Abstract

Systemic vasculitis involving the lung is a rare manifestation of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and secondary vasculitis is considered to have poor prognosis. A 44-year-old man presented with fever and dyspnea of 1 month duration. A chest radiograph revealed bilateral multiple wedge shaped consolidations. In addition, the results of a percutaneous needle biopsy for non-resolving pneumonia were compatible with pulmonary vasculitis. Bone marrow biopsy was performed due to the persistence of unexplained anemia and the patient was diagnosed with MDS. We reported a case of secondary vasculitis presenting as non-resolving pneumonia, later diagnosed as paraneoplastic syndrome of undiagnosed MDS. The cytopenia and vasculitis improved after a short course of glucocorticoid treatment, and there was no recurrence despite the progression of underlying MDS.

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is a clonal stem cell disorder that is characterized by ineffective hematopoiesis, and which can progress to acute leukemia. After Dreyfus et al.1 described the six cases of MDS associated with cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis in 1981, there had been several reports of systemic autoimmune features associated with MDS23. Although the prognosis of other autoimmune manifestations presented conflicting results, the prognosis of MDS with vasculitis is appeared to be worse than MDS without vasculitis245. We report a case of pulmonary and cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis as an initial presentation of MDS, which was completely resolved after a short course of glucocorticoid treatment without recurrence.

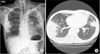

A 44-year-old man presented to our emergency department with a fever, and feeling of dyspnea that had persisted for one month. He was a chronic alcoholic, and diagnosed with megaloblastic anemia 5 years earlier, but he never visited a hospital since then. He was acutely ill, with blood pressure of 110/66 mm Hg, pulse rate of 126 beats per minute, body temperature of 38℃, respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 94% at room air. Crackles were present in both lungs, and pitting edema was observed in both legs. Chest radiography and chest computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral multiple wedge shaped consolidations in a subpleural area, with a small amount of pleural effusion (Figure 1).

Laboratory tests revealed a white cell count of 7,600/µL (neutrophil, 74%; eosinophil, 0.7%), hemoglobin concentration of 5.6 g/dL (reticulocyte, 1.2%; mean corpuscular volume, 114 µm2), platelet count of 182,000/µL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 46 mm/hr, and C-reactive protein level of 13.6 g/dL. Analysis of the patient's arterial blood gases indicated a PaO2 of 58 mm Hg, PaCO2 of 33 mm Hg, HCO3 of 31 mm Hg, and SaO2 of 94%. Results of liver and renal function tests, except aspartate aminotransferase (91 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (64 U/L), and bilirubin (0.6 mg/dL) were within normal range. Owing to the possibility of community-acquired pneumonia, a course of empirical antibiotics was initiated, and the patient received a transfusion of packed red blood cells to relieve symptomatic anemia. However, cultures for common bacteria, acid-fast bacilli, and fungi were all negative; a simple chest radiography became worsened; fever up to 40℃ persisted despite antibiotic therapy; and he developed multiple painful, erythematous, palpable rashes on both lower legs (Figure 2). We performed a skin biopsy to differentiate such as a drug rash or a transfusion reaction, but microscopic examination revealed the presence of neutrophilic infiltration in perivascular and interstitial area, which was compatible with cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 3). Percutaneous needle biopsy was followed to rule out organizing pneumonia or consolidative lung cancer including lymphoma. However, the results of the needle biopsy indicated necrotizing vasculitis with perivascular infiltration of neutrophils and lymphocytes, granuloma formation, and intraluminal fibrosis, which were compatible with a diagnosis of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure 4). Serologic tests were all negative for venereal disease, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B and C, human immunodeficiency virus antibodies, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), rheumatoid factor (RF), and cryoglobulin. There was no specific finding in abdominal CT scan. Since anemia persisted even after transfusion, we performed bone marrow aspiration with biopsy to identify the cause of unexplained macrocytic anemia. Evaluation of the bone marrow revealed hypercellularity (80%) that was abnormal for the his age, blast count of 2.6%, decreased erythropoiesis, and dysmegakaryopoiesis with karyotype of 46 XY,+1,der(1;7)(q10;q10). Finally, he was diagnosed as MDS, especially type of refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia.

Treatment of intravenous methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg) was started for immunologic manifestations, and fever subsided immediately. After 3 days, the patient's skin and lung lesions began to improve (Figure 5A), and his anemia improved. Since the identified karyotype was associated with poor prognostic outcome which has potential of progress to acute leukemia, we recommended him to undergo allohematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) as treatment for MDS. He refused our suggestion; however, and insisted on being discharged from our hospital, so we prescribed him an oral corticosteroid for 1 month, serially tapering the dosage every week.

After 1 year, he returned to our emergency department complaining of left flank pain. CT scans of the patient's abdomen revealed splenomegaly, and leukemic transformation was suspected on peripheral blood smear. His chest radiograph, however, showed improvement of pulmonary vasculitis compared to 1 year before, despite no further therapeutic intervention (Figure 5B). We then transferred him to another facility to undergo bone marrow transplantation.

In MDS patients, systemic autoimmune diseases could be associated as paraneoplastic syndrome, such as vasculitis, arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, pulmonary infiltrates, and peripheral neuropathy2345. The prevalence of autoimmune disease in MDS is generally known to be between 10% and 20%67. Median survival of MDS patients is reported as 25 months; however, median survival of MDS patient with autoimmune disease is only 9 months2. Even though there were some disagreements about the prognosis of MDS accompanying other autoimmune manifestations, MDS with vasculitis consistently reported poor prognosis with high mortality rates489. Death from vasculitis-related disease were described in previous reports, which includes hemorrhage, embolism, and infection associated with immunosuppressive therapy, or unknown cause210. Laboratory abnormalities such as hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and presence of ANA, ANCA, RF, and cryoglubulin could occur28.

Median age of MDS is older than 70 years and incidence of MDS increases with age11. However, our patient was 45 years old that is lower than median age of de novo MDS. Furthermore, karyotype was 46 XY,+1,der(1;7)(q10;q10) that can be seen in treatment related MDS/acute myeloid leukemia. We investigated his socio-occupational history and medical history, but he had no exposure of chemicals such as benzene or pesticide. He was severe alcoholic for more than 20 years and he was smoker as well. There are a few studies of association between alcohol consumption and the risk of MDS, but results are inconclusive1213. Considering the age and clinical manifestations, our patient is somewhat different from general case of de novo MDS, however, there is no evidence of therapy related or secondary MDS.

The mechanism of this immunologic phenomenon in MDS is not clear, but autoimmunity is believed to be triggered by increased apoptosis in the dysplastic bone marrow. Kiladjian et al.14 discovered that patients of MDS with autoimmune disease had significantly fewer gamma-delta T-cells than those of MDS without autoimmune disease. Gamma-delta T-cells play an important role in the immune reaction against tumor cells, by producing tumor necrosis factor α and interferon γ14. Several studies have reported that T regulatory cells (Tregs), which have a role in the maintenance of immune tolerance, are involved in the etiology of MDS, and their expansion results in suppression of host anti-tumor responses in malignant disease. Kordasti et al.15 reported that MDS patients who scored highly on the International Prognostic Scoring System had higher Treg percentages.

In this report, we have described a case of concurrently diagnosed MDS and leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving the lung and skin, which improved after high dose corticosteroid therapy. The patient's anemia also resolved, which may be explained by improving anemia of chronic disease rather than bone marrow response of MDS to steroid therapy. Since we predicted that immunologic manifestations would be aggravated without MDS treatment, we recommend early allo-HSCT. However, his vasculitis did not recur after short course of steroid therapy, despite progression of MDS.

In conclusion, nonresolving pneumonia can be initial manifestation of MDS, and treatment of vasculitis prior to MDS may be better approach to avoid fatal complications of this paraneoplastic syndrome.

Figures and Tables

Figure 2

Cutaneous lesions of bilateral lower legs were later revealed as cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Figure 3

(A) Heavy, perivascular and interstitial neutrophilic infiltration (arrowhead) are present (H&E stain, ×40). (B) Fibrinoid necrosis of the small blood vessels with fibrin extravasation and leukocytosis forming nuclear dust (arrowhead) are visible on skin biopsy (H&E stain, ×200).

References

1. Dreyfus B, Vernant JP, Wechsler J, Imbert M, De Prost Y, Reyes F, et al. Refractory anaemia with an excess of myeloblasts and cutaneous vasculitis (author's transl). Nouv Rev Fr Hematol. 1981; 23:115–121.

2. Enright H, Jacob HS, Vercellotti G, Howe R, Belzer M, Miller W. Paraneoplastic autoimmune phenomena in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: response to immunosuppressive therapy. Br J Haematol. 1995; 91:403–408.

3. Giannouli S, Voulgarelis M, Zintzaras E, Tzioufas AG, Moutsopoulos HM. Autoimmune phenomena in myelodysplastic syndromes: a 4-yr prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004; 43:626–632.

4. Belizna C, Subra JF, Henrion D, Ghali A, Renier G, Royer M, et al. Prognosis of vasculitis associated myelodysplasia. Autoimmun Rev. 2013; 12:943–946.

5. de Hollanda A, Beucher A, Henrion D, Ghali A, Lavigne C, Levesque H, et al. Systemic and immune manifestations in myelodysplasia: a multicenter retrospective study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011; 63:1188–1194.

6. Enright H, Miller W. Autoimmune phenomena in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997; 24:483–489.

7. van Rijn RS, Wittebol S, Graafland AD, Kramer MH. Immunologic phenomena as the first sign of myelodysplastic syndrome. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2001; 145:1529–1533.

8. Al Ustwani O, Ford LA, Sait SJ, Block AM, Barcos M, Vigil CE, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes and autoimmune diseases: case series and review of literature. Leuk Res. 2013; 37:894–899.

9. Saif MW, Hopkins JL, Gore SD. Autoimmune phenomena in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002; 43:2083–2092.

10. Braun T, Fenaux P. Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and autoimmune disorders (AD): cause or consequence? Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2013; 26:327–336.

11. Ma X, Does M, Raza A, Mayne ST. Myelodysplastic syndromes: incidence and survival in the United States. Cancer. 2007; 109:1536–1542.

12. Jin J, Yu M, Hu C, Ye L, Xie L, Chen F, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of myelodysplastic syndromes: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014; 2:1115–1120.

13. Du Y, Fryzek J, Sekeres MA, Taioli E. Smoking and alcohol intake as risk factors for myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Leuk Res. 2010; 34:1–5.

14. Kiladjian JJ, Visentin G, Viey E, Chevret S, Eclache V, Stirnemann J, et al. Activation of cytotoxic T-cell receptor gammadelta T lymphocytes in response to specific stimulation in myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica. 2008; 93:381–389.

15. Kordasti SY, Ingram W, Hayden J, Darling D, Barber L, Afzali B, et al. CD4+CD25high Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Blood. 2007; 110:847–850.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download