Abstract

Progressive ptosis and headache developed in a 50-year-old woman with non-small cell lung cancer. Although brain magnetic resonance imaging showed improved cerebellar metastasis after prior radiotherapy without any other abnormality, the follow-up examination taken 6 months later revealed metastasis to the cavernous sinus. The diagnosis of metastasis to the cavernous sinus is often difficult because it is a very rare manifestation of lung cancer, and symptoms can occur prior to developing a radiologically detectable lesion. Therefore, when a strong clinical suspicion of cavernous sinus metastasis exists, thorough neurologic examination and serial brain imaging should be followed up to avoid overlooking the lesion.

Cavernous sinus syndrome (also called parasellar syndrome) usually presenting with unilateral, progressive painful ophthalmoplegia is caused by disruption of the cranial nerves of the parasellar region. The etiology of cavernous sinus syndrome is difficult to find and diverse including bacterial or fungal infections, non-infectious inflammation, vascular lesions, and neoplasms1. It is relatively rare that metastasis to the parasellar region or cavernous sinus from distant site occur in patients with systemic cancer2,3. In patients with cavernous sinus metastasis, the most common primary sites (sites other than the head and neck) are the breast, prostate, and lung4,5. Herein, we report a case of cavernous sinus metastasis with diagnostic difficulty due to the lack of detectable lesion on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) taken on the time of symptoms.

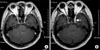

A 50-year-old woman was admitted for evaluation of newly developed ptosis (Figure 1) and headache. She had undergone surgery for lung adenocarcinoma 3 years prior to admission. Her disease was proven to be advanced stage (T4N2M0) because pleural seeding was found during operation. Six cycles of palliative chemotherapy with paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and cisplatin (60 mg/m2) was given. Right cerebellar metastasis developed almost one year after completion of chemotherapy. Radiotherapy of 3,000 cGy to the whole brain and additional 1,000 cGy to the cerebellum was done. Six months later, she complained of progressive headache and ptosis on the left eye suggestive of third cranial nerve palsy. However, brain MRI showed partial improvement of the previous cerebellar lesion without any newly developed lesions (Figure 2) and repeated CSF studies revealed no abnormalities. We decided to observe her symptoms on an outpatient basis owing to the lack of any diagnostic clue to the cause. Headache and ptosis deteriorated over a period of 6 months. Follow-up MRI revealed a 15×12×7 mm enhancing nodule in the left cavernous sinus which was not detectable on previous brain imaging (Figure 3). After the final diagnosis of cavernous sinus metastasis was made, radiosurgery with cyberknife was done leading to slight improvement of her symptoms. However, leptomeningeal seeding proven by CSF cytology accompanied by drowsy mentality developed 4 months later. Finally, she succumbed to death despite intrathecal chemotherapy and supportive care.

Although it is well documented that various types of malignancies metastasize to the parasellar region or cavernous sinus, this metastasis is rarely encountered in clinical practice. Sometimes diagnosis can be challenging, especially when there is no definite abnormality detectable on imaging studies as shown in our case. The rarity of this manifestation in lung cancer patients may also contribute to the difficulty of proper diagnosis.

A pair of intercommunicating venous channels called cavernous sinus is located on either side of the sella turcica. They connect anteriorly to the superior and inferior orbital veins and drain posteriorly into the superior and inferior petrosal sinuses which eventually drain into the sigmoid sinus and internal jugular vein. It is important because of its contents which include the venous plexus, internal carotid artery, periarterial sympathetic nerve fibers, fibrous tissue and cranial nerves III (oculomotor nerve), IV (trochlear nerve), V1 (ophthalmic nerve), V2 (maxillary nerve), and VI (abducens nerve)1. The oculomotor, trochlear, ophthalmic and maxillary nerves are running superoinferiorly in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus and the abducens nerve passes more medially. Even a small lesion can produce multiple cranial nerve palsies6. Among them, the oculomotor and abducens nerves are most frequently involved, followed by the trochlear nerve7,8. Diplopia, ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, decreased corneal reflex, dysesthesias, hypesthesia, headache, retroorbital pain and facial pain are commonly presenting symptoms3.

Many etiologies such as bacterial or fungal infections, non-infectious inflammation, vascular lesions, and neoplasms is associated with cavernous sinus syndrome1. Among them, tumors in the cavernous sinus area may be primary intracranial neoplasm (e.g., meningioma, pituitary adenoma, craniopharyngioma, sarcoma, chondroma, multiple myeloma, lymphoma), or metastatic tumors, either from close primary tumors (e.g., nasopharyngeal carcinoma, cylindroma) or from distant tumors (breast tumor, prostatic tumor, lung tumor, intestinal tumor, kidney tumor, uterine tumor, testicular tumor, bone tumor, melanoma, indeterminate)2,4,5. Table 1 summarized metastatic diseases from distant site causing cavernous sinus syndrome.

The differential diagnosis of ptosis in lung cancer should include Horner's syndrome, leptomeningeal seeding, cavernous sinus metastasis, trauma, hemorrhage, infection, vasculitis, venovascular hypertension and thrombosis9.

The diagnosis of metastasis to cavernous sinus may be difficult if radiologic finding is lacking10,11. Recently, MRI has become the most useful diagnostic tool when evaluating a suspected cavernous sinus neoplasm12,13. However, in suspected cases, repetition of imaging studies may be necessary because symptoms and signs can precede detectable changes of the cavernous sinus on diagnostic imaging10,13,14. The necessity of biopsy is unclear, especially in patients with known systemic cancer with image-confirmed cavernous sinus lesions15.

The management of cavernous sinus metastasis is palliative5,15. Generally, radiation therapy is performed as standard treatment and often leads to improvement of symptoms and alleviation of pain13. However, the prognosis is very poor and the median survival is reported to be 4~4.5 months from the onset of symptoms3,5. Therefore, lack of radiologic abnormalities should not be taken as evidence for the absence of metastatic lesions and treatment should be started under a clinical diagnosis because local treatment such as radiotherapy may relieve or alleviate the symptoms completely11,16.

When a strong clinical suspicion of cavernous sinus metastasis exists, thorough neurologic examination and serial brain imaging should be followed up to avoid overlooking the lesion and treatment should be started immediately under a clinical diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

Ptosis in the left eye. Drooping of left eyelid developed in a patient with non-small cell lung cancer 6 months after radiotherapy for cerebellar metastasis.

Figure 2

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showing cerebellar metastasis. (A) T1-weighted MRI of brain showed a large mass on right cerebellum (arrow). (B) The size of mass decreased 6 months after radiotherapy (arrow).

References

1. Lee JH, Lee HK, Park JK, Choi CG, Suh DC. Cavernous sinus syndrome: clinical features and differential diagnosis with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003. 181:583–590.

2. Bitoh S, Hasegawa H, Ohtsuki H, Obashi J, Kobayashi Y. Parasellar metastases: four autopsied cases. Surg Neurol. 1985. 23:41–48.

3. Oneç B, Oksüzoğlu B, Hatipoğlu HG, Oneç K, Azak A, Zengin N. Cavernous sinus syndrome caused by metastatic colon carcinoma. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2007. 6:593–596.

4. Thomas JE, Yoss RE. The parasellar syndrome: problems in determining etiology. Mayo Clin Proc. 1970. 45:617–623.

5. Spell DW, Gervais DS Jr, Ellis JK, Vial RH. Cavernous sinus syndrome due to metastatic renal cell carcinoma. South Med J. 1998. 91:576–579.

6. Hui AC, Wong WS, Wong KS. Cavernous sinus syndrome secondary to tuberculous meningitis. Eur Neurol. 2002. 47:125–126.

7. Lin CC, Tsai JJ. Relationship between the number of involved cranial nerves and the percentage of lesions located in the cavernous sinus. Eur Neurol. 2003. 49:98–102.

8. Keane JR. Cavernous sinus syndrome. Analysis of 151 cases. Arch Neurol. 1996. 53:967–971.

9. Finsterer J. Ptosis: causes, presentation, and management. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2003. 27:193–204.

10. Greenberg HS, Deck MD, Vikram B, Chu FC, Posner JB. Metastasis to the base of the skull: clinical findings in 43 patients. Neurology. 1981. 31:530–537.

11. Vikram B, Chu FC. Radiation therapy for metastases to the base of the skull. Radiology. 1979. 130:465–468.

12. Yap YC, Sharma V, Rees J, Kosmin A. Cavernous sinus syndrome secondary to metastasis from small cell lung carcinoma. Ann Ophthalmol (Skokie). 2007. 39:166–169.

13. Laigle-Donadey F, Taillibert S, Martin-Duverneuil N, Hildebrand J, Delattre JY. Skull-base metastases. J Neurooncol. 2005. 75:63–69.

14. Ebert S, Pilgram SM, Bähr M, Kermer P. Bilateral ophthalmoplegia due to symmetric cavernous sinus metastasis from gastric adenocarcinoma. J Neurol Sci. 2009. 279:106–108.

15. Panigrahi M, Arun P. Rajasekhar V, Bhattacharyya KB, editors. Uncommon cavernous sinus lesions: a review. Progress in clinical neurosciences, vol. 22. 2007. Delhi: Byword Books;237–247.

16. Post MJ, Mendez DR, Kline LB, Acker JD, Glaser JS. Metastatic disease to the cavernous sinus: clinical syndrome and CT diagnosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985. 9:115–120.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download