This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) has been considered to be a precursor lesion of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) and pulmonary adenocarcinoma. It usually coexists with BAC and/or an adenocarcinoma. Chest computed tomography reveals multiple well-defined nodules with ground-glass opacity. Usually, AAH does not exceed 10 mm in size. AAH with extensive involvement on one side of the lung field or one that is larger than 2 cm has not been previously reported. We herein report a case of a 71-year-old nonsmoking female with lung AAH of larger than 2 cm.

Go to :

Keywords: Lung, Precancerous Conditions, Adenocarcinoma

Introduction

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) is pathologically defined as lesion of atypical cells resembling type 2 alveolar cell or cubic cell proliferation usually less than 5 mm in diameter

1. In 1999, World Health Organization reported that AAH is included in precursor lesions of lung cancer along with squamous dysplasial carcinoma

in situ, and diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia

1. Most studies have not been able to find the direct association of malignant tumors and AAH. Instead AAH is explained as a precursor lesion, especially of adenocarcinoma, connecting with the low frequency in noncancerous lung

2. Reports tell that the AAH chest computed tomography (CT) finding shows nodular ground-glass opacity (GGO) pattern

3,

4. AAH cases reported until today also report that it is only scattered in local lesion.

In this paper, we report a 71-year-old female who was diagnosed with lung AAH of larger than 2 cm that was distributed diffusely in the right lobe. She had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis and suffered from dyspnea on exertion showing extensive invasion in the right lung.

Go to :

Case Report

A 71-year-old female visited the outpatient department with a 2-week history of coughing with sputum and dyspnea on exertion. She had no other medical history with the exception of pulmonary tuberculosis at the age of 30 years. After administration of anti-tuberculosis medication, she was completely cured.

A chest X-ray performed during the patient's first visit to the outpatient department showed consolidation in the right lower lung field and focal consolidation in the left lower lobe. Sputum acid-fast bacteria (AFB) staining was negative. On bronchoscopy, the inlet of the right lower lobe was crushed out, especially the superior segment of the lower lobe. However, intraluminal lesions were not found. Based on these results, the patient was diagnosed with community-acquired pneumonia and was prescribed clarithromycin for 7 days. She was scheduled for a follow-up chest X-ray after finishing the medication, but she did not return to the hospital.

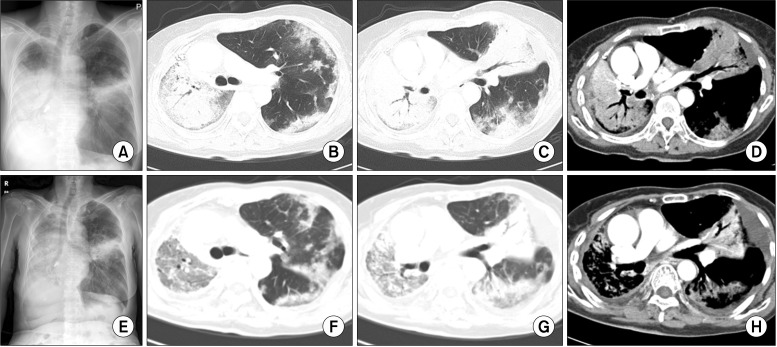

The patient returned to the hospital after 6 months because of dyspnea on exertion (American Thoracic Society grade 2). A chest X-ray was again performed (

Figure 1A). The right middle lobe and lower lobe showed increased haziness and density together with linear consolidation in the left lung. A chest CT scan was then performed (

Figure 1B-D). Consolidation was seen in all right lung zones with the exception of the superior segment of the right upper lobe. The right middle and lower lobes were mainly collapsed. Both the upper lobe and left lower lobe had many nodules. They also showed GGOs. Compared with the first chest X-ray, increases in the extent and haziness of the lesions were observed. Therefore, due to suspicion of pneumonia aggravation, we administered cefepime and clindamycin after performing a culture. However, we could not rule out the possibility of pulmonary tuberculosis reactivation or a cancerous mimic of pneumonia. Therefore, sputum AFB staining and cytology were performed, followed by bronchoscopy. Transbronchial lung biopsy was attempted, but failed. The AFB stain and cytology tests were all negative, and there was no endobronchial mucosal lesion. Upon admission, vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 100/60 mm Hg, heart rate 114 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20/min, and body temperature 39.1℃. The patient was alert and oriented, but showed an acutely ill-looking appearance, and there were rales in the right lower lobe zone with a rough respiratory sound.

| Figure 1Chest posteroanterior (PA) view and chest computed tomography (CT). (A) Chest PA on first admission. Patient revisited for aggravation of dyspnea on exertion. Widening of haziness in the right lower lung field and aggravation of linear infiltration in the left middle lung field were shown. (B-D) Chest CT on first admission. Airspace consolidation in the right lung and lingular division of the left upper lobe were shown on the CT. Collapse of the right middle lobe and right lower lobe was noted. Multiple variably sized nodules, some well-defined and some ill-defined, with patchy consolidation and ground-glass opacity (GGO) are present in both the upper lobe and left lower lobe (LLL). (E) Chest PA on second admission. (F-H) Improvement of consolidation in the right lung field, but increased extent of GGO in the right upper lobe and LLL were noted on chest CT at the second admission.

|

Peripheral blood test results were as follows: white blood cells 25,200/µL (neutrophils 86%, lymphocytes 7.3%, monocytes 6.1%, eosinophils 0.5%, and basophils 0.3%), hemoglobin 14.6 g/dL, and platelets 205,000/µL. In addition, the C-reactive protein level increased to 6.6 mg/dL. Chemistry test results were as follows: aspartate aminotransferase 20 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 15 IU/L, total bilirubin 1.4 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase 440 IU/L, total protein 7.1 g/dL, albumin 3.8 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen 12 mg/dL, and creatinine 0.6 mg/dL. The results of arterial blood gas analysis at room temperature were as follows: pH 7.46, pCO2 31 mm Hg, pO2 67 mm Hg, HCO3 22 mmol/L, and saturation 94%. There was no improvement on chest X-ray after finishing the antibiotics or after changing them. The bronchoscopic washing cytology test results obtained before admission were suspicious for malignancy. Thus, a peripheral blood carcinoembryonic antigen level was obtained, and the result was 0.8 ng/mL.

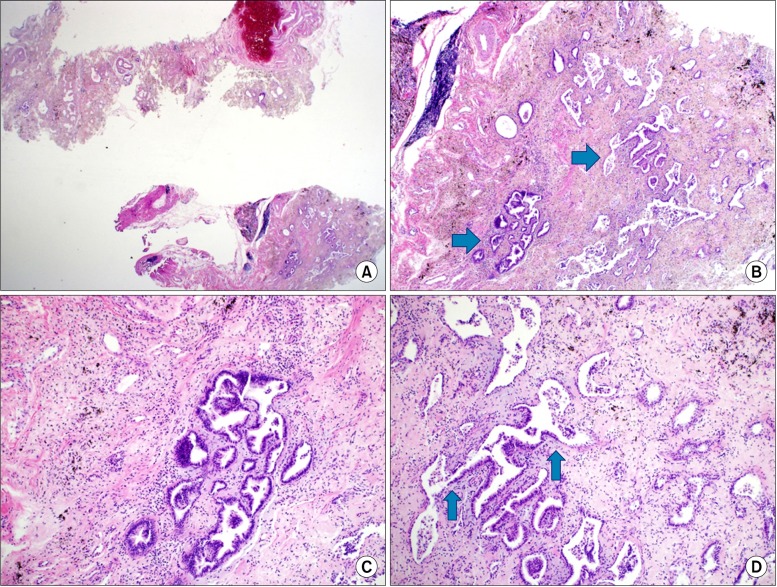

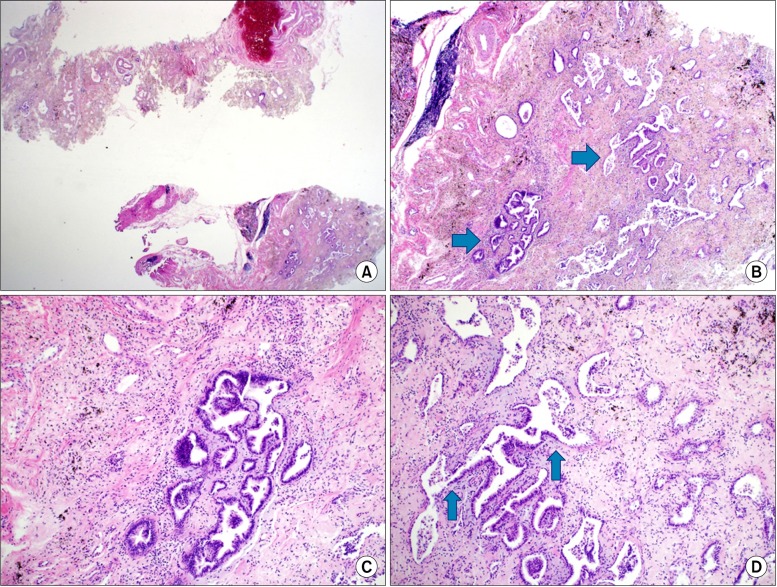

For a definitive diagnosis, an open lung biopsy was performed in the basal segment of the right lower lobe. The lesion in the right lobe showed a homogenous nodular pattern during the surgery, and the biopsy was extracted from the right basal segment. A 2.5×1.7-cm section of tissue was extracted for frozen biopsy and was diagnosed as AAH (

Figure 2). Regular biopsy using the rest of the tissue after frozen biopsy revealed AAH with a negative epidermal growth factor receptor (

EGFR) mutation test. The blood and sputum cultures upon admission were both negative, as was the AFB culture of sputum. The patient's fever and other symptoms showed improvement after 26 days of hospitalization with supportive care. The patient was then finally discharged.

| Figure 2Pathologic findings of the surgical lung biopsy specimen and microscopic findings upon hematoxylin and eosin staining. (A) Overall fibrosis and focal atypical alveolar epithelium are noted. (B) Atypical alveolar epithelium (arrows). (C) Magnified atypical alveolar epithelium. (D) Transition area from normal to atypical alveolar epithelium (arrows).

|

After 4 months, the patient was admitted again due to aggravated dyspnea on exertion. Both a chest X-ray (

Figure 1E) and CT scan (

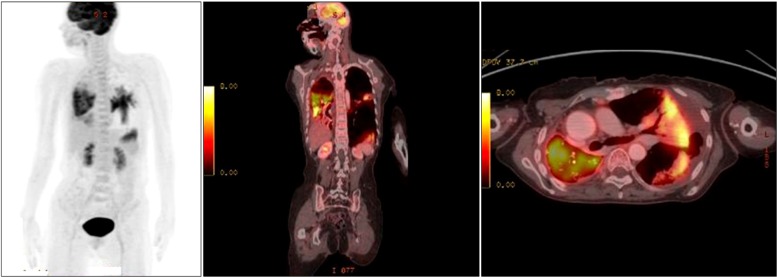

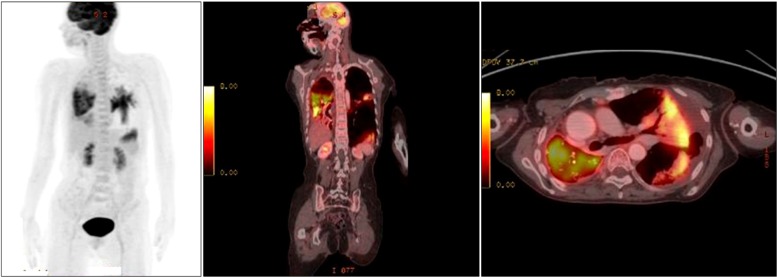

Figure 1F-H) were performed. On the chest CT scans, the right lung consolidation was improved, but the extent of the GGO had increased. In the lateral segment and posterior basal segment of the left lower lobe, the GGO pattern as well as the extent and haziness of the consolidation had increased. Moreover, the size of the multiple nodules with GGO increased. Thus, the patient was diagnosed with AAH in progression. According to these findings, positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) was performed to rule out malignancy and in preparation for possible chemotherapy. PET-CT was performed on the first day. The images in

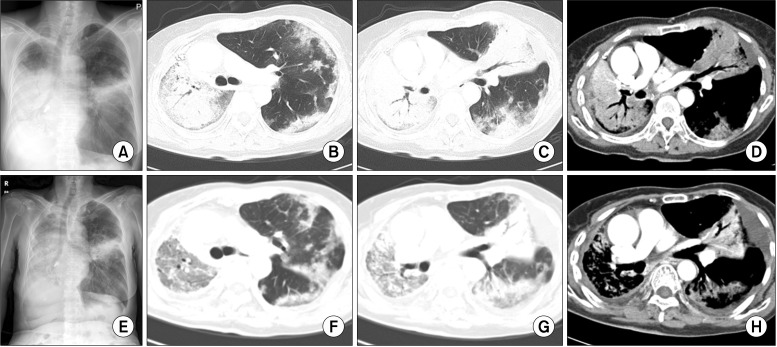

Figure 3 show that there was some glucose uptake in the lesions in the collapsed part of the right lower lobe, but no uptake in the regional lymph nodes. These observations were believed to be secondary to an infection rather than a cancerous lesion. The biopsy results were consistent with AAH. Gefitinib was administered to the patient after 7 days of hospitalization. After 17 days of treatment with gefitinib, a follow-up chest X-ray was performed.

Figure 4 shows that the right lung and hazy left lower lobe consolidation had improved compared with the findings before gefitinib treatment.

| Figure 3Increased glucose metabolism in the right middle and lower lung zones and lateral and posterobasal segment of the left lower lobe are shown using positron emission tomography-computed tomography.

|

| Figure 4Chest radiograph in 17 days after gefitinib treatment.

|

Go to :

Discussion

In South Korea, cancer is the most common cause of death, with lung cancer mortality being the highest

5. Therefore, early diagnosis with close observation related to lung cancer and its precursor lesions is important to decrease the lung cancer mortality and prevalence.

Ishikawa et al.

6 analyzed retrospectively 36 AAH lesions of less than 5 mm on CT. Thirty-five lesions showed a GGO pattern with no enhancement. In another study

7, three of seven patients with AAH had multifocal AAH. All AAH lesions were round or oval in shape with a GGO pattern. Based on these studies, patients with AAH show a GGO pattern on chest CT scans.

There is no definite AAH size standard. However, a previous study showed that the largest AAH is about 5 mm

8. In South Korea, a total of three AAH cases have been reported. In a study performed by Bae et al.

9, AAH nodules smaller than 5 mm accompanied by adenocarcinoma were found in the left upper lobe (n=1), left lower lobe (n=2-3), and right upper lobe or lower lobe (n=10). A similar case involving a 5-mm GGO lesion without adenocarcinoma was reported in 2007

10. In 2009, another case report described an AAH lesion of smaller than 5 mm that showed a GGO pattern accompanied by lung congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation

11. In other countries, multiple AAH lesions of up to 10 mm scattered in both lung fields have been reported

12. Another case report described a 16-mm AAH lesion accompanied by adenocarcinoma

13. In Italy, an AAH lesion with BAC of the lung was reported as a 20-mm GGO lesion

14. It is difficult to prove, however, if this was the largest AAH lesion reported because there was no mention of whether the lesion arose from BAC or AAH. Thus, to date, there has been no reported AAH lesion of larger than 16 mm. In the present case, the lesion invaded both lungs and was distributed diffusely, so extracting a biopsy sample from all portions of the lesion was difficult. Therefore, we cannot conclude that all of the lesion comprised AAH. However, considering that the maximum size of AAH was 16 mm in the above-mentioned study, and that the size of the tissue by open lung biopsy in the present study was 2.5×1.7 cm, this case is meaningful in that the size of AAH may be larger than 2 cm. We believed that the non-biopsied lesion was not infectious because it did not improve with antibiotics and no microorganisms were revealed upon culture; however, improvement was seen with gefitinib. In addition, the morphology of the lesion as seen during the surgery was homogenous; thus, it may have been identical to that extracted for biopsy. Therefore, there is a possibility that AAH extensively involved the right lung.

The most common disease associated with AAH is cancer, with adenocarcinoma showing a 23% prevalence

2. In addition, AAH is associated with BAC

15 and congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation

11. There are also cases in which AAH is not associated with other diseases

10,

12. We cannot exclude the possibility that the non-biopsied lesion in this case was accompanied with adenocarcinoma. However, one case

14 in 2009 described a patient with disseminated AAH with EGFR and K-ras-negative results who was completely cured by a 12-month course of gefitinib. The lesions in both lungs in this case improved with gefitinib; therefore, all may have been AAH with no adenocarcinoma.

There have been no reports of AAH lesions scattered broadly in one lung, as in this case. Therefore, this finding of disseminated consolidation of more than 2 cm can be one of the radiologic findings of AAH not only GGO of less than 10 mm what we have known, meanwhile.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download