Abstract

Here, we report a case of pleural paragonimiasis that was confused with tuberculous pleurisy. A 38-year-old man complained of a mild febrile sensation and pleuritic chest pain. Radiologic findings showed right pleural effusion with pleural thickening and subpleural consolidation. Adenosine deaminase (ADA) activity in the pleural effusion was elevated (85.3 IU/L), whereas other examinations for tuberculosis were negative. At this time, the patient started empirical anti-tuberculous treatment. Despite 2 months of treatment, the pleural effusion persisted, and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery was performed. Finally, the patient was diagnosed with pleural paragonimiasis based on the pathologic findings of chronic granulomatous inflammation containing Paragonimus eggs. This case suggested that pleural paragonimiasis should be considered when pleural effusion and elevated ADA levels are observed.

Pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis is a food-borne zoonosis commonly caused by the trematode Paragonimus westermani1. This parasitic infection has diverse symptoms and can mimic other conditions, such as mycobacterial infection or neoplasm2,3. Routine laboratory test results with pleural fluid examination and radiologic findings are non-specific for pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis, often delaying diagnosis4.

Lymphocytic pleural effusions, often caused by tuberculosis, are commonly encountered in clinical practice. The measurement of adenosine deaminase (ADA) levels can facilitate the diagnosis of tuberculous effusions, but false-positive findings from lymphocytic effusions have been reported5,6,7. Here, we report clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of a case that mimicked tuberculous pleurisy, but was ultimately diagnosed as pleural paragonimiasis after surgical biopsy.

A 38-year-old man developed right chest pain and dyspnea. He had been healthy until 12 months previously, when he developed right spontaneous pneumothorax. After drainage with a chest tube at a local hospital, the pneumothorax improved. He had no history of tuberculosis and the ingestion history of raw crab or river fish was uncertain.

One month before his visit to our hospital, the patient reported right chest pain and mild dyspnea. Three weeks later, a chest radiograph taken a local hospital revealed right pleural effusion. Serous fluid (400 mL) was removed and pleural fluid analysis showed that the white blood cell (WBC) count was 700/µL (67% lymphocytes) and the ADA level was 85.3 IU/L. The patient then started empirical anti-tuberculous treatment including isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. The patient was referred to our hospital because of persistent pleural effusion after 10 days of anti-tuberculous treatment.

Upon admission to our hospital, clinical laboratory testing showed that the blood leukocyte count was 8,600/µL, with a differential of 67.9% neutrophils and 5.2% eosinophils (normal range, 0-9.3%). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 120 mm/hr and the C-reactive protein level had increased to 8.27 mg/dL. A human immunodeficiency virus antibody test was negative. Chest radiography and computed tomography revealed right loculated pleural effusion with diffuse pleural thickening (Figure 1).

A percutaneous catheter was inserted and analysis of aspirated pleural fluid showed the following values: pH, 7.3; WBC count, 100/µL (69% polymorphonuclear neutrophils, 28% lymphocytes, 0% eosinophils); protein, 6.9 g/dL; lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 2,226 U/L (serum LDH, 246 U/L); glucose, 12 mg/dL; and ADA, 84 IU/L. The patient continued anti-tuberculous treatment. In addition, percutaneous catheter drainage of pleural fluid was performed with intrapleural urokinase instillation for 5 days. Despite these efforts, the loculated pleural effusion did not improve.

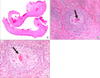

Therefore, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery was performed for decortication. Diffuse, dense fibrosis of the pleura and empyema sacs was observed. Adhesiolysis and decortication were the performed. Pathologic examination showed chronic granulomatous inflammation with parasitic eggs, many eosinophils, and necrosis, which were consistent with paragonimiasis (Figure 2). Parasite-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay after surgery was positive for Paragonimus. The patient was finally diagnosed with pleural paragonimiasis. Anti-tuberculous treatment was discontinued and praziquantel (25 mg/kg) was prescribed for 2 days. His symptoms and chest radiography were recovered 20 days after discharge. After 2 years of follow-up, the patient was free of symptoms and showed no pleural effusion on chest radiography.

Paragonimiasis is an infection caused by lung flukes, including Paragonimus westermani and related subspecies. Paragonimus is endemic in the Far East, including Korea, and in central South America and western Africa8. In these areas, reservoir hosts such as freshwater crab or crayfish harboring metacercariae of the parasite are an important source of human infection. When humans ingest pickled or inadequately cooked food, metacercariae reach the small intestine and excyst. They then penetrate the intestinal wall and enter the peritoneal cavity, migrate into the diaphragm, pleura, and reach the lung. Most patients are asymptomatic, but can present hemorrhage or inflammation causing necrosis and cysts9. Microscopic demonstration of eggs in stool or sputum and detection of antibodies to Paragonimus are important for diagnosis10,11. Surgical evaluation is also an important diagnostic option in complicated cases4.

Because pleural involvement of Paragonimus is a main presentation of pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis, the differentiation of this infection from other causes of pleural effusion is important12. Differentiation is especially important in tuberculosis-endemic areas because pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis is often difficult to distinguish from tuberculosis, leading to misdiagnosis. Although peripheral blood or pleural fluid eosinophilia is reported with a high incidence in patients with paragonimiasis, a small proportion of patients do not have these characteristic findings2,13. Our patient did not present with eosinophilia in the peripheral blood or eosinophils in pleural fluid and bronchoalveolar lavage. Ova or parasite bodies were not found in the bronchoalveolar lavage or stool. Furthermore, elevated ADA activity was suggestive of tuberculous pleurisy. Percutaneous drainage was ineffective, and the final diagnosis was delayed until surgical pleural biopsy, although the history of previous pneumothorax could suggest the possibility of paragnonimiasis.

ADA activity in pleural fluid is a useful biomarker of tuberculous pleurisy and provides a reliable basis for treatment decisions. However, high ADA levels can also be found in patients with other causes of pleural effusion5,6,7,14. Here, we report clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of a case that mimicked tuberculous pleurisy, but was diagnosed with pleural paragonimiasis after surgical biopsy. In conclusion, the possibility of pleural paragonimiasis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pleural effusion with elevated ADA levels in areas where tuberculosis and paragonimiasis could be prevalent.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Mukae H, Nawa Y. Paragonimiasis: a Japanese perspective. Clin Chest Med. 2002; 23:409–420.

2. Jeon K, Koh WJ, Kim H, Kwon OJ, Kim TS, Lee KS, et al. Clinical features of recently diagnosed pulmonary paragonimiasis in Korea. Chest. 2005; 128:1423–1430.

3. Song JU, Um SW, Koh WJ, Suh GY, Chung MP, Kim H, et al. Pulmonary paragonimiasis mimicking lung cancer in a tertiary referral centre in Korea. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011; 15:674–679.

4. Boland JM, Vaszar LT, Jones JL, Mathison BA, Rovzar MA, Colby TV, et al. Pleuropulmonary infection by Paragonimus westermani in the United States: a rare cause of eosinophilic pneumonia after ingestion of live crabs. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011; 35:707–713.

5. Lee YC, Rogers JT, Rodriguez RM, Miller KD, Light RW. Adenosine deaminase levels in nontuberculous lymphocytic pleural effusions. Chest. 2001; 120:356–361.

6. Jimenez Castro D, Diaz Nuevo G, Perez-Rodriguez E, Light RW. Diagnostic value of adenosine deaminase in nontuberculous lymphocytic pleural effusions. Eur Respir J. 2003; 21:220–224.

7. Krenke R, Korczynski P. Use of pleural fluid levels of adenosine deaminase and interferon gamma in the diagnosis of tuberculous pleuritis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010; 16:367–375.

8. Kagawa FT. Pulmonary paragonimiasis. Semin Respir Infect. 1997; 12:149–158.

9. Im JG, Whang HY, Kim WS, Han MC, Shim YS, Cho SY. Pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis: radiologic findings in 71 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992; 159:39–43.

10. Slemenda SB, Maddison SE, Jong EC, Moore DD. Diagnosis of paragonimiasis by immunoblot. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988; 39:469–471.

11. Xu ZB. Studies on clinical manifestations, diagnosis and control of paragonimiasis in China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1991; 22:Suppl. 345–348.

12. Vidamaly S, Choumlivong K, Keolouangkhot V, Vannavong N, Kanpittaya J, Strobel M. Paragonimiasis: a common cause of persistent pleural effusion in Lao PDR. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009; 103:1019–1023.

13. Taniguchi H, Mukae H, Matsumoto N, Tokojima M, Katoh S, Matsukura S, et al. Elevated IL-5 levels in pleural fluid of patients with paragonimiasis westermani. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001; 123:94–98.

14. Porcel JM, Esquerda A, Bielsa S. Diagnostic performance of adenosine deaminase activity in pleural fluid: a single-center experience with over 2100 consecutive patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2010; 21:419–423.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download