Abstract

Inhalation of toxic gases can lead to pneumonitis. It has been known that methane gas intoxication causes loss of consciousness or asphyxia. There is, however, a paucity of information about acute pulmonary toxicity from methane gas inhalation. A 21-year-old man was presented with respiratory distress after an accidental exposure to methane gas for one minute. He came in with a drowsy mentality and hypoxemia. Mechanical ventilation was applied immediately. The patient's symptoms and chest radiographic findings were consistent with acute pneumonitis. He recovered spontaneously and was discharged after 5 days without other specific treatment. His pulmonary function test, 4 days after methane gas exposure, revealed a restrictive ventilatory defect. In conclusion, acute pulmonary injury can occur with a restrictive ventilator defect after a short exposure to methane gas. The lung injury was spontaneously resolved without any significant sequela.

Methane is a component of natural gas, mainly used as a fuel source and chemical feedstock in industries. It is usually harmless, however, at high concentrations, it may reduce the oxygen percentage in air, causing suffocation. It is also extremely flammable and can cause an explosion when its concentration reaches 5% to 15% in air. Previous reports focused mainly on accidents involving workers in coal mines that related to asphyxia or methane gas explosions1-3. In this report, we described the first case of acute pulmonary toxicity from accidental inhalation of methane in a medical gas supply room.

A 21-year-old man, non-smoker, was admitted to the emergency department (ED) in a drowsy mentality after exposure to methane gas. He had started working at a medical gas supply company 3 months ago. He had worked without any respiratory protective devices. While opening a methane gas tank, assuming it was a nitrogen tank, he was accidently exposed in a gas supply room, approximately 10×10 m. There was no window and the doors were kept closed in the room. When the methane tank was opened, gas escaped from the tank for about one minute. Immediately after exposure, he sought refuge in a room inside of the gas supply space and soon lost consciousness. Approximately, 4.5 hours after exposure he was admitted to the ED.

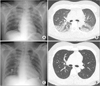

When he arrived at the ED, his vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 160/100 mm Hg; heart rate, 130 beats/min; respiratory rate, 28 breaths/min; temperature, 36.2℃; and O2 saturation measured by pulse oxymeter (SpO2), 75% of room air. His oropharynx was found to be normal. There was a bilateral decrease in breathing sounds without wheezing, stridor or crackles on pulmonary auscultation. He was immediately intubated because he was cyanotic and in respiratory distress. Initial blood gas during intubation with 10 L/min oxygen supply showed pH 7.268, PCO2 34.5 mm Hg, PO2 77.2 mm Hg, HCO3- 15.3 mmol/L, and SaO2 93.3%. Electrocardiography showed sinus tachycardia. Serum blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and lactate were 11 mg/dL, 0.8 mg/dL, and 14.0 mmol/L, respectively. Initial chest radiograph showed bilateral ill-defined air-space consolidations on both perihilar areas, which mimics pulmonary edema but heart and great vessels appeared unremarkable (Figure 1A). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed bilateral symmetric air-space consolidation and ground glass opacity at the dependent portion of the lungs (Figure 1B). After mechanical ventilation (MV) with fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 0.6, his SpO2 increased to 98%. Four hours after MV he gained an alert mentality. Subsequent blood gas analysis showed a pH 7.36, PCO2 34.5 mm Hg, PO2 77 mm Hg, HCO3- 15.3 mmol/L, and SaO2 95.0% under MV (synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation; SIMV; FiO2 of 0.4). He received albuterol nebulizer treatment. Peripheral blood tests showed the following: white blood cells, 14,550/mm3 (neutrophils, 36%; lymphocytes, 58%; and eosinophils, 2%); hemoglobin, 15.9 g/dL; and platelets, 296,000/mm3. Four hours after arriving at the ED, he was weaned from MV to 4 L/min nasal cannula with SpO2 96%. The next day, a chest radiograph showed resolution of bilateral airspace consolidations (Figure 1C). He was admitted to the intensive care unit for 24 hours and subsequently transferred to the general ward when oxygen was no longer required. A pulmonary function test was performed 4 days after exposure. The results were as follows: forced vital capacity (FVC), 3.3 L (68% predicted); forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), 3.0 L (74% predicted); FEV1 to FVC ratio, 90%; and total lung capacity, 4.2 L (70% predicted). A single-breath carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLco) was 24.5 mL/min/mm Hg (83% predicted). His symptoms resolved and he was discharged after 5 days without medication. Ten days after discharge, the follow-up chest CT scan showed a complete resolution of previous bilateral air-space consolidations (Figure 1D). The follow-up pulmonary function test showed recovery from the restrictive ventilatory defect.

There are several reports focused on occupational methane gas exposure by asphyxia or burns1-3. The first incidents happened accidently to coal mine workers and later to farmers after manure gas intoxication4,5. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of acute pulmonary toxicity related to methane gas inhalation. In this case report, we highlight that even a short exposure time to a high concentration of methane gas can be sufficient to cause a serious problem.

Usually methane is not harmful; however, it can cause asphyxiation by reducing the percentage of O2 in a sealed room. This may explain the reason why the patient lost consciousness. The case exposed methane gas accidentally in a medical gas supply room. Even a 1-minute exposure to a high concentration of methane gas in a sealed room was enough to cause loss of consciousness. There was a case report that describes induced hypothermia used as a treatment for comatose state in a patient with asphyxia caused gas intoxication including methane6. However, there was no established treatment for methane intoxication.

Acute restrictive ventilator defect with reduced DLco was found in a patient with heavy occupational exposure to fluorocarbon7. In the present case, we found a restrictive defect without changes in DLco on the fourth day after exposure. During recovery phase of lung injury, there is an increase in collagenous/elastic fibers causing restrictive ventilator pattern in the name of organizing pneumonia8. The restrictive pattern in pulmonary function test in the present case supported the patient might have organizing pneumonia during recovery phase. Our patient is a young non-smoker without a history of lung disease. The real pathogenesis is not clear; however, we suggest that methane intoxication may develop reversible toxic alveolitis based on radiologic findings. However, direct pulmonary toxicity from inhalant abuse is rarely reported9.

This case demonstrates that acute lung injury can occur following short exposure to high concentrations of methane gas in closed places. Acute pulmonary injury can occur with a restrictive ventilator defect. The lung injury can be spontaneously resolved without any significant sequela.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

Representative chest radiographs. (A) Chest radiograph: 4.5 hours following exposure. Initial chest radiograph shows bilateral ill-defined air-space consolidations at both perihilar areas. (B) Chest computed tomography (CT) scan at emergency department shows bilateral symmetric air-space consolidations and ground glass opacities at dependent portion of both lungs. (C) Chest radiograph: 24 hours following exposure. There is a rapid resolution of bilateral air-space consolidations on follow-up chest radiograph. (D) Follow-up chest CT scan shows no bilateral symmetric air-space consolidations and ground glass opacities without sequela.

References

1. Byard RW, Wilson GW. Death scene gas analysis in suspected methane asphyxia. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1992. 13:69–71.

2. Terazawa K, Takatori T, Tomii S, Nakano K. Methane asphyxia: coal mine accident investigation of distribution of gas. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1985. 6:211–214.

3. Kucuker H. Occupational fatalities among coal mine workers in Zonguldak, Turkey, 1994-2003. Occup Med (Lond). 2006. 56:144–146.

4. Knoblauch A, Steiner B. Major accidents related to manure: a case series from Switzerland. Int J Occup Environ Health. 1999. 5:177–186.

5. Beaver RL, Field WE. Summary of documented fatalities in livestock manure storage and handling facilities: 1975-2004. J Agromedicine. 2007. 12:3–23.

6. Baldursdottir S, Sigvaldason K, Karason S, Valsson F, Sigurdsson GH. Induced hypothermia in comatose survivors of asphyxia: a case series of 14 consecutive cases. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010. 54:821–826.

7. Wallace GM, Brown PH. Horse rug lung: toxic pneumonitis due to fluorocarbon inhalation. Occup Environ Med. 2005. 62:414–416.

8. Parra ER, Noleto GS, Tinoco LJ, Capelozzi VL. Immunophenotyping and remodeling process in small airways of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: functional and prognostic significance. Clin Respir J. 2008. 2:227–238.

9. Weibrecht KW, Rhyee SH. Acute respiratory distress associated with inhaled hydrocarbon. Am J Ind Med. 2011. 54:911–914.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download