Abstract

Invasive aspergillosis has emerged as a major cause of life-threatening infections in immunocompromised patients. Recently, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, who have been receiving corticosteroids for a long period, and immunocompetent patients in the intensive care unit have been identified as nontraditional hosts at risk for invasive aspergillosis. Here, we report a case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis after influenza in an immunocompetent patient. The patient's symptoms were nonspecific, and the patient was unresponsive to treatments for pulmonary bacterial infection. Bronchoscopy revealed mucosa hyperemia, and wide, raised and cream-colored plaques throughout the trachea and both the main bronchi. Histologic examination revealed aspergillosis. The patient recovered quickly when treated systemically with voriconazole, although the reported mortality rates for aspergillosis are extremely high. This study showed that invasive aspergillosis should be considered in immunocompetent patients who are unresponsive to antibiotic treatments; further, early extensive use of all available diagnostic tools, especially bronchoscopy, is mandatory.

Invasive aspergillosis is known to have an important cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. However, during recent years, several reports have described a rising incidence of invasive aspergillosis in critically ill patients admitted to the intensive care unit, even in the absence of an apparent predisposing immunodeficiency. In this situation is related to difficulties in timely diagnosis, caused by insensitive and non-specific clinical signs and lack of unequivocal diagnostic criteria1.

After the 2009 A/H1N1 influenza pandemic, it has been shown that invasive aspergillosis is a much more frequent complication in critically ill H1N1 patients and that use of systemic steroids contribute to this superinfection2.

The authors report this case study, along with a literature review, which involves invasive pulmonary aspergillosis occurring after influenza infection in an immunocompetent patient who did not use systemic steroids.

A 60-year-old man was admitted chiefly with shortness of breath, pleural chest pain. The patient presented with fever, cough, and whitish sputum 10 days prior to consultation. Treatment was received from a local hospital for upper respiratory tract infection, but no improvements were observed. The patient was transferred to our hospital presenting with shortness of breath and pleural chest pain.

Underlying disease includes hypertension, and the patient has been taking medication for 20 years.

He was a non-smoker and did not have alcohol abuse history.

At the time of consultation, the blood pressure was 120/70 mm Hg; heart rate, 102 beats/min; respiratory rate, 24 breaths/min; and body temperature, 38.1℃. The patient was conscious but showed acute ill-looking appearance. Physical examination showed normal conjunctiva with no palpable lymph nodes around the neck. On auscultation of the chest, coarse breathing sounds without wheezing in both lower lung fields were heard. The abdomen was soft, and bowel sounds were normal; no hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were noted. Skin lesions were not observed.

In the peripheral blood test, leukocytes were 7,650/mm3 (neutrophils, 79.3%; lymphocytes, 12.3%; and eosinophils, 0.8%); hemoglobin, 14.9 g/dL; platelets, 124,000/mm3; and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 20 mm/hr (reference range, 0-20 mm/hr). C-reactive protein was 175 mg/dL (reference range, 0-3 mg/dL). In serum biochemistry, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine was 11.9/1.1 mg/dL; total protein/albumin, 6.3/3.6 g/dL; Ca/P, 7.7/2.7 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase, 43/36 IU/L; and total bilirubin, 0.83 mg/dL. For the hepatitis test in autoimmune serology screening, surface antigen of the hepatitis B virus and anti-hepatitis C virus were negative; anti-hepatitis B surface antigen was positive; in the thyroid function test results, T3 was 70.8 ng/dL (reference range, 58-159 ng/dL), whereas thyroid stimulating hormone was 0.701 µIU/mL (reference range, 0.35-4.94 IU/mL) and free T4 was 1.25 ng/dL (reference range, 0.7-1.48 ng/dL); and human immunodeficiency virus and venereal disease research laboratory results were negative. Serum level of IgA, IgG and IgM were within normal range. CD4 count was within normal. Although urinalysis did not show pyuria, microscopic hematuria and proteinuria were observed.

Chest radiography revealed focal consolidation in the right lower lung field, but no cardiomegaly.

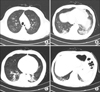

Multifocal ground glass opacities and peribronchial infiltration in both lungs were observed (Figure 1).

The patient presented shortness of breath and pleural chest pain. Chest radiographic findings showed focal consolidation in the lung. Therefore, ceftriaxone+azithromycin were administered since community-acquired pneumonia was suspected. However, fever persisted and hypoxia worsened, and thus, the medication was changed to piperacillin/tazobactam+levofloxacin. However, fever, worsening hypoxia (SpO2, 82.3%; PO2, 43.7 mm Hg), and chest radiographic findings worsened in addition to worsening of the leukocytosis (13,890/mm3). Since community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection was suspected, vancomycin was administered, and bronchoscopy was performed.

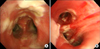

Diffuse mucosal hyperemia and wide, raised, and cream-colored plaques (pseudomembrane formation) were observed throughout the trachea and both main bronchi, without significant airway obstruction (Figure 2). Polymerase chain reaction test for influenza A from bronchoalveolar lavage was positive.

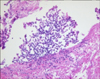

Numerous branching septate hyphae with acute angles less than 45° were observed (Figure 3).

The characteristic septate hyphae of Aspergillus were observed in biopsy. Voriconazole was administered, and the patient was discharged as improvements were observed in the patients fever, hypoxia (SpO2, 97.7%; PO2, 91.0 mm Hg), and leukocytosis (6,270/mm3). However, we were not able to further test for patient's financial reasons.

Aspergillus is widely distributed in the soil, and people normally inhale hundreds of spores daily, although healthy individuals are able to filter airborne fungi through the epithelial mucociliary defense mechanism and resident phagocyte actions3. Pulmonary aspergillosis is influenced by the immune status of the host and is categorized into aspergillosis species, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, chronic necrotizing aspergillosis, and invasive aspergillosis4. Among these, invasive aspergillosis typically occur in patients with seriously compromised immune system, which easily occurs in patients with hematologic malignancies, transplant recipients, and patients undergoing long-term steroid administration or with genetic immunodeficiency3. Tracheobronchial aspergillosis such as that described in this case study is an uncommon clinical form of invasive aspergillosis infection limited to the tracheobronchial tree5. In many cases of invasive aspergillosis patients, the observation of the halo sign in the initial chest CT scan helps initiate early treatment6; in the case of tracheobronchial aspergillosis, characteristic lesions are not observed in the chest radiographic and CT scans, and bronchoscopy may help by biopsy and characterization of the lesions7.

In the case of our patient, false membrane tracheobronchial aspergillosis was diagnosed, which is an advanced stage of disease that almost never occurs in people with normal immune system. Nonspecific symptoms include fever and cough, and wheezing occurs only when airways are obstructed by inflammation, mucus and fungal masses. Because of atypical clinical symptoms and radiological examination, diagnosis may be incorrect in the case of intensive care unit patients, but the characteristic lesions of bronchoscopy such as that described in this case study is the most sensitive diagnostic test8. The incidence of invasive aspergillosis has recently increased in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with long-term steroid administration and non-immunocompromised intensive care unit patients with very high mortality rate. The infection due to the influenza virus is caused by cell-mediated defects, disruption of normal ciliary clearance, and leukopenia, and these may be the leading factors of invasive fungal disease. Lat et al.9 repoted 2 patients with invasive aspergillosis after infection with pandemic (H1N1). They suggested that high-dose corticosteroids may be novel risk factors predisposing immunocompetent patients to invasive aspergillosis9. However, several reports have described invasive aspergillsosis occurring after influenza in a normal immune patients who has not received systemic steroids treatment. Hasejiima et al.10 reported a case of invasive aspergillosis, which was associated with influenza B.

Voriconazole is recommended as initial therapy in the treatment of tracheobronchial aspergillosis11. Multi-drug combination therapy can also be considered because effective outcomes have been shown12, although there is lack of evidence with respect to large-scale studies1.

For ICU patients with normal immune system, bronchoscopy is necessary for early diagnosis, when patients do not respond to common antibiotics and when invasive aspergillosis may be the leading causative factor.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1(A-D) Chest computed tomography findings. Multifocal ground glass opacities and peribronchial infiltration in both the lungs. |

References

1. Trof RJ, Beishuizen A, Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Girbes AR, Groeneveld AB. Management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in non-neutropenic critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2007; 33:1694–1703.

2. Wauters J, Baar I, Meersseman P, Meersseman W, Dams K, De Paep R, et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is a frequent complication of critically ill H1N1 patients: a retrospective study. Intensive Care Med. 2012; 38:1761–1768.

3. Lass-Flörl C, Roilides E, Loffler J, Wilflingseder D, Romani L. Minireview: host defence in invasive aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2013; 56:403–413.

4. Xu XY, Sun HM, Zhao BL, Shi Y. Diagnosis of airway-invasive pulmonary aspergillosis by tree-in-bud sign in an immunocompetent patient: case report and literature review. J Mycol Med. 2013; 23:64–69.

5. Lee HY, Kang HH, Kang JY, Kim SK, Lee SH, Chung YY, et al. A case of tracheobronchial aspergillosis resolved spontaneously in an immunocompetent host. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2012; 73:278–281.

6. Greene RE, Schlamm HT, Oestmann JW, Stark P, Durand C, Lortholary O, et al. Imaging findings in acute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: clinical significance of the halo sign. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 44:373–379.

7. Buchheidt D, Weiss A, Reiter S, Hartung G, Hehlmann R. Pseudomembranous tracheobronchial aspergillosis: a rare manifestation of invasive aspergillosis in a non-neutropenic patient with Hodgkin's disease. Mycoses. 2003; 46:51–55.

8. Tasci S, Glasmacher A, Lentini S, Tschubel K, Ewig S, Molitor E, et al. Pseudomembranous and obstructive Aspergillus tracheobronchitis: optimal diagnostic strategy and outcome. Mycoses. 2006; 49:37–42.

9. Lat A, Bhadelia N, Miko B, Furuya EY, Thompson GR 3rd. Invasive aspergillosis after pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16:971–973.

10. Hasejima N, Yamato K, Takezawa S, Kobayashi H, Kadoyama C. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis associated with influenza B. Respirology. 2005; 10:116–119.

11. Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, et al. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 46:327–360.

12. De Rosa FG, Terragni P, Pasero D, Trompeo AC, Urbino R, Barbui A, et al. Combination antifungal treatment of pseudomembranous tracheobronchial invasive aspergillosis: a case report. Intensive Care Med. 2009; 35:1641–1643.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download