Abstract

Statins lower the hyperlipidemia and reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events and related mortality. A 60-year-old man who was diagnosed with a transient ischemic attack was started on acetyl-L-carnitine, cilostazol, and rosuvastatin. After rosuvastatin treatment for 4 weeks, the patient presented with sudden onset fever, cough, and dyspnea. His symptoms were aggravated despite empirical antibiotic treatment. All infectious pathogens were excluded based on results of culture and polymerase chain reaction of the bronchoscopic wash specimens. Chest radiography showed diffuse ground-glass opacities in both lungs, along with several subpleural ground-glass opacity nodules; and a foamy alveolar macrophage appearance was confirmed on bronchoalveolar lavage. We suspected rosuvastatin-induced lung injury, discontinued rosuvastatin and initiated prednisolone 1 mg/kg tapered over 2weeks. After initiating steroid therapy, his symptoms and radiologic findings significantly improved. We suggest that clinicians should be aware of the potential for rosuvastatin-induced lung injury.

Statins, hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA reductase inhibitors, are known to lower the plasma low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level and reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events and mortality12. Currently available statins include lovastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin, fluvastatin, atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and pitavastatin. Statins have a low frequency of side effects including hepatotoxicity, myotoxicity, and proteinuria23. However, adverse reactions involving the respiratory system are uncommon. Several cases of statin-induced pulmonary toxicity have been reported456. Regarding statins, most cases were associated with simvastatin, fluvastatin, and atorvastatin. Interstitial lung disease secondary to rosuvastatin is rare78. In addition, rosuvastatin-induced interstitial lung disease has not been reported in Korea. Herein, we will present a patient who was diagnosed with drug-induced interstitial lung disease (DILD) secondary to rosuvastatin.

A 60-year-old man who never smoker was a professor of humanities and had no experiences of exposure to noxious materials. He has not traveled or moved anywhere in recent years. He had been diagnosed with acute hypersensitivity pneumonitis 18 months previously and was treated with a steroid therapy for 6 weeks. Cause of hypersensitivity pneumonitis had been confirmed as being fungus derived from old wallpapers at the time. After the cause removed, it had not recurred over 2 years. He had also been administered metformin 500 mg daily for 16 months for diabetes mellitus. For a transient ischemic attack secondary to vertebral artery stenosis, he was hospitalized and started on acetyl-L-carnitine, cilostazol, and rosuvastatin according to the following schedule: acetyl-L-carnitine, 500 mg, once daily for 48 days prior to this hospitalization; cilostazol, 100 mg, twice daily; and rosuvastatin, 5 mg, once daily for 27 days prior to this hospitalization. While continuing those medications, he developed a fever and cough 3 days prior to this hospital visit. Although he was prescribed an antibiotic (Augmentin) for 3 days at a local clinic, his dyspnea, cough, and fever gradually increased. He was referred to our hospital for proper evaluation and management. He had no known drug allergies.

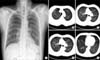

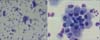

Upon admission, the patient's vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 116/77 mm Hg; pulse, 114 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 26 breaths per minute; and body temperature, 36.9℃. On physical examination, a coarse breath sound with fine crackles but without wheezing was heard upon auscultation of both lungs. The patient's laboratory test results were as follows: hemoglobin, 14.1 g/dL; white blood cell count, 8,770 cells/µL (neutrophils, 62.6%; lymphocytes, 26.0%; monocytes, 7.2%; eosinophils, 3.9%; and basophils, 0.3%); and platelet count, 391,000 cells/µL. The patient's serum biochemistry test results revealed the following: aspartate aminotransferase, 35 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 35 IU/L; total bilirubin, 0.4 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 311 IU/L; total protein, 7.6 g/dL; albumin, 4.0 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 26.0 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.84 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 106 mg/dL; C-reactive protein, 1.06 mg/dL; and LDL cholesterol, 56 mg/dL. His coagulation profile was within normal limits. A urinalysis with microscopy was clear. An arterial blood gas analysis of the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) was conducted with the patient breathing room air and revealed the following: pH, 7.46; partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), 54.6 mm Hg; partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2), 37.4 mm Hg; bicarbonate (HCO3-), 26.0 mEq/L; and saturation level of oxygen (SaO2), 85.9%. A chest radiograph showed a subtle, diffuse ground-glass opacity in both lower lung fields and subsegmental atelectasis in the left lower lobe. A chest computed tomography scan revealed diffuse ill-defined ground-glass opacities with septal line thickening bilaterally, combined with several subpleural ground-glass opacity nodules (Figure 1). A pulmonary function test revealed the following: forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio, 102; FEV1, 2.8 L (94%); FVC, 3.47 L (92%); and diffuse capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), 57%. Based on his past medical history, clinical symptoms, and laboratory findings, a diagnosis of DILD was suspected. Consequently, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. There were no endobronchial lesions revealed with bronchoscopy. The BAL fluid results were as follows: white blood cell count, 480 cells/µL (neutrophils, 9%; lymphocytes, 30%; macrophages, 57%; eosinophils, 4%; and basophils, 0%); and red blood cell count, 30 cells/µL. Microbiological culture and polymerase chain reaction of the bronchoscopic wash specimens were negative for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, pneumococcus and respiratory virus. The real-time polymerase chain reaction of bronchial washing specimens was performed as following: Mycoplasma, Chlamydia, Legionella, Bordetella, Haemophilus pneumonia, adenovirus, rhinovirus, coronavirus, influenza virus A and B, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus A and B, bocavirus, metapneumovirus. The results were all negative. Additionally, the urine antigen and immunologic study were performed to exclude others pathogen. The results revealed the following: streptococcal pneumonia and Legionella urinary antigen, negative; Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgG/IgM, negative; and Chlamydia pneumoniae IgG (17.65, positive; normal range, <9 index), IgM (4.62, negative; normal range, <9 index). According to the cytology, the majority of the alveolar macrophages had a foamy appearance (Figure 2). To make a differential diagnosis of connective disease or allergic disease, immunologic studies and multiple allergosorbent test system (MAST) were performed as follow: all allergens of MAST, class 0 (0.00-0.34 IU/mL); rheumatoid factor, negative; C3 complement, 135.00 mg/dL (normal range, 90-180 mg/dL); C4 complement, 42.20 mg/dL (normal range, 10-40 mg/dL); anti-nuclear antibodies and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, negative.

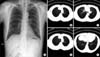

Considering the previous reports and past drug history, rosuvastatin was strongly suspected as the cause of the patient's DILD. Thus, rosuvastatin was discontinued, and steroid therapy (prednisolone, 1 mg/kg of body weight) was initiated. After the steroid therapy, the patient's symptoms improved. The prednisolone dose was gradually tapered over 2 weeks. Two weeks later, the patient was in complete remission according to a chest radiograph, and the previously noted diffuse ground-glass opacities in both lung fields had disappeared (Figure 3).

Statins are indicated for the treatment of hyperlipidemia and the prevention of cardiovascular events for patients with multiple risk factors. Although statins appear to be safe and well tolerated clinically, statins have a low frequency of side effects including hepatotoxicity, myotoxicity, and proteinuria23. However, adverse reactions involving the respiratory system are uncommon. Several pulmonary toxicity cases secondary to statins have been reported456. The prevalence of statininduced interstitial pneumonitis (SILI) that has been mainly associated with simvastatin, fluvastatin, and atorvastatin was high7. Rosuvastatin-induced interstitial pneumonitis has been rarely reported. To our knowledge, just 3 cases in Taiwan and 1 case in the United States have been reported78. In addition, rosuvastatin-induced interstitial lung disease has not been reported in Korea, to our knowledge.

A definite mechanism for SILI is not yet known. However, some authors proposed that the potential toxicity mechanism might be mediated by intracellular lipid metabolism, mitochondrial metabolism, and immunologic response, as well as some genetic or other predisposing factors7. Diagnosis of SILI generally depends on the relationship between causative agents and clinical symptoms, as well as radiologic findings and the exclusion of infectious diseases, because of its unclear mechanism.

Although the histopathological findings are also non-diagnostic, based on prior reports and studies, the possibility of diagnosis is significantly increased if the alveolar macrophages have a foamy appearance, as confirmed by cytology, along with the patient's clinical history8. Furthermore, some reports suggested that the most prominent feature of DILD on BAL fluid was a lymphocytic alveolitis either pure or associated with neutrophil and/or eosinophilic alveolitis along with an imbalance in T lymphocyte phenotype9.

In our case, infectious diseases were excluded based on the negative microbial culture results. In addition, the patient's symptoms and bilateral infiltration began after starting rosuvastatin that was revealed by chest radiology. The alveolar macrophages finally had a foamy appearance that was revealed by cytology. The alveolar macrophages finally had a foamy appearance that was revealed by cytology with increased lymphocytes and eosinophils on cellular profile of BAL fluid. Thereafter, after discontinuing rosuvastatin and initiating steroid therapy, the patient's symptoms and radiologic findings had improved. Therefore, to our knowledge, our patient was the first diagnosed with rosuvastatin-induced interstitial lung disease in Korea. In comparing with the previous cases in Taiwan and the United States, clinical course, radiologic findings and cytology were similar to our case. And they also did not perform a lung biopsy. However, increasing lymphocytes and eosinophils along with the predominance of macrophage on cellular profile of BAL fluid was revealed only in our patient.

We believe a foamy macrophage appearance could help in the diagnosis of SILI, coupled with the clinical symptoms and radiologic findings, and clinicians should consider the potential for rosuvastatin-induced lung injury.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

(A-E) Chest radiography showed subtle diffuse ground glass opacity in both lower lobe field and subsegmental atelectasis in left lower lobe field on admission. A computed tomography scan of the chest showed diffuse ill-defined ground glass opacity with septal line thickening in bilateral lung fields combined with several subpleural ground glass opacity nodules on admission.

References

1. Rosenson RS, Tangney CC. Antiatherothrombotic properties of statins: implications for cardiovascular event reduction. JAMA. 1998; 279:1643–1650.

2. Bellosta S, Paoletti R, Corsini A. Safety of statins: focus on clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Circulation. 2004; 109:23 Suppl 1. III50–III57.

3. Alsheikh-Ali AA, Ambrose MS, Kuvin JT, Karas RH. The safety of rosuvastatin as used in common clinical practice: a postmarketing analysis. Circulation. 2005; 111:3051–3057.

4. Hill C, Zeitz C, Kirkham B. Dermatomyositis with lung involvement in a patient treated with simvastatin. Aust N Z J Med. 1995; 25:745–746.

5. Liebhaber MI, Wright RS, Gelberg HJ, Dyer Z, Kupperman JL. Polymyalgia, hypersensitivity pneumonitis and other reactions in patients receiving HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors: a report of ten cases. Chest. 1999; 115:886–889.

6. Veyrac G, Cellerin L, Jolliet P. A case of interstitial lung disease with atorvastatin (Tahor) and a review of the literature about these effects observed under statins. Therapie. 2006; 61:57–67.

7. Fernandez AB, Karas RH, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Thompson PD. Statins and interstitial lung disease: a systematic review of the literature and of food and drug administration adverse event reports. Chest. 2008; 134:824–830.

8. Huang LK, Tsai MJ, Tsai HC, Chao HS, Lin FC, Chang SC. Statin-induced lung injury: diagnostic clue and outcome. Postgrad Med J. 2013; 89:14–19.

9. Matsuno O. Drug-induced interstitial lung disease: mechanisms and best diagnostic approaches. Respir Res. 2012; 13:39.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download