Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of chronic morbidity and mortality throughout the world and is the only major disease that is continuing to increase in both prevalence and mortality. The second Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey revealed that the prevalence of COPD in Korean subjects aged ≥45 years was 17.2% in 2001. Further surveys on the prevalence of COPD were not available until 2007. Here, we report the prevalence of spirometrically detected COPD in Korea, using data from the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey (KNHANES IV) which was conducted in 2007~2009.

Methods

Based on the Korean Statistical Office census that used nationwide stratified random sampling, 10,523 subjects aged ≥40 years underwent spirometry. Place of residence, levels of education, income, and smoking status, as well as other results from a COPD survey questionnaire were also assessed.

Results

The prevalence of COPD (defined as forced expiratory volume in 1 sec/forced vital capacity <0.7 in subjects aged ≥40 years) was 12.9% (men, 18.7%; women, 7.5%). In total, 96.5% of patients with COPD had mild-to-moderate disease; only 2.5% had been diagnosed by physicians, and only 1.7% had been treated. The independent risk factors for COPD were smoking, advanced age, and male gender.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major disease which is continuing to increase in prevalence and mortality rate, worldwide1-5. In Korea, COPD ranked 6th among the causes of death in 20086. Moreover, the hospitalization cost associated with COPD increased from 111 billion won in 2004 to 266 billion won in 2008. Therefore, COPD imposes a great burden on the public health7.

The worldwide prevalence of COPD has been estimated to be 7.5~10%8. In a nationwide COPD prevalence survey in Korea in conjunction with the second South Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Korean NHANES II) conducted 2001, 17.2% of Korean adults over the age of 45 years had COPD9. However, there was no follow-up survey until 2007. The Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases and the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention conducted a survey on national health and nutrition, including assessment of COPD prevalence, beginning in 2007. Here, we report on the prevalence of COPD in Korea, using data from the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV).

Unlike previous surveys as short-term ones for 2~3 months at an interval of three years, KNHANES IV (2007~2009) was performed as a survey all year around. The KNHANES IV used rolling sampling survey method for the sample in each year to present the whole nation and to be similar by years.

KNHANES IV investigated 4,600 households from 200 enumeration districts per year (23 households per enumeration district) with the data of Population and Housing Census conducted by Statistics Korea as a tool for sampling. Enumeration districts were obtained by classifying the whole nation into 11 regions (seven metropolitan cities; Gyeonggi, Gyeongsang/Gangwon, Chungcheong, Jeolla/Jeju) and they were stratified into 29 regional layers by considering the population composition by age in Dong, Eup and Myeon of each region. After allocating the number of Dong, Eup and Myeon in proportion to the number of enumeration districts of the population in each layer, 200 Dong, Eup and Myeon were selected in total. By reflecting characteristics of the selected Dong, Eup and Myeon by housing types, enumeration districts were extracted one by one and 23 households were done from one enumeration district through systematic sampling10.

The survey was conducted in four enumeration districts every week or in 200 enumeration districts every year. The eligible subjects of KNHANES were persons aged over one year. Spirometry was performed for the subjects aged over 19 years.

Spirometry was conducted with Dry Rolling-seal spirometry (Vmax series Sensor Medics 2130; Sensor Medics, Anaheim, CA, USA) by specially trained technicians who conformed to pulmonary function test (PFT) guideline of American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society11. We used the prediction equation derived from the KNHANES II12.

The results of spirometry in each enumeration districts were transmitted to the central quality control center through the Internet to investigate whether the results satisfied acceptability and reproducibility criteria of spirometry for quality control and quality assurance. The results finally confirmed by the principal investigator were stored in the data management system of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC).

Trained interviewers administered questionnaire about COPD at the time of spirometry. The questionnaire included questions about whether to have history of COPD, whether to be diagnosed by a physician, whether to be currently treated and whether to utilize currently medical service10.

As KNHANES IV did not contain bronchodilator testing, the prevalence of COPD was calculated with prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC). The participants aged over 40 years recording less than 0.7 of FEV1/FVC were defined to have COPD. The severity of COPD was determined with GOLD classification13. For analysis on results of spirometry, only results showing two or more acceptable curves and meeting reproducibility criteria were used11.

1) Smoking status: Non-smokers and smokers were defined as persons having smoked less than 100 and 100 or more than 100 cigarettes in a lifetime, respectively. Out of the smokers, persons smoking and not doing at the time of the survey were done as current smokers and former smokers, respectively.

2) Residence and income level: Persons in Eup and Myeon as enumeration districts were considered to live in rural area and those in Dong were done in urban area. Income level was divided based on equivalent income (=monthly income/√No. of familymembers) by revising monthly income per household with the number of family members. In addition, because the income level was largely different by gender and age, the income level was classified in a participant's own gender and age group. The equivalent income by gender and age of less than lower 25% and three upper 25% were defined as 'low', 'low-middle', 'middle-high' and 'high', respectively in the order.

Statistical analysis was performed with SURVEY PROCEDURE of SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) reflecting sample design and weight. The prevalence of COPD and relevant risk factors were analyzed with SURVEYFREQ Procedure and SURVEYLOGISTIC Procedure, respectively. The weight of spirometry was attached only to the data satisfying the suitability and the reproducibility criteria of spirometry and it was calculated by considering sampling rate, response rate and population structure.

Among subjects aged over one year around the nation, 23,632 participated in KNHANES IV. The participants aged over 40 years were 11,628 and they consisted of 4,936 males and 6,692 females. Out of the participants aged over 40 years, 90.5% (10,523) took spirometry. Of these 10,523 subjects, 6,934 (65.9%) satisfied the acceptability and reproducibility criteria. Among them satisfying the conditions of the test, 22.6%, 21.7% and 55.7% were current smokers, former smokers and non-smokers, respectively. For males the current smokers, former smokers and non-smokers accounted for 41.2%, 41.9% and 16.9% and for females they did for 5.5%, 3.0% and 91.4%, respectively.

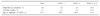

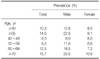

The prevalence of COPD in KNHANES IV was 12.9% (male, 18.7%; female, 7.5%; Table 1). The prevalence of the elderly aged over 65 years recorded 28.6% (male 46.6%, female 16.3%) and the prevalence became higher at older age by recording 4.3%, 10.1%, 19.9% and 32.0% in the participants in their 40s, 50s, 60s and 70s, respectively (Figure 1). A total 96.5% of subjects diagnosed with COPD were found to have relatively mild disease with GOLD stage 1 and 2 (Figure 2).

Only 2.5% of the participants found to have COPD had been diagnosed by physicians. Even in subjects with GOLD stage 3 and 4 only 15.0% had been diagnosed by physician (Table 2).

According to univariate analysis on risk factors of COPD, old age, male, residence of rural area (Eup and Myeon) and history of smoking increased the risk of COPD while the income level of 'high' and higher educational status decreased it. Multivariate analysis with these variables revealed that male, old age and history of smoking were risk factors of COPD and higher educational status declined its risk. However, income level was not related with its risk (Table 3).

The prevalence of COPD of adults aged over 40 years recorded 12.9% in KNHANES IV. It differed from that of KNHANES II which was 17.2%. The discrepancy between KNHANES II and IV was considered to be caused by different criteria of spirometry rather than actual difference in the prevalence. While KNHANES II utilized the results of spirometry showing two or more acceptable curves to calculate the prevalence, KNHANES IV used the reproducibility criteria in addition to acceptable criteria. When the prevalence of COPD was calculated by applying the criteria of KNHANES II using the data in the second year of KNHANES IV it recorded 17.7%14 so that the prevalence of COPD was not significantly different between KNHANES II and IV.

In KNHANES IV, the prevalence of COPD of males was two times higher than that of females by recording 18.7% and 7.5%, respectively and the prevalence became higher at older age. In addition, the prevalence of smokers was higher than that of non-smokers. Multivariate analysis found that male, old age and history of smoking were statistically significant risk factors of COPD. Although low income level had been observed to be an independent risk factor in KNHANES II, it was not related with COPD in KNHANES IV. Instead, the subjects with higher educational background showed a lower risk of COPD than those with lower one.

Despite relatively high prevalence of COPD, its diagnosis rate is very low15 and even patients actually treated for COPD do not know their diagnosis name accurately in many cases16. This study also revealed that only 2.5% of the subjects with COPD were diagnosed as COPD. Even in subjects with GOLD 3 and 4, only 15.0% had been diagnosed by physicians and only 75.6% (N=6) out of them were currently treated. So, efforts to raise the awareness of COPD are needed in the future.

Although many treatments for COPD such as smoking cessation, medication, pulmonary rehabilitation and oxygen therapy have been utilized, there has been no medication slowing the rate of declining pulmonary function or reducing the mortality rate up to now. However, recent large-scale researches have reported that some medications can decrease the rate of declining of lung function and the mortality rate17-19 in patients with moderate COPD, so that the importance of early detection of and proper treatments for COPD has been increased. This study found that 60.5% and 36.0% of the patients diagnosed as COPD recorded GOLD stage 1 and 2, respectively. Only 2.4% of those recording GOLD stage 2 had been diagnosed by physicians and only 1.4% of them were currently treated. For GOLD stage 1, the rates of being diagnosed by physicians and being treated were lower by recording 1.8% and 1.2%, respectively. This finding showed again the importance of early detection and early treatment. Until now a uniform screening test using spirometry for early detection of COPD has not been recommended20, but the necessity of screening test for early detection for subjects with risk factors of COPD has been suggested21. Because KNHANES IV revealed that the diagnosis rate of COPD was very low and its risk factors including history of smoking were determined, this result supported the necessity of screening test for high-risk group of COPD.

Although KNHANES IV minimized seasonal and regional bias by investigating all year around, secured the representativeness of results by attaching the weight through post-hoc adjustment and could obtain more accurate prevalence of COPD by applying stricter acceptability and reproducibility criteria, it had some limitations. First, it did not exclude other diseases associated with airflow obstruction such as bronchiectasis and tuberculous destroyed lung because it did not utilize chest radiography. Second, the existence of airflow obstruction was evaluated with a fixed ratio using FEV1/FVC <0.7, so that the prevalence of the elderly could be overestimated. Moreover, it could not exclude completely the possibility of including asthma and other disease because bronchodilator testing was not conducted.

When COPD was diagnosed with a fixed ratio of FEV1/FVC, the possibility of overestimation among the elderly and underestimation among the young has been raised continuously. To minimize it, lower limit of normal has been recommended13,22. The prevalence of COPD calculated with lower limit of normal was 10.3% (Table 4).

To supplement these limitations, KNHANES V applying stricter spirometry criteria of showing three acceptable curves and meeting reproducibility criteria is in progress. It also includes bronchodilator testing and is planned to use both of a fixed ratio and lower limit of normal to obtain the prevalence of COPD.

In summary, the prevalence of COPD among Korean adults aged over 40 years was 12.9% in KNHANES IV and 96.5% of the participants with COPD were GOLD stage 1 and 2. Most COPD patients had not been diagnosed by physicians and consequently had not been treated appropriately. Early management for subjects with risk factors of COPD is considered to be necessary, and currently ongoing KNHANES V is expected to obtain more accurate prevalence of COPD.

Figures and Tables

Figure 2

Distribution of COPD severity stratified by the GOLD classification. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD: global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We authors sincerely acknowledge the efforts of KNHANES examiners of the Korea Centers for Disease Control who conducted spirometry in enumeration districts.

References

1. Renwick DS, Connolly MJ. Prevalence and treatment of chronic airways obstruction in adults over the age of 45. Thorax. 1996. 51:164–168.

2. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997. 349:1498–1504.

3. World Health Organization (WHO). The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. 2008. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

4. Celli BR, MacNee W. ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004. 23:932–946.

5. World Health Organization (WHO). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Fact sheet No. 315. 2011. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

6. The cause of death statistics [Internet]. Korean Statistical Information Service (KSIS). c2010. cited 2010 Jun 1. Daejeon: KSIS;Available from:http://kosis.kr/abroad/abroad_01List.jsp?parentId=D.

7. Information for chronic diseases 2009. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service (HIRA). c2010. cited 2011 Jun 1. Seoul: HIRA;Available from:http://www.hira.or.kr.

8. Halbert RJ, Natoli JL, Gano A, Badamgarav E, Buist AS, Mannino DM. Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2006. 28:523–532.

9. Kim DS, Kim YS, Jung KS, Chang JH, Lim CM, Lee JH, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: a population-based spirometry survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005. 172:842–847.

10. Korean national health and nutrition examination survey. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC). c2011. cited 2011 Jul 1. Cheongwon: KCDC;Available from:http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/intro/intro01.jsp.

11. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005. 26:319–338.

12. Choi JK, Paek DM, Lee JO. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2005. 58:230–242.

13. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2009. [place unknown]: GOLD.

14. Yoo KH, Kim YS, Sheen SS, Park JH, Hwang YI, Kim SH, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2008. Respirology. 2011. 16:659–665.

15. Soriano JB, Zielinski J, Price D. Screening for and early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2009. 374:721–732.

16. Hwang YI, Kwon OJ, Kim YW, Kim YS, Park YB, Lee MG, et al. Awareness and impact of COPD in Korea: an epidemiologic insight survey. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2011. (accepted).

17. Jenkins CR, Jones PW, Calverley PM, Celli B, Anderson JA, Ferguson GT, et al. Efficacy of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate by GOLD stage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis from the randomised, placebo-controlled TORCH study. Respir Res. 2009. 10:59.

18. Decramer M, Celli B, Kesten S, Lystig T, Mehra S, Tashkin DP, et al. Effect of tiotropium on outcomes in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (UPLIFT): a prespecified subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009. 374:1171–1178.

19. Celli BR, Thomas NE, Anderson JA, Ferguson GT, Jenkins CR, Jones PW, et al. Effect of pharmacotherapy on rate of decline of lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the TORCH study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008. 178:332–338.

20. Lin K, Watkins B, Johnson T, Rodriguez JA, Barton MB. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using spirometry: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008. 148:535–543.

21. Lee SW, Yoo JH, Park MJ, Kim EK, Yoon HI, Kim DK, et al. Early diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2011. 70:293–300.

22. Hwang YI, Kim CH, Kang HR, Shin T, Park SM, Jang SH, et al. Comparison of the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease diagnosed by lower limit of normal and fixed ratio criteria. J Korean Med Sci. 2009. 24:621–626.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download