Abstract

Background

Procalcitonin is a well known marker in infection that plays a role in distinguishing between bacterial and viral infections in screening. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the role of procalcitonin in differentiating between 2009 H1N1 influenza pneumonia and community acquired pneumonia of bacterial origin, or mixed bacterial origin and 2009 H1N1 influenza infection.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was performed over the 6-month winter period during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Ninety-six patient-subjects were enrolled, all of whom had been diagnosed with community acquired pneumonia in emergency department during the study period. On admission, laboratory studies were performed, which included 2009 H1N1 influenza real-time polymerase chain reaction of nasal secretions and procalcitonin on serum; the laboratory values were compared between the study groups. Receiver operating characteristic curve analyses were performed on the resulting data.

Results

Compared to those with bacterial or mixed infections (n=62) and bacterial pneumonia with confirmed organisms (n=30), patients with 2009 H1N1 pneumonia (n=34) were significantly more likely to have low procalcitonin levels (p=0.008, 0.001). Using cutoff of value >0.3 ng/mL, the sensitivity and specificity of procalcitonin for detection of patients with confirmed bacterial pneumonia were 76.2% and 60.6%, respectively. A significant difference in procalcitonin was found between 2009 H1N1 pneumonia and pneumonia caused by mixed influenza viral and bacterial infections (0.15 [0.05~0.84] vs. 10.3 [0.05~22.87] ng/mL, p=0.045).

Figures and Tables

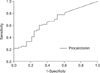

| Figure 1Receiver-operating characteristics curve for discriminating between 2009 H1N1 pneumonia and bacterial/mixed community acquired pneumonia for procalcitonin. Cutoff of >0.3 ng/mL for procalciton best identified patients with bacterial/mixed pneumonia (sensitivity 61.9%, specificity 60.6%, positive predictive value 75.0%, negative predictive value 45.5%). |

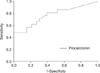

| Figure 2Receiver-operating characteristics curve for discriminating between 2009 H1N1 pneumonia and microorganism confirmed bacterial community acquired pneumonia for procalcitonin. Cutoff of >0.3 ng/mL for procalciton best identified patients with microorganism confirmed bacterial pneumonia (sensitivity 76.2%, specificity 60.6%, positive predictive value 55.2%, negative predictive value 80.0%). |

| Figure 3Box plot of procalcitonin levels between 2009 H1N1 pneumonia and bacterial pneumonia with confirmed organisms. |

References

1. Perez-Padilla R, de la Rosa-Zamboni D, Ponce de Leon S, Hernandez M, Quiñones-Falconi F, Bautista E, et al. Pneumonia and respiratory failure from swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2009. 361:680–689.

2. Global alert and response: pandemic (H1N1) 2009: update 87. World Health Organization [Internet]. c2010. [cited 2010 Feb 18. Available from:

http://www.who.int/csr/don/2010_02_12/en/index.html.

3. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Bridges CB, Cox NJ, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004. 292:1333–1340.

4. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, Brammer L, Cox N, Anderson LJ, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. JAMA. 2003. 289:179–186.

5. Brundage JF, Shanks GD. Deaths from bacterial pneumonia during 1918-19 influenza pandemic. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008. 14:1193–1199.

6. Assicot M, Gendrel D, Carsin H, Raymond J, Guilbaud J, Bohuon C. High serum procalcitonin concentrations in patients with sepsis and infection. Lancet. 1993. 341:515–518.

7. Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, Gencay MM, Huber PR, Tamm M, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet. 2004. 363:600–607.

8. Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, Leuppi J, Miedinger D, Müller C, et al. Antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-guidance with standard therapy. Chest. 2007. 131:9–19.

9. Ingram PR, Inglis T, Moxon D, Speers D. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein in severe 2009 H1N1 influenza infection. Intensive Care Med. 2010. 36:528–532.

10. Harbarth S, Holeckova K, Froidevaux C, Pittet D, Ricou B, Grau GE, et al. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001. 164:396–402.

11. Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Biomarkers in respiratory tract infections: diagnostic guides to antibiotic prescription, prognostic markers and mediators. Eur Respir J. 2007. 30:556–573.

12. Christ-Crain M, Stolz D, Bingisser R, Müller C, Miedinger D, Huber PR, et al. Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006. 174:84–93.

13. Gérard Y, Hober D, Assicot M, Alfandari S, Ajana F, Bourez JM, et al. Procalcitonin as a marker of bacterial sepsis in patients infected with HIV-1. J Infect. 1997. 35:41–46.

14. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Grecka P, Poulakou G, Anargyrou K, Katsilambros N, Giamarellou H. Assessment of procalcitonin as a diagnostic marker of underlying infection in patients with febrile neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis. 2001. 32:1718–1725.

15. Hedlund J, Hansson LO. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels in community-acquired pneumonia: correlation with etiology and prognosis. Infection. 2000. 28:68–73.

16. Moulin F, Raymond J, Lorrot M, Marc E, Coste J, Iniguez JL, et al. Procalcitonin in children admitted to hospital with community acquired pneumonia. Arch Dis Child. 2001. 84:332–336.

17. Chirouze C, Schuhmacher H, Rabaud C, Gil H, Khayat N, Estavoyer JM, et al. Low serum procalcitonin level accurately predicts the absence of bacteremia in adult patients with acute fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2002. 35:156–161.

18. Chua AP, Lee KH. Procalcitonin in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J Infect. 2004. 48:303–306.

19. Brunkhorst FM, Heinz U, Forycki ZF. Kinetics of procalcitonin in iatrogenic sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1998. 24:888–889.

20. Nijsten MW, Olinga P, The TH, de Vries EG, Koops HS, Groothuis GM, et al. Procalcitonin behaves as a fast responding acute phase protein in vivo and in vitro. Crit Care Med. 2000. 28:458–461.

21. Toikka P, Irjala K, Juvén T, Virkki R, Mertsola J, Leinonen M, et al. Serum procalcitonin, C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 for distinguishing bacterial and viral pneumonia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000. 19:598–602.

22. Wright PF, Kirkland KB, Modlin JF. When to consider the use of antibiotics in the treatment of 2009 H1N1 influenza-associated pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2009. 361:e112.

23. Boussekey N, Leroy O, Alfandari S, Devos P, Georges H, Guery B. Procalcitonin kinetics in the prognosis of severe community-acquired pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2006. 32:469–472.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download