Abstract

This is a report of the first South Korean case of a lung disease caused by Mycobacterium simiae. The patient was a previously healthy 52-year-old female. All serial isolates were identified as M. simiae by multi-locus sequencing analysis, based on hsp65, rpoB, 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacer, and 16S rRNA fragments. A chest radiography revealed deterioration, and the follow-up sputum cultures were persistently positive, despite combination antibiotic treatment, including azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first confirmed case of a lung disease caused by M. simiae in South Korea.

Mycobacterium simiae, a slow-growing, photochromogenic nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM) pathogen, was first isolated from monkeys in 19651. M. simiae is a rare cause of NTM lung disease. Most cases of M. simiae infection have been reported from the southwestern United States and Middle Eastern countries including Israel and Iran23. Recently, its isolation has been reported from other regions, including Netherlands4.

Although M. simiae is often isolated from clinical specimens, M. simiae is considered to be not an obligate pathogen1. Previous studies have suggested that about 20% of M. simiae isolates are clinically relevant4. M. simiae is usually isolated from respiratory specimens, and most case reports are immunocompromised hosts such as patients with acquired immune-deficiency syndrome, cancer, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

We hereby describe a case of NTM lung disease caused by M. simiae that was identified using 16S rRNA, 16S-23S rRNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS), rpoB and hsp65 gene sequencing. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first confirmed case of lung disease caused by M. simiae in a Korean patient.

A 52-year-old Korean woman was referred to our hospital with mild, productive cough and blood-tinged sputum. The patient was an otherwise healthy, non-smoker and did not have a history of pulmonary tuberculosis. She had lived in Hanoi, Vietnam for the past 7 years after her family moved from Korea.

Physical examination showed that the patient was 160.7 cm tall and weighed 49.8 kg. Laboratory tests results were unremarkable, including normal levels of white blood cell count (4,690/mm3), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (14 mm/hr), and C-reactive protein (0.03 mg/dL). Human immunodeficiency virus antibody test was negative. Chest radiograph and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan revealed multifocal bronchiectasis and bronchiolitis in the right middle lobe and lingular division of the left upper lobe that suggested the nodular bronchiectatic form of NTM lung disease (Figure 1).

Her sputum showed trace (1-3/300 high-power field) acid-fast bacilli staining, and NTM were isolated three times in both liquid and solid culture media. Initial species identification using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-reverse blot hybridization assay method based on rpoB gene (REBA Myco-ID; M&D Inc., Wonju, Korea) was Mycobacterium genavense/M. simiae in all three NTM isolates5. For exact species identification of the isolates, sequencing analysis of the nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequence and partial ITS, rpoB, and hsp65 sequences was performed6789. The 16S rRNA and ITS sequences were 100% identical to those of the M. simiae type strain ATCC 25275T (GenBank accession Nos. NR117227 and AB026694, respectively), and the rpoB sequence showed 99.9% similarity (only 1-bp mismatch) to that of the M. simiae type strain ATCC 25275T (GenBank accession No. GQ153313). The hsp65 sequence showed 99.3% similarity to that of the M. simiae strain IEC4 (GenBank accession No. HM056116). Phylogenetic analysis based on rpoB sequence of the SMC-sim-001 isolated from the patient in this report and of those of closely related species within the slow growing mycobacteria allocated this strain to M. simiae (Figure 2). The GenBank accession numbers and corresponding sequences of 17 species compared with SMC-sim-001 were obtained from the GenBank sequence database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Drug susceptibility testing was performed using a broth microdilution method according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute10, revealing that the isolate was resistant to clarithromycin (minimal inhibitory concentration [MIC], 32 µg/mL), ethambutol (MIC, >32 µg/mL), rifampin (MIC, >16 µg/mL), moxifloxacin (MIC, 16 µg/mL), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (MIC, 16/304 µg/mL), and linezolid (MIC, >64 µg/mL). Sequence analysis of the rrl gene revealed no mutation at positions 2058 and 2059, which is the mechanism of macrolide resistance11.

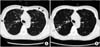

The patient was finally diagnosed with M. simiae lung disease. She received combination antibiotic treatment including azithromycin (250 mg daily), ethambutol (800 mg daily), and rifampin (450 mg daily). Moxifloxacin (400 mg daily) was added to the treatment regimen because sputum cultures were persistently positive 6 months after antibiotic treatment. Despite a total of 12-months of combination antibiotic treatment including azithromycin, ethambutol, rifampin, and moxifloxacin, the patient's symptoms including productive cough and hemoptysis worsened, follow-up sputum cultures were persistently positive, and HRCT revealed radiological deterioration (Figure 3).

We report the first confirmed case of M. simiae lung disease in Korea. In this case, it was difficult to make an accurate species identification due to genetic similarities between M. genavense and M. simiae. When applying PCR-REBA on the rpoB gene to the species identification, there was cross-reactivity in terms of hybridization between two species. Thus, in these instances, further molecular techniques might be needed to differentially diagnose between the genetically close subspecies. We eventually identified M. simiae using 16S rRNA, ITS, rpoB, and hsp65 gene sequencing.

Like other NTM species, M. simiae lung disease in our patient could also be acquired from environmental exposures, as M. simiae isolates were found from soil and water resources312. Because our patient had lived in Vietnam during the past 7 years, it might be possible that M. simiae infection occurred in Korea or Vietnam. Interestingly, there has been no report of M. simiae isolation from clinical specimens in Korea or Vietnam.

Patients with M. simiae lung disease are old with a female predominace2. Underlying diseases such as diabetes mellitus, solid and hematologic malignancies, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are associated with M. simiae infection2. The most commonly reported symptoms were productive cough and chest radiography mainly showed nodular lesion, bronchiectasis, and cavitation413.

The optimal antibiotic regimen and treatment duration for M. simiae lung disease have yet to be established. In the 2007 American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines, clarithromycin-based regimens, which are similar to those of M. avium complex, are recommended for M. simiae lung disease1. In vitro, most M. simiae isolates are resistant to first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs14, and high rates of resistance to clarithromycin (75%), ethambutol (97%), and rifampin (97%) among M. simiae isolates have been reported15. Although some isolates of M. simiae are susceptibile in vitro to sufamethoxazole and linezolid, in vivo response has not been established1. Therefore, treatment outcomes in M. simiae lung disease are typically poor4.

Our patient initially received combination antibiotic treatment including azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin. Although moxifloxacin was added based on the suggestion of the 2007 ATS/IDSA guidelines1, sputum negative conversion could not be achieved. Further studies are required in order to improve treatment outcomes of M. simiae lung disease.

In summary, we report the first case of M. simiae lung disease identified by multi-locus sequence analysis in Korea. M. simiae should be considered as a possible etiologic pathogen of NTM lung disease. However, the optimal regimen and duration of treatment further to be investigated.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

A 52-year-old female with Mycobacterium simiae lung disease. (A) A plain chest radiograph shows nodular and micronodular opacities distributed in bilateral middle lung zones. (B) An axial high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) image shows multiple nodules or nodular consolidation in the lingular division of the left upper lobe and the superior segment of left lower lobe (arrowheads). (C) An axial HRCT image shows tubular bronchiectasis (arrows) in the right middle lobe and the lingular division of left upper lobe. Thus, the radiologic finding of this patient was the typical nodular bronchiectatic pattern of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease.

Figure 2

The phylogenetic position of SMC-sim-001 isolated from the patient in this report and other species belonging to the slow growing mycobacteria, based on the rpoB sequence. This tree was constructed using a neighbor-joining method. The percentages indicated at nodes represent bootstrap levels supported by 1,000 re-sampled datasets. Scale bars indicate evolutionary distance in base substitutions per site. M., Mycobacterium.

Figure 3

Radiologic comparison between before and after the treatment. (A) Initial high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the carinal level shows multiple micronodules and tree in bud lesions in the subpleural areas of both lungs (arrowheads). (B) Follow-up HRCT of same level at one year after the treatment reveals new nodule in the posterior segment of right upper lobe (arrow). Note: previously seen multiple micronodules were no longer there.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A120647) and by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2013R1A1A2060552).

References

1. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 175:367–416.

2. Maoz C, Shitrit D, Samra Z, Peled N, Kaufman L, Kramer MR, et al. Pulmonary Mycobacterium simiae infection: comparison with pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008; 27:945–950.

3. Velayati AA, Farnia P, Mozafari M, Malekshahian D, Seif S, Rahideh S, et al. Molecular epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolates from clinical and environmental sources of a metropolitan city. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e114428.

4. van Ingen J, Boeree MJ, Dekhuijzen PN, van Soolingen D. Clinical relevance of Mycobacterium simiae in pulmonary samples. Eur Respir J. 2008; 31:106–109.

5. Wang HY, Bang H, Kim S, Koh WJ, Lee H. Identification of Mycobacterium species in direct respiratory specimens using reverse blot hybridisation assay. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014; 18:1114–1120.

6. Ben Salah I, Adekambi T, Raoult D, Drancourt M. rpoB sequence-based identification of Mycobacterium avium complex species. Microbiology. 2008; 154:3715–3723.

7. Frothingham R, Wilson KH. Sequence-based differentiation of strains in the Mycobacterium avium complex. J Bacteriol. 1993; 175:2818–2825.

8. Turenne CY, Tschetter L, Wolfe J, Kabani A. Necessity of quality-controlled 16S rRNA gene sequence databases: identifying nontuberculous Mycobacterium species. J Clin Microbiol. 2001; 39:3637–3648.

9. Adekambi T, Colson P, Drancourt M. rpoB-based identification of nonpigmented and late-pigmenting rapidly growing mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2003; 41:5699–5708.

10. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI document No. M24-A2. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes; approved standard. 2nd ed. Wayne: Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute;2011.

11. Meier A, Heifets L, Wallace RJ Jr, Zhang Y, Brown BA, Sander P, et al. Molecular mechanisms of clarithromycin resistance in Mycobacterium avium: observation of multiple 23S rDNA mutations in a clonal population. J Infect Dis. 1996; 174:354–360.

12. El Sahly HM, Septimus E, Soini H, Septimus J, Wallace RJ, Pan X, et al. Mycobacterium simiae pseudo-outbreak resulting from a contaminated hospital water supply in Houston, Texas. Clin Infect Dis. 2002; 35:802–807.

13. Baghaei P, Tabarsi P, Farnia P, Marjani M, Sheikholeslami FM, Chitsaz M, et al. Pulmonary disease caused by Mycobacterium simiae in Iran's national referral center for tuberculosis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012; 6:23–28.

14. van Ingen J, Totten SE, Heifets LB, Boeree MJ, Daley CL. Drug susceptibility testing and pharmacokinetics question current treatment regimens in Mycobacterium simiae complex disease. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012; 39:173–176.

15. van Ingen J, van der Laan T, Dekhuijzen R, Boeree M, van Soolingen D. In vitro drug susceptibility of 2275 clinical nontuberculous Mycobacterium isolates of 49 species in The Netherlands. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010; 35:169–173.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download