Abstract

Interventional lung assist (iLA) effectively reduces CO2 retention and allows protective ventilation in cases of life-threatening hypercapnia. Despite the clinical efficacy of iLA, there are a few major limitations associated with the use of this approach, such as bleeding, thrombosis, and catheter-related limb ischemia. We presented two cases in which thrombotic complications developed during iLA. We demonstrated the two possible causes of thrombotic complications during iLA; stasis due to low blood flow and inadequate anticoagulation.

Interventional lung assist (iLA), which is performed using a device manufactured by Novalung (Talheim, Germany), has been used as rescue therapy in life-threatening forms of refractory hypercapnic respiratory failure1,2,3,4. The iLA system is characterized by a heparin-coated poly(4-methyl-2-pentyne) membrane with optimized blood flow, which is integrated into an arteriovenous bypass established by cannulation of the femoral artery and vein5. A blood flow setting of 1.0-1.5 L has been considered sufficient to reduce catheter-related distal limb ischemia and facilitate protective ventilation6. However, concerns regarding thrombotic complications exist at low blood flow settings with or without anticoagulation. These events can be fatal in critically ill patients. Here, we review two cases of thrombotic complications that developed during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support.

A 70-year-old man, who had undergone lung cancer resection 32 months ago, was admitted to the anesthesia department for stump (amputated finger) pain management. During hospitalization, the patient developed pneumonia, and the peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) decreased to 89% with mild dyspnea. On day 11 of hospitalization, SpO2 rapidly decreased to 68% while the patient was receiving 100% oxygen via a non-rebreather facemask, and conventional ventilation was initiated. Hypercapnia was intractable despite mechanical ventilation; therefore, he was placed on iLA (Table 1). On the second day of iLA, the iLA flow was zero due to clots in the circuit without anticoagulation (Figure 1); consequently, the iLA membrane was changed and heparin infusion was started. On the tenth day of iLA, clots formed again despite heparin infusion (Table 2). Ultimately, veno-venous ECMO was initiated for effective oxygenation. On the 11th day of ECMO, acute respiratory distress syndrome was not resolved, and the patient died of multi-organ failure.

A 61-year-old man was admitted to the emergency room because of a near-fatal asthma attack. The initial arterial blood gas analysis revealed the following findings: pH, 7.15; PaCO2, 66 mm Hg; PaO2, 66 mm Hg, and O2 saturation 86%. His mental functions gradually decreased despite conventional treatment for asthma. The patient's hypercapnia was intractable under conventional mechanical ventilation (Table 1). As such, iLA support was initiated within 2 hours after intubation with heparin infusion. After iLA insertion, hypercapnia resolved immediately. Extubation was done 32 hours after intubation, and iLA was removed 55 hours after insertion. After the removal of iLA, the patient complained about a new episode of dyspnea. Pulmonary embolism was diagnosed through a computed tomography scan (Figure 2) and anticoagulation treatment was initiated. On the ninth day, he was transferred to his hometown for follow-up treatment.

The iLA employs a low-gradient device designed to operate without a mechanical pump in an arteriovenous configuration7. The natural arteriovenous blood pressure gradient determines the flow through the oxygenator4. The patient's oxygenation predominantly depends on arteriovenous shunt volume, which is influenced by the cannula diameter and the patient's mean arterial blood pressure5. Jayroe et al.6 suggested that a blood flow of 1.0-1.5 L/min is sufficient to remove CO2 effectively, and a smaller cannula decreases the incidence of cannula-related limb ischemia. Further, other data showed that low blood flow settings decreased distal limb ischemia as well as effectively removed CO2 level in Asians with petite body figures7. However, stasis which originates from low flow may have an impact on venous thrombosis. Our cases suggest that this concern is not groundless.

Catheter thrombosis occurred 24 hours after iLA device insertion in case 1, and pulmonary thromboembolism was diagnosed 55 hours after iLA device insertion in case 2. From January 2012 to August 2013, we recorded two cases of thrombotic (28.5%) complications out of the seven cases in which iLA was employed. The incidence of thrombotic complications was exceptionally higher than that in previous studies, which showed cannula thrombosis rates of 1.9%5. In all seven cases, the diameter of the arterial cannula was 13 French (Fr), whereas the venous cannula was selected to be 2Fr larger so that flow resistance was not compromised. Our anticoagulation strategy used a similar protocol (activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT] level≥1.5 times the upper normal limit) to other studies1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. To achieve a prolongation of the aPTT time, heparin (Heparin-Natrium-25,000; 200-600 IU/hr) was continuously infused into the arterial cannula before the gas-exchange membrane. However, in case D and E in nonthrombotic group, anticoagulation was not initiated because of hemoperitoneum and hemoptysis (Table 3).

The first factor to be considered for the high incidence of thrombosis is the maintenance of low blood flow through iLA. Generally, the blood flow was maintained below 1 L/min in all cases of iLA in our hospital. Jayroe et al.6 suggested that a low blood flow of 1.0-1.5 L/min was sufficient to remove CO2 effectively; however, it possibly caused the stasis and formation of thrombosis. Furthermore, the biggest difference between our study and previous studies is the mean blood flow. In a previous prospective pilot study5, the thrombosis incidence was 1.9% when the mean blood flow was above 1.5 min/L. As we mentioned before, the blood flow depends on arteriovenous shunt volume, which is influenced by the diameter of the cannula and the patient's mean arterial blood pressure5. Even though the mean arterial pressure in these cases was maintained above 70 mm Hg, which is enough to produce adequate iLA flow, the blood flow was below 1.0 L/min. In previous studies from European countries and the United States, cannula sizes of 17Fr for veins and 15Fr for arteries had been used1,2,3,4,5,6; however, we used 15Fr for veins and 13Fr for arteries in proportion to the petite Asian body size to reduce catheter-related limb ischemia7. We assumed that the small size of the cannula caused low blood flow and stasis. Therefore, we suggest that an optimal cannula size be chosen to maintain a balance between prevention of thrombosis and distal limb ischemia. We recommend checking the femoral arterial diameter using Doppler ultrasound to determine an optimal cannula size that can maintain sufficient blood flow with adequate anticoagulation to reduce thrombosis. Unless a small cannula can sufficiently maintain flow rate, the transition to pumpdriven ECMO should be considered for maintenance of blood flow and gas exchange.

The second factor to be considered for the high incidence of thrombosis is inadequate anticoagulation. Although our anticoagulation strategy used a similar protocol (aPTT level≥1.5 times the upper normal limit) to other studies1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, aPTT level was not reaches to >1.5 times the upper normal limit. Even though the target aPTT level is between 55-70 seconds in iLA protocol of our hospital, aPTT level was ranged to 36.6-70.2 seconds between the first and the second catheter thrombosis in case 1 with heparinization. And the level was ranged to 27.1-81.1 seconds with heparinization in case 2. Therefore, strict target-achieved anticoagulation is important to prevent thrombosis. Furthermore, Bein et al.8 recently demonstrated that adding acetylsalicylic acid to heparin for anticoagulation management reduces thrombotic complications without bleeding. Addition of acetylsalicylic acid can also be considered as one of the techniques for prevention of thrombosis.

However, our cases show some limitations to the general hypothesis that low blood flow and stasis are the causes of thrombosis. In addition, reviews assessing coagulopathy with antithrombin III activity were not evaluated although underlying antithrombin III deficiency, which would cause heparin resistance, would be a possible cause of thrombosis. Therefore, if thrombotic events occur despite adequate anticoagulation, combined antithrombin III deficiency must be considered and evaluated9,10.

In conclusion, thrombotic complications are one of the common complications in iLA. A small-sized cannula may be beneficial in reducing limb ischemia but not thrombosis in low blood flow settings. The arterial diameter should be evaluated using Doppler ultrasound before insertion of the cannula. In patients with a small femoral artery, pump-driven venovenous ECMO should be considered as an alternative treatment. Also, strict target-achieved anticoagulation is important to prevent thrombosis.

Figures and Tables

Figure 2

Case 2. Chest spiral computed tomography scan showing filling defect at pulmonary artery (arrow).

Table 1

Patient demographic and clinical data

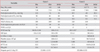

Table 2

Coagulation parameters, dose of heparin, changes in gas exchange, cardiovascular and respiratory variables before and during iLA treatment

Table 3

Comparison in coagulation parameters, dose of heparin, catheter size, and flow rate between thrombosis and non-thrombosis group of during iLA

References

1. Tao W, Brunston RL Jr, Bidani A, Pirtle P, Dy J, Cardenas VJ Jr, et al. Significant reduction in minute ventilation and peak inspiratory pressures with arteriovenous CO2 removal during severe respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 1997; 25:689–695.

2. Liebold A, Reng CM, Philipp A, Pfeifer M, Birnbaum DE. Pumpless extracorporeal lung assist: experience with the first 20 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000; 17:608–613.

3. Bein T, Weber F, Philipp A, Prasser C, Pfeifer M, Schmid FX, et al. A new pumpless extracorporeal interventional lung assist in critical hypoxemia/hypercapnia. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:1372–1377.

4. Zick G, Frerichs I, Schadler D, Schmitz G, Pulletz S, Cavus E, et al. Oxygenation effect of interventional lung assist in a lavage model of acute lung injury: a prospective experimental study. Crit Care. 2006; 10:R56.

5. Zimmermann M, Bein T, Arlt M, Philipp A, Rupprecht L, Mueller T, et al. Pumpless extracorporeal interventional lung assist in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective pilot study. Crit Care. 2009; 13:R10.

6. Jayroe JB, Wang D, Deyo DJ, Alpard SK, Bidani A, Zwischenberger JB. The effect of augmented hemodynamics on blood flow during arteriovenous carbon dioxide removal. ASAIO J. 2003; 49:30–34.

7. Cho WH, Lee K, Huh JW, Lim CM, Koh Y, Hong SB. Physiologic effect and safety of the pumpless extracorporeal interventional lung assist system in patients with acute respiratory failure: a pilot study. Artif Organs. 2012; 36:434–438.

8. Bein T, Zimmermann M, Philipp A, Ramming M, Sinner B, Schmid C, et al. Addition of acetylsalicylic acid to heparin for anticoagulation management during pumpless extracorporeal lung assist. ASAIO J. 2011; 57:164–168.

9. Villaneuva GB, Danishefsky I. Evidence for a heparin-induced conformational change on antithrombin III. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977; 74:803–809.

10. Oliver WC. Anticoagulation and coagulation management for ECMO. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009; 13:154–175.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download