Abstract

A 61-year-old woman came to the hospital with dyspnea and pleural effusion on chest radiography. She underwent repeated thoracentesis, transbronchial lung biopsy, bronchoalveolar lavage, and thoracoscopic pleural biopsy with talc pleurodesis, but diagnosis of her was uncertain. Positron emission tomography showed multiple lymphadenopathies, so she underwent endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph nodes. Here, we report a case of malignant pleural mesothelioma that was eventually diagnosed by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. This is an unusual and first case in Korea.

Malignant pleural mesothelioma is an aggressive, treatment-resistant, and universally fatal disease1. Diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma is quite difficult2. For the definite diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is necessary2. But VATS is often impossible in some conditions3. Here, we report the case of a patient with malignant pleural mesothelioma that was not diagnosed by other modalities and was eventually diagnosed by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA).

A 61-year-old woman presented with pleural effusion and recurrent pneumothorax. She underwent repeated thoracentesis, transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB), bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and thoracoscopic pleural biopsy with talc pleurodesis. However, all examinations were non-diagnostic. VATS biopsy was considered but was not performed because of pleural adhesion.

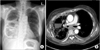

She was admitted to our hospital because her respiratory symptoms did not improve. Chest radiography (CXR) and chest computed tomography (CT) revealed multifocal air-fluid levels, consolidation, and pleural thickness (Figure 1). Positron emission tomography (PET) showed hyper-metabolic lesions in right upper paratracheal, right lower paratracheal, subcarinal, and right interlobar lymph nodes (Figure 2).

EBUS-TBNA was performed to obtain a tissue specimen for diagnosis of disease. Adequate tissue was obtained by 3 aspirations from the right upper paratracheal lymph node (#2R), 2 aspirations from the subcarinal lymph node (#7), and 3 aspirations from the right interlobar lymph node (#11R) (Figure 2).

Pathologically, the tumor cells obtained from EBUS-TBNA procedure showed dominant papillary architecture (Figure 3A, B). Nevertheless, at cytology smear, tumor cells were relatively dyscohesive and demonstrated narrow windows (figure not shown). Pathologic differential diagnoses were malignant mesothelioma and pulmonary adenocarcinoma. By immunohistochemical stainings, tumor cells were strongly labeled for anti-calretinin antibody both in cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure 3C). Positive reactions for anti-cytokeratin 5/6 (Figure 3E) and anti-Wilms tumor 1 (Figure 3F) antibodies were also noted. Nevertheless, immunohistochemical staining for anti-thyroid transcription factor-1 antibody was negative (Figure 3D), consistent with malignant mesothelioma rather than pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

PET findings showed multiple lymphadenopathies in both supraclavicular areas (N3 lymph node). Her clinical stage was IV. Two weeks after the diagnosis, she received premetrexed/cisplatin chemotherapy.

Chest CT is the widely used modality for evaluation of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Common chest CT findings are pleural effusion with focal pleural thickening in the early stage and large mass or circumferential tumors in the late stage. Most patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma present at an advanced stage at time of diagnosis4. Metastasis is frequently found at post mortem, and common sites of spread are the hilar, mediastinal, internal mammary, and supraclavicular lymph nodes1.

As with other cancers, obtaining of the appropriate tissue is important for diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Because endobronchial lesions are rarely seen in mesothelioma, bronchofibroscopy is not helpful. Thoracentesis and closed pleural biopsy can be tried, but they do not provide enough tissue to confirm the diagnosis. Sensitivity of fluid cytology by thoracentesis alone was only 26%, and pleural biopsy was 44%5,6. To accurately diagnose malignant pleural mesothelioma, thoracoscopic biopsy is recommended. In one study, diagnosis was achieved in 98% of patients7.

Thoracoscopic biopsy is often impossible (fused lung, marked unstable patient, and partial or complete unilateral collapse of the lung) and dangerous (prolonged air leak, pulmonary atelectasis, respiratory failure, and seeding)3,8. Our patient underwent thoracoscopic talc pleurodesis with pleural biopsy because of recurrent pneumothorax, and she could not undergo VATS. So, we performed EBUS-TBNA, and finally diagnosed her condition as malignant pleural mesothelioma.

The pathologic diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma cannot be easily rendered in this case because of predominantly papillary pattern, which can also be seen in other adenocarcinomas9. In this case, positivity for anti-calretinin and anti-cytokeratin 5/6 were helpful for the diagnosis of mesothelioma. There were convincing evidences that cytoplasmic and nuclear stainings for calretinin were largely observed in malignant mesotheliomas, but not in other adenocarcinomas10,11. Positive reactions for cytokeratin 5/6 also suggested mesothelioma12.

Although there are reports of diagnosis and staging of malignant pleural mesothelioma by EBUS-TBNA, this is the first case that was diagnosed by EBUS-TBNA when VATS was impossible, after failing diagnosis by thoracentesis, TBLB, BAL, and thoracoscopic pleural biopsy13,14. In addition, this is first case that was diagnosed as malignant pleural mesothelioma by EBUS-TBNA in Korea.

In summary, one female patient was admitted because of pleural disease with unknown etiology. She underwent usual examinations, CXR, chest CT, PET, thoracentesis, thoracoscopic biopsy, bronchofibroscopy with BAL and TBLB. But all examinations were non-diagnostic. We considered VATS, but she could not undergo it because of pleural adhesion. She had multiple mediastinal lymph nodes on PET, so she underwent EBUS-TBNA and was finally diagnosed as malignant pleural mesothelioma. It is an unusual case, so we report it.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

Multiple air-fluid levels and consolidation were seen on chest radiography (A) and chest computed tomography (B).

Figure 2

Positron emission tomography computed tomography showed multiple high uptake lesions, and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration was done on right upper paratracheal (A, D), subcarinal (B, E), and right interlobar (C, F) lymph nodes.

Figure 3

Pathologic findings obtained by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Papillary clusters of epithelioid cells (H&E stain, A, ×100; B, ×400), positive for anti-calretinin antibody (C, ×400), negative for anti-thyroid transcription factor-1 antibody (D, ×400), positive for cytokeratin 5/6 (E, ×400) and weak, but definitive Wilms tumor 1 (F, ×400).

References

1. Robinson BW, Musk AW, Lake RA. Malignant mesothelioma. Lancet. 2005. 366:397–408.

2. Suzuki K. Diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma: thoracoscopic biopsy and tumor marker. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2009. 110:333–337.

3. Dieter RA Jr, Kuzycz GB. Complications and contraindications of thoracoscopy. Int Surg. 1997. 82:232–239.

4. Renshaw AA, Dean BR, Antman KH, Sugarbaker DJ, Cibas ES. The role of cytologic evaluation of pleural fluid in the diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma. Chest. 1997. 111:106–109.

5. Campbell NP, Kindler HL. Update on malignant pleural mesothelioma. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011. 32:102–110.

6. McLaughlin KM, Kerr KM, Currie GP. Closed pleural biopsy to diagnose mesothelioma: dead or alive? Lung Cancer. 2009. 65:388–389.

7. Boutin C, Rey F. Thoracoscopy in pleural malignant mesothelioma: a prospective study of 188 consecutive patients. Part 1: Diagnosis. Cancer. 1993. 72:389–393.

8. Agarwal PP, Seely JM, Matzinger FR, MacRae RM, Peterson RA, Maziak DE, et al. Pleural mesothelioma: sensitivity and incidence of needle track seeding after image-guided biopsy versus surgical biopsy. Radiology. 2006. 241:589–594.

9. Kawai T, Greenberg SD, Truong LD, Mattioli CA, Klima M, Titus JL. Differences in lectin binding of malignant pleural mesothelioma and adenocarcinoma of the lung. Am J Pathol. 1988. 130:401–410.

10. Ordonez NG. Value of calretinin immunostaining in differentiating epithelial mesothelioma from lung adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 1998. 11:929–933.

11. Chhieng DC, Yee H, Schaefer D, Cangiarella JF, Jagirdar J, Chiriboga LA, et al. Calretinin staining pattern aids in the differentiation of mesothelioma from adenocarcinoma in serous effusions. Cancer. 2000. 90:194–200.

12. Ordonez NG. Value of cytokeratin 5/6 immunostaining in distinguishing epithelial mesothelioma of the pleura from lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998. 22:1215–1221.

13. Hamamoto J, Notsute D, Tokunaga K, Sasaki J, Kojima K, Saeki S, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration in a case with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Intern Med. 2010. 49:423–426.

14. Rice DC, Steliga MA, Stewart J, Eapen G, Jimenez CA, Lee JH, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for staging of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009. 88:862–868.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download