MJ, Park KC, Lee HY, Kim KH, Byeon KM, et al. Pulmonary strongyloidiasis with alveolar hemorrhage in a patient receiving chemotherapy. Korean J Med. 2009; 76:502–505.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material can be found in the journal homepage (http://www.e-trd.org).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download