Abstract

Plasmacytomas are extramedullary accumulations of plasma cells originating from soft tissue. Mediastinal plasmacytoma is a rare presentation. A 67-year-old man recovered after antibiotic treatment for community-acquired pneumonia. However, on convalescent chest radiography after 3 months, mass like lesion at the right lower lung field was newly detected. Follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) revealed an increase in the extent of the right posterior mediastinal mass that we had considered to be pneumonic consolidations on previous CT scans. Through percutaneous needle biopsy, we diagnosed IgG kappa type extramedullary plasmacytoma of the posterior mediastinum.

Extramedullary plasmacytomas (EMPs), a category of plasma cell malignancies, are characterized by localized monoclonal plasma cell proliferation forming a solitary lesion outside the bone marrow1. These are associated with the upper aerodigestive tract in about 80% of cases, and manifest as multiple myeloma, primary amyloidosis, or monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance1. Plasmacytomas may be primary or secondary to disseminated multiple myeloma and may arise from medullary or extramedullary sites1.

The mediastinal involvement of EMP is rare, and diagnosis of plasmacytoma could be often delayed2. However, because EMP can be the sequence of proceeding for multiple myeloma, these tumors need to be diagnosed early and treated to prevent further morbidity. We describe a case of posterior mediastinal plasmacytoma with delayed diagnosis due to clinical improvement after antimicrobial therapy for community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) with a review of the literature.

A 67-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with febrile sensation and cough for 3 days. He had no other underlying chronic disease. He was an ex-smoker (20 pack-years) and did not have a history of alcohol abuse. His vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 140/82 mm Hg; heart rate, 68 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 20 per minute; and body temperature, 38.5℃. Auscultation revealed coarse crackles in both lower lung fields.

Chest radiography showed multiple pulmonary infiltrations in the right lung fields (Figure 1A). White blood cell count was 8,000/mm3 with 76.0% segmented neutrophils, 13.7% lymphocytes, and 1% eosinophils. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin were 23.34 mg/dL and 0.579 mg/dL, respectively. Other routine blood chemistry tests were all normal. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed pH 7.439, PCO2 36.3 mm Hg, PO2 52.4 mm Hg, and HCO3- 24.9 mmol/L.

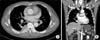

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was performed, and revealed multiple pulmonary consolidations, ground-glass opacities, and interstitial septal thickenings in both lower lung fields (Figure 2A, B). Based on these observations, we made a diagnosis of CAP and initiated antimicrobial therapy of intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g plus azithromycin 500 mg. After treatment of CAP, the clinical findings of the patient stabilized, and the patient was discharged on hospital day 4.

After three months, we performed a routine check-up of the patient. The patient had no definitive symptoms. Follow-up chest radiography showed resolution of multiple pulmonary consolidations throughout most of the lung fields, but a mass-like lesion without the loss of right cardiac borders at the right lower lobe field was observed (Figure 1B). Follow-up CT scans of the chest revealed interval improvements in pneumonic consolidations in both lower lung fields, but an increased mass in the right posterior mediastinum at T6-7 level that we had considered to be pneumonic consolidations on the previous CT scans was visible (Figure 2C, D). This oval and elongated mass with mild enhancement of soft tissue density without any bone destruction was observed (Figure 3A, B). Positron emission tomography using 2-[fluorine-18] fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) imaging and CT scans of the whole body except the brain revealed mild FDG uptake of maximum standardized uptake value 3.4 at the posterior mediastinal mass.

Percutaneous needle biopsy using ultrasound was performed. Lung ultrasound revealed an ill-defined, hypoechoic subpleural lesion measuring about 5.0 cm×2.7 cm at right paraspinal area of T6-7 level. And microscopic examination showed diffuse infiltrates of polymorphous and asynchronous plasma cells with large and eccentric nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant cytoplasm (Figure 4A). Immunohistochemistry revealed the biopsy was positive for CD138, the cytoplasm was diffusely reactive for monoclonal kappa-light chain (Figure 4B). Based on these findings, the posterior mediastinal mass was diagnosed as a IgG kappa type plasmacytoma.

We subsequently investigated the possibility of multiple myeloma. Laboratory tests showed an inverse albumin/globulin ratio (total protein, 10.7 g/dL; albumin, 3.0 g/dL; A/G ratio, 0.38). Serum hemoglobin, creatinine, and total calcium were 11.8 g/dL, 1.4 mg/dL, and 8.5 mg/dL, respectively. Immunofixation of serum showed monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-kappa type. In serum protein electrophoresis, the M spike level was 4.58 g/dL. Serum Ig determination revealed a markedly increased IgG level (6,993.1 mg/dL), and the level of β2-microglobulin was 3,674.2 ng/mL. On bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, plasma cells were increased up to 7.8% of all marrow nucleated cells. Those findings were consistent with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and insufficient for diagnostic criteria of symptomatic multiple myeloma. The patient was finally diagnosed as a posterior mediastinal plasmacytoma (IgG-kappa type). The patient was referred to the hematology department for proper treatment. This report was approved by the Ethical Review Committee.

EMPs result from monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells in soft tissues or organs outside the bone marrow, and constitute about 4% of plasma cell malignancies. Although most tumors (approximately 82%) occur in regions of the upper respiratory tract such as the oronasopharynx and paranasal sinuses, these tumors can also occur in the gastrointestinal tract, spleen, liver, lymph nodes, kidneys, thyroid gland, adrenal gland, ovary, testes, lung, pleura, pericardium, and skin1. The posterior mediastinal plasmacytoma as occurred in our case is rare, and most studies are case reports345.

While EMP of the upper respiratory tract develops frequently in men (male-to-female ratio ranges from 3:1 to 5:1), no predilection for thoracic involvement according to sex has been reported6. The most common age of onset is 50 to 60 years, and clinical signs depend on the location of the tumor6.

EMP can occur as a primary tumor without any bone marrow plasmacytosis, or as a manifestation of multiple myeloma with extramedullary involvement1. Before multiple myeloma enters into an aggressive phase, the disease is mostly contained within the bone marrow6. However, during the transformation phase, extramedullary manifestations can develop6. The incidence of EMP associated with multiple myeloma ranges from 7% to 17% in patients at the time of diagnosis, and 6% to 20% during the clinical course of the disease7.

Otherwise, EMP can be the sequences of proceedings for multiple myeloma. Moran et al.8 reported two cases of EMP presenting as a mediastinal mass, which preceded the onset of full-blown multiple myeloma. And the other report concerned that 10% to 30% of solitary EMP cases could be disseminated into multiple myeloma within the first 2 years9. Therefore, the presence of the EMP often provides a hint to the diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

In terms of posterior mediastinal manifestations of EMP, it should be differentiated from neurogenic tumor, lymphoma, and lymphangioma10. And EMP within thoracic cavity can present as lung nodule or mass, or as pulmonary consolidative patterns1112. In practice, EMP is highly indistinguishable from other thoracic disease and it is a great challenge to diagnose thoracic or mediastinal plasmacytoma.

In our case, we failed to detect underlying posterior mediastinal plasmacytoma at the time of initial admission because the patient had pneumonia that subsequently responded to antimicrobial therapy. Follow-up chest CT scans revealed an irregular enhancing mass at the right posterior mediastinum. Based on histology findings, we made a delayed diagnosis of posterior mediastinal plasmacytoma. In additioin, we suggested that EMP could be the sequences of proceedings for multiple myeloma. In our case, patient was diagnosed as a EMP coexisted with MGUS according to International myeloma working guidelines published in 200913. This case is rare because there are only three cases in PubMed which reported plasmacytoma of posterior mediastinum without multiple myeloma345. Furthermore, this is the second case report ever with rare IgG kappa type of plasmacytoma in posterior mediastinum3.

The management of plasmacytoma is entirely different for both types of plasma cell dyscrasias. Most cases of primary EMP without multiple myeloma are treated with surgery and/or radiation therapy, and clinical responses are generally good6. However, if the diagnosis of EMP is concurrent with multiple myeloma, the prognosis is very poor and treatment includes chemotherapy or autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation which is directed towards the underlying disease14.

In conclusion, this case suggests that plasmacytoma can manifest as a form of posterior mediastinal mass. And, because this disease cannot be often differentiated from pneumonic consolidations, careful monitoring may be required in some patients who recover after antimicrobial therapy of pneumonia.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Chest radiography images of the patient. (A) Initial chest radiography showing multiple pulmonary consolidations. (B) A mass-like lesion without the loss of right cardiac borders on a routine follow-up chest radiography after 3 months. |

| Figure 2Computed tomography (CT) scan images of the chest. (A, B) Initial chest CT scan showing multiple pulmonary consolidations at both lung fields. (C, D) Follow-up chest CT scan revealing an increased mass in the right posterior mediastinum with improvements in other pneumonic consolidations at other lung fields. |

| Figure 3(A, B) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan images of the chest after treatment of pneumonia. Chest CT scan revealing oval and elongated mass (arrow) with mild enhancement of soft tissue density without any bone destruction. |

| Figure 4(A) Microscopic examination showing diffuse infiltrates of plasma cells with large and eccentric nuclei with prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm (H&E stain, ×200). (B) Immunohistochemistry showing tumor cells with diffuse reactivity to cytoplasmic monoclonal kappa-light chain reactivity (×200). |

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the 2015 scientific promotion program funded by Jeju National University.

References

1. Alexiou C, Kau RJ, Dietzfelbinger H, Kremer M, Spiess JC, Schratzenstaller B, et al. Extramedullary plasmacytoma: tumor occurrence and therapeutic concepts. Cancer. 1999; 85:2305–2314.

2. Bataille R, Sany J. Solitary myeloma: clinical and prognostic features of a review of 114 cases. Cancer. 1981; 48:845–851.

3. Masood A, Hudhud KH, Hegazi A, Syed G. Mediastinal plasmacytoma with multiple myeloma presenting as a diagnostic dilemma. Cases J. 2008; 1:116.

4. Lee SY, Kim JH, Shin JS, Shin C, In KH, Kang KH, et al. A case of extramedullary plasmacytoma arising from the posterior mediastinum. Korean J Intern Med. 2005; 20:173–176.

5. Ganesh M, Sankar NS, Jagannathan R. Extramedullary plasmacytoma presenting as upper back pain. J R Soc Promot Health. 2000; 120:262–265.

6. Montero C, Souto A, Vidal I, Fernandez Mdel M, Blanco M, Verea H. Three cases of primary pulmonary plasmacytoma. Arch Bronconeumol. 2009; 45:564–566.

7. Oriol A. Multiple myeloma with extramedullary disease. Adv Ther. 2011; 28:Suppl 7. 1–6.

8. Moran CA, Suster S, Fishback NF, Koss MN. Extramedullary plasmacytomas presenting as mediastinal masses: clinicopathologic study of two cases preceding the onset of multiple myeloma. Mod Pathol. 1995; 8:257–259.

9. Husain M, Nguyen GK. Primary pulmonary plasmacytoma diagnosed by transthoracic needle aspiration cytology and immunocytochemistry. Acta Cytol. 1996; 40:622–624.

10. Agarwal PP, Seely JM, Matzinger FR. Case 130: mediastinal hemangioma. Radiology. 2008; 246:634–637.

11. Mohammad Taheri Z, Mohammadi F, Karbasi M, Seyfollahi L, Kahkoei S, Ghadiany M, et al. Primary pulmonary plasmacytoma with diffuse alveolar consolidation: a case report. Patholog Res Int. 2010; 2010:463465.

12. Horiuchi T, Hirokawa M, Oyama Y, Kitabayashi A, Satoh K, Shindoh T, et al. Diffuse pulmonary infiltrates as a roentgenographic manifestation of primary pulmonary plasmacytoma. Am J Med. 1998; 105:72–74.

13. Palumbo A, Sezer O, Kyle R, Miguel JS, Orlowski RZ, Moreau P, et al. International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for the management of multiple myeloma patients ineligible for standard high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2009; 23:1716–1730.

14. Chen HF, Wu TQ, Li ZY, Shen HS, Tang JQ, Fu WJ, et al. Extramedullary plasmacytoma in the presence of multiple myeloma: clinical correlates and prognostic relevance. Onco Targets Ther. 2012; 5:329–334.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download