Abstract

Background

Early recognition and treatment of sepsis would improve patients' outcome. But it is difficult to distinguish between sepsis and non-infectious conditions in the acute phase of clinical deterioration. We studied serum level of procalcitonin (PCT) as a method to diagnose and to evaluate sepsis.

Methods

Between 1 March 2009 and 30 September 2009, 178 patients had their serum PCT tested during their clinical deterioration in the medical intensive care unit. These laboratories were evaluated, on a retrospective basis. We classified their clinical status as non-infection, local infection, sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock. Then, we compared their clinical status with level of PCT.

Results

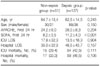

The number of clinical status is as follows: 18 non-infection, 33 local infection, 39 sepsis, 26 severe sepsis, and 62 septic shock patients. PCT level of non-septic group (non-infection and local infection) and septic group (sepsis, severe sepsis, septic shock) was 0.36±0.57 ng/mL and 18.09±36.53 ng/mL (p<0.001), respectively. Area under the curve for diagnosis of sepsis using cut-off value of PCT >0.5 ng/mL was 0.841 (p<0.001). Level of PCT as clinical status was statistically different between severe sepsis and septic shock (*severe sepsis; 4.53±6.15 ng/mL, *septic shock 34.26±47.10 ng/mL, *p<0.001).

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Mean values±SD of PCT in patients with non-infection (n=18), local infection (n=33), sepsis (n=39), severe sepsis (n=26), septic shock (n=62) at their clinical deterioration (1st ICU day). *p<0.001. SD: standard deviation; PCT: procalcitonin. |

| Figure 2Diagnostic performance of procalcitonin for diagnosis of sepsis. Using cut-off value of procalcitonin >0.5 ng/mL for diagnosis of sepsis, area under curve (AUC) is 0.841 (95% confidence interval, 0.776~0.907, p<0.001). ROC: receiver operating charateristic; PCT: procalcitonin. |

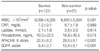

| Figure 3Serum PCT measurment, APACHE IIscore and SOFA score as a predictor of short-term (28 days) mortality in critically ill patients: area under ROC-AUC with 95% CI and p-value (PCT 0.583: 95% CI, 0.495~0.671; p=0.074; APACHE 0.673: 95% CI, 0.589~0.756; p<0.001; SOFA 0.703: 95% CI, 0.619~0.787; p<0.001). PCT: procalcitonin; APACHE: acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; SOFA: sequential organ failure assessment; ROC: receiver operating curve; AUC: area under curve; CI: confidence interval. |

References

1. Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M, Hwang T, Davis CS, Wenzel RP. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. JAMA. 1995. 273:117–123.

2. Hong SK, Hong SB, Lim CM, Koh Y. The characteristics and prognostic factors of severe sepsis in patients who were admitted to a medical intensive care unit of a tertiary hospital. Korean J Crit Care Med. 2009. 24:28–32.

3. Vincent JL, Bihari D. Sepsis, severe sepsis or sepsis syndrome: need for clarification. Intensive Care Med. 1992. 18:255–257.

4. Assicot M, Gendrel D, Carsin H, Raymond J, Guilbaud J, Bohuon C. High serum procalcitonin concentrations in patients with sepsis and infection. Lancet. 1993. 341:515–518.

5. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992. 20:864–874.

6. Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985. 13:818–829.

7. Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996. 22:707–710.

8. Becker KL, Nylén ES, White JC, Müller B, Snider RH Jr. Clinical review 167: Procalcitonin and the calcitonin gene family of peptides in inflammation, infection, and sepsis: a journey from calcitonin back to its precursors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004. 89:1512–1525.

9. Meisner M, Müller V, Khakpour Z, Toegel E, Redl H. Induction of procalcitonin and proinflammatory cytokines in an anhepatic baboon endotoxin shock model. Shock. 2003. 19:187–190.

10. Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Biomarkers in respiratory tract infections: diagnostic guides to antibiotic prescription, prognostic markers and mediators. Eur Respir J. 2007. 30:556–573.

11. Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Procalcitonin in bacterial infections--hype, hope, more or less? Swiss Med Wkly. 2005. 135:451–460.

12. Herzum I, Renz H. Inflammatory markers in SIRS, sepsis and septic shock. Curr Med Chem. 2008. 15:581–587.

13. Rau BM, Kemppainen EA, Gumbs AA, Büchler MW, Wegscheider K, Bassi C, et al. Early assessment of pancreatic infections and overall prognosis in severe acute pancreatitis by procalcitonin (PCT): a prospective international multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2007. 245:745–754.

14. Whang KT, Steinwald PM, White JC, Nylen ES, Snider RH, Simon GL, et al. Serum calcitonin precursors in sepsis and systemic inflammation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998. 83:3296–3301.

15. Nakamura A, Wada H, Ikejiri M, Hatada T, Sakurai H, Matsushima Y, et al. Efficacy of procalcitonin in the early diagnosis of bacterial infections in a critical care unit. Shock. 2009. 31:586–591.

16. Sandri MT, Passerini R, Leon ME, Peccatori FA, Zorzino L, Salvatici M, et al. Procalcitonin as a useful marker of infection in hemato-oncological patients with fever. Anticancer Res. 2008. 28:3061–3065.

17. Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, Gencay MM, Huber PR, Tamm M, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet. 2004. 363:600–607.

18. Stocker M, Fontana M, El Helou S, Wegscheider K, Berger TM. Use of procalcitonin-guided decision-making to shorten antibiotic therapy in suspected neonatal early-onset sepsis: prospective randomized intervention trial. Neonatology. 2010. 97:165–174.

19. Meng FS, Su L, Tang YQ, Wen Q, Liu YS, Liu ZF. Serum procalcitonin at the time of admission to the ICU as a predictor of short-term mortality. Clin Biochem. 2009. 42:1025–1031.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download